The rural Midwest, foreign policy, and the ways we do history

My argument is that the farmers are ultimately the ones driving a lot of this policy and that everyone else is is catching up.

Michael Lansing:The power of place continues even as we bring new ways of seeing and new ways of thinking to the kind of work that we do as scholars collectively in this world of history.

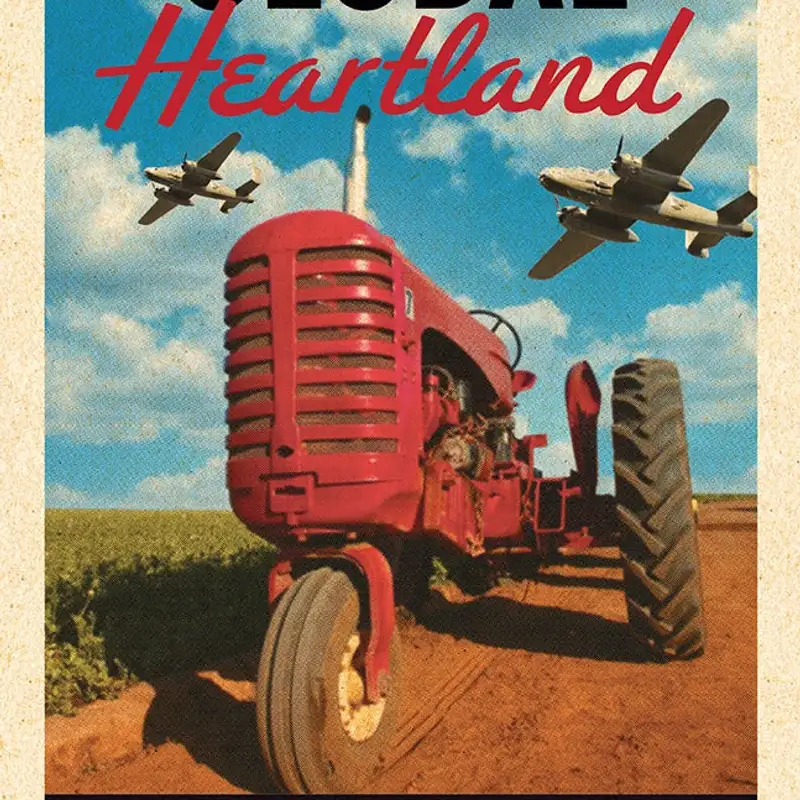

Peter Simons:Hi. My name is Peter Simons, I am the author of Global Heartland: Cultivating the American Century on the Midwestern Farm. It is a book that aims to explain how farmers in the Midwest embraced a global role, after World War II. It explores the transitions both to the practice of farming but also their imagination of their responsibilities to the world and helps explain how entrenched American agriculture has become by the present day. It is something that is to be found globally still.

Peter Simons:It is still an influential force around the world. And I am so delighted to have Michael Lansing joining me today to talk through this book. I have to acknowledge that his book was very influential to me in understanding an earlier era that leads into this transition. So I couldn't have a better person to help think through this book and and talk through what its implications are. Thank you so much, Michael.

Michael Lansing:Well, thank you, Peter. Michael Lansing, professor of history at Augsburg University, and it's a delight to be here with Peter and to talk about this new and really innovative book, Global Heartland. I'm super excited because of the ways in which Peter has put together stories that are, frankly, generally not told. And, also, the book brings ways of seeing that I think really reveals a great deal, things that both historians have not known but also Midwesterners have not known about themselves. And I even found the book to have some explanatory power, for some of my own family's stories, so I'll be anxious to talk with Peter about that, of course.

Michael Lansing:But more importantly, I think Global Heartland is a book that's going to really appeal to people who try to understand, not just the rural Midwest but American foreign policy, especially at these critical moments, World War two and the emergence of the Cold War. And the book just does this incredible job of rethinking, and retelling and reorienting, the way that we see and how we should think about that critical period in the late nineteen thirties, the nineteen forties, and into the early nineteen fifties. So, Peter, it's an absolute delight to be here with you, and congratulations on the book.

Peter Simons:Thank you so much, Michael. I really appreciate it.

Michael Lansing:So I guess my first question for you is, how how did you become interested in this subject? You know, Midwestern farmers in the middle of the twentieth century doesn't necessarily, kind of jump out at people right away when they're casting about for the subject of a book. And a book, of course, like this is anywhere from six to ten years. It's it's it's such a commitment of time and energy. How how did you get interested in this subject and these people?

Peter Simons:I have to admit the the very typical historian's tale of the the autobiography that's pretty deeply embedded into the story, least at least as a jumping off point. And so I grew up in an agricultural community, actually a small city that had a manufacturer that depended on the surrounding countryside and it was sold off to a series of different Swiss multinational corporations. Immediately there was this connection between this community that felt sort of closed off from the rest of the world, obviously wasn't, right? Very much what was happening in Basel was having an effect on this little town that I lived in. The fortunes of the small town sort of rose and declined depending on what was happening elsewhere.

Peter Simons:So, there was that always embedded in that. I was not from an agricultural family. So, I was always looking from the outside, trying to understand this life, the kids that I went to school with, the the, the people that were driving their tractors down Main Street to bring their grain to the the co op so it could get shipped off somewhere. So so that was a very important part of it. I also had the germ of this idea not too long after the war in Iraq began.

Peter Simons:And so there was enormous support for that in the community I grew up in. And so again, was trying to piece together these people who otherwise at least superficially don't have much interest in the rest of the world. Why are they so interested in supporting this overseas adventure? What explains their own foreign policy? And the final critical part of it, I didn't think about this until just just a few days ago.

Peter Simons:I realized that this project all came together in the first period of time that I lived, for a prolonged period outside of the Midwest. It enabled me to think about the people that I was writing about with a clear head, I think, than I had before, that I wasn't embedded in that in it. I think it was really the first time that I thought of Midwesternness in a way that I hadn't really before. And so there's all this autobiographical thing. There's there's that moment of US military adventure overseas trying to make sense of that moment, but then also tracing that back to this earlier story.

Peter Simons:It really started as as a pretty traditional political history. Arthur Vandenberg was the first person who helped me narrate this because he so clearly articulated I had embraced this particular political position. Pearl Harbor made that impossible for me to understand. It was such a simplistic, it was such an enticing explanation that I knew couldn't be true, from the face of it. But he allowed for me to sort of sink my teeth into this one particular story and then unravel that and understand all the different strands of of what his constituents were initially thinking about as they ostensibly followed him to this new pathway.

Michael Lansing:This comes as no surprise, of course, because I think there are a lot of historians who, whether it's through autobiographical experience or just trying to understand this basic question of how rural Midwesterners who seemed on the surface to be, you know, whatever we want to call it, progressive in the first half of the twentieth century, how they come around by the end of the American century and and seem to be so politically conservative. That's a question that's driving, you know, a lot of the historiography, for my generation, for your generation. And of course, it's because we are coming of age in the early two thousands just as you described. So it's so great to hear that. I'm also really curious about this entry point that you found.

Michael Lansing:When did you find that entry point? Obviously, it was when you leave the region that you start to think about it. That's also so classic. Right? And you get kind of clear eyed and you're like, oh, oh, and you start, you know, seeing seeing things differently.

Michael Lansing:But, you know, that entry point of Vandenberg, is that something that you encountered as an undergraduate, as a graduate student? Like, where at what moment for you did that become the entry point, this Vandenberg story?

Peter Simons:It was in graduate school. I have to admit that I don't really know how I came across that. You know, it was I think Hank Meyer was already starting to write articles that would lead to his book that recently came out on on Arthur Vandenberg. That's such a great question, and and I'm not exactly sure how I found that. I promise to not make this all autobiographical, but another element of it is I had decided to enter graduate school because after graduating, as an undergraduate, I went into policy school and I was myself convinced that I was going to go into the foreign service.

Peter Simons:I guess that was the moment I discovered why I really wanted to be historian because the answers in policy school were so simplistic and they were so neat. There was so rarely an excavation of understanding the causes behind particular forces. And so naturally, was was the place to go. And so I think Arthur Vandenberg, probably because of that policy school, he was he was sort of floating in my head. I think there was some attention that was coming back to him because of the book.

Peter Simons:They built a a statue to him in Grand Rapids, Michigan that that now stands. There was a a rediscovery of republican foreign policy near the the beginning of of the twenty first century. So I I think that had to have some cause, but it's sort of a it's sort of an immaculate conception now that you're saying it. I don't I don't know how Arthur Vandenberg found me or vice versa how I found Arthur Vandenberg. So that's something that I'll need to I'll need to think about more.

Michael Lansing:Well, I'm just asking because, of course, I think people always wanna know how the book came to be, like the process of the book. And so I love that you lay out that entry point for us. Where did things go from there? Because your commitment to complication clearly was, you know, a driving force for you as you just described. So you encounter that first kind of set of narratives, and then you keep pushing.

Michael Lansing:You keep moving. Tell us more about that.

Peter Simons:It initially was a story that was so heavily quantitative. I was going through voting roles at the most microscopic level that I could. And then I discovered the tranche of early opinion poll surveys and the disaggregated data and started manipulating the tables to figure out how I could mine all of that information for really finer level detail. And then at some point, the realization that data isn't terribly reliable in the first place, because it really was just from the dawn of public opinion polling. So some corrections needed to be made.

Peter Simons:Then again, I think there was a realization that there's just this, I think, overly simplistic explanation when we're looking at voting data to understand people's drives, why they're making the particular choices that they are. And so following that, there were a number of mentors along the way who I don't know if they introduced me to these subfields of history, but they made them very engaging to me. And so one of the first was historian Nathan Godfrey at the University of Maine. He works on mass culture, particularly mass media and the left. And radio became really enticing to me.

Peter Simons:Way that is explained that, especially for rural listeners, this sort of this transformational, effect that the radio can have on listeners. And so that led me away from this heavily quantitative focus to begin to explore a richer qualitative explanation for why people were beginning to think differently about their own work, the landscapes they lived in, about their own relationship to the rest of the world. And then I took my first course in historical geography. That was the most transformational moment in gaining a deeper understanding for the environmental context that someone is in, the concept of place of understanding where one's positioned in the world and how you relate to everything else. And this ultimately led me to environmental history.

Peter Simons:It was a long road and I think the attraction ultimately to environmental history is it was something that was able to take all of these what seemed like disparate threads and really tie them together. There was room for this political explanation, but also an understanding of place and of physical context of working in the landscape, of a materiality. In a way there's an intellectual history that's part of the story, but there's also a materiality that drives that. And I was admittedly a latecomer to environmental history. I knew it existed, but I hadn't really read deeply in it.

Peter Simons:It really became profoundly influential in how I put these things together and how I was explaining the transformation in viewpoint, in political behavior, in a sense of responsibility that these Midwestern farmers that I write about, what they underwent over the course of World War two and and in the postwar period.

Michael Lansing:Yeah. It's fascinating to me to hear having read the book, it's fascinating for me to hear that you actually started with this quantitative orientation and looking at voting patterns because the book, of course, is profoundly different from that. And frankly, I think much more interesting for the very reasons that you described as you try to recover this sense of place, but not just how this sense of place is created, but how the sense of place then reshapes what actually happens, how it shapes the agency of these rural Midwesterners, as they interact with a host of other folks. And so I'm also struck by the ways in which you just talked about historical geography as an entry point, not just in to rethinking the project but into environmental history. I think you're not alone there.

Michael Lansing:I had a similar experience when I was in grad school. I, you know, had the opportunity to encounter cultural and historical geography and it was it was it was a reorientation that has been fruit ful. Even it even if it doesn't manifest itself, in in, say, everything a scholar does, it's sitting there and it just shapes the way you think. It also makes me think about there's a little kind of mini boom, I think. In books by historians who think about place and take place seriously as a category of analysis.

Michael Lansing:Obviously, Kristin Hoganson's book about the heartland, but I'm also thinking about Molly Rosen's book on Northern Grasslands Memoirs and Settler Memoirs and Sense of Place or Flannery Burke's forthcoming book on how westerners imagine the East. The power of place continues even as we bring new ways of seeing and new ways of thinking to the kind of work that we do as scholars collectively in this world of history. So at the end of the day, what kind of history is Global Heartland? Because you've already pointed us towards two or three different things going on. Tell us more about what you think Global Heartland is as a history.

Peter Simons:It's ultimately an environmental history, I think, but I don't think it's an environmental history that looks like most of what we see. Crops are important, and I talk about the landscape. But you know, there's not like a particular part of the country that I'm looking at how it was transformed because of a particular human process. And I'm not looking necessarily at how The United States is transforming landscapes overseas. There's not a particular biological agent that's doing a lot of work in this case.

Peter Simons:And so it's an environmental history insofar as I'm trying to link an understanding of political ideology, of culture, and how the landscape shapes that without sort of falling back into sort of a mechanistic understanding that a lot of the sources that I referenced throughout the book did fall back on that. A lot of USDA officials that make assumptions that people who live in a particular place have particular opinions about the world that they, you know, they they literally have their their blinders on because they're just looking at the the ground in front of them and can't understand the rest of the world or or you know, a particular crop that they're growing makes them see the world in a particular way. So, you know, don't wanna I wanna fall back into that sort of relationship but there is something I think, fundamental to understanding the environmental context that ultimately leads us to these other things. And this is, I think, ultimately what environmental history at its best is that it's not just explaining, what we might think of as the natural environment, but it's using the natural environment to more richly understand this bigger thing we call history in the first place.

Peter Simons:Taking all these different ways of understanding the past and knitting them together. Sometimes it doesn't always work elegantly, but I hope what I've done here does bring these different strands together, even if I'm saying that it leans heavily on environmental history. There are times where I want to engage in sort of a history of cartography. There's plenty of times where I want to do an analysis of particular messages that are coming through the radio or particular images that that farmers are reading in their farm newspapers and how that helps them reimagine the world too but ultimately, it all comes back to their position in the soil, their relationship, their livelihood, and how it's based in the natural environment. Feel comfortable calling it environmental history, but again, it remains a vexing question to me.

Peter Simons:It doesn't feel like it always neatly lines up with what we might think of as a traditional environmental history. I'll just add to this as I'm thinking again about origin stories. I was very firmly implanted in the world of foreign relations when it began. Similarly, it never quite fit when I would go to conferences or present papers. It made sense to people there, but it always felt like it belonged to a different subfield.

Peter Simons:So you bounce around all these subfields until you find one that feels the most comfortable. Think again, environmental history is that place, but it took a while to navigate and find exactly where the home of this particular history was.

Michael Lansing:Well, this comes as no surprise either because I think Global Heartland, as I read it, is a book that really methodologically is about intersections. Right? Like, obviously, if you look at the notes, like, it's so clear, this immersion in the history of, you know, American foreign policy. Simultaneously, immersion in, kind of farm politics, historiography, this immersion in agricultural history, this immersion in all these different kind of literature. So it's it's yeah.

Michael Lansing:It's no surprise that the project led you in these different directions but it was difficult to find a place that felt like home professionally where you could have conversations with other scholars. I actually think that's one of the reasons the book is so rich and why it's actually a book that lots of different audiences are gonna, find interesting because if you're a historian of foreign policy, there's a very different story here. If you're a historian of the Midwest, there's a different story here. If you're an ag historian, there's a different story here. And so the richness of working at that intersection even though it makes it difficult to write produces a book that's so useful to so many different people.

Michael Lansing:I also think the way that you just define environmental history is, you know, environmental history in its broadest form and, you know, there are are struggles in that field right now and I and I love that you're putting your marker down and saying, I think this is an environmental history and let me tell you why because as you just suggested, there are folks that won't think of this as an environmental history when they open it up and start reading it, but of course it is if you see environmental history in these broader ways. So I love that you're kind of laying claim to that. So let's let's dig into the book itself. Let's let's talk about some of the some of the ways in which you reveal, new understandings in Global Heartland that make us think differently about a whole host of things. The most obvious question that I think people picking up the book or looking at the website seeing, oh, great new book, Global Heartland.

Michael Lansing:What do mid century Midwestern farmers have to do with geopolitics?

Peter Simons:This is the key. And as I read, I was initially dismayed because you read the classics like William Appleman Williams, and he's making an argument that farmers in a way are shaping policy at the end of the nineteenth century, right? That they're always looking for markets. So I thought, well, maybe there's not a story. It's already been told.

Peter Simons:And what I came to realize as I moved from say the policy level down to the behaviors of individual farmers and how they understood the world was that they were not just following what people in Washington were prescribing for them. That they were actually active participants in reimagining what their relationship to the rest of the world was. And so certainly there is a moment in which they are pushed along. So obviously depression, two depressions for farmers that precede World War II, and then the farmers in a way are active in the war before most other Americans because of the Lend Lease Act, which takes American grown foodstuffs and sends it to the American allies, so to the British, to to the Soviets, and and to a number of of different, countries eventually as well. And it it does that through a market mechanism.

Peter Simons:So it's it's not that the farmers are necessarily setting something aside to go to this thing called fund leases. They don't have any choice. If they're if they're producing, they're, you know, some small portion of what they're producing is for lend lease. And so they get pulled into this and it's an economic boom because they've been searching for markets, of course, during the Great Depression. They've been curtailing their production because the USDA is telling them to, and then suddenly they're reversing course and it seems like boom times are back.

Peter Simons:But they're wary. They know that wars end and in their experience that depression follows the war. Don't want to get overly excited that the war is going to be the thing that solves economic depression that they're suffering through. But in the process of producing for war, they do adopt a patriotic outlook in part because they need to explain why what they're doing exempts them from actually needing to go and serve in The Pacific, go overseas and serve as well. So part of it is taking on this sense of an importance of agriculture to the war effort that they are soldiers in the fields.

Peter Simons:Attached to this is an understanding of even like very specific foods and the importance that they have. So butter, for example, becomes the most requested food item for the Soviets. And this causes an outcry that American GIs are not receiving butter, at least enough butter in their training camps in The United States that they're starting to get Southern produced margarine. There's this crisis that you can imagine in a place like Wisconsin or Minnesota of who deserves to get this. These debates help sharpen a sense of the work that's being done on these farms is not just contributing in the abstract to the war, but very specifically, the butter that I produce that has this particular label is being found in a mess hall in England.

Peter Simons:And so I know that I'm making this contribution. And so different from that late nineteenth century description of farmers pursuing markets abroad, is this sense of responsibility and that grows when the war ends. There's a sense among farmers of famine, and a worsening food situation that the war ending is not as good of a thing as it initially seems because Americans are beginning to pull back. The federal government in The United States really wants to have nothing to do with rebuilding America initially. There's a quote from the USDA that they want the last I'm going get this a little bit wrong, but it's essentially that they want the last slice of bread to go to the last soldier who fires the last bullet in the last battle of the war and then nothing be left over.

Peter Simons:There's such a fear that there's going to be, this excess that that that will lead to the depression. So while the federal government is is is pushing back saying we need to end our adventure overseas, pull back home, we wanna end price support, farmers, of course, a bit self interestedly, are wanting to preserve those markets, but there's also something else. Obviously it depends on each individual, whether there's maybe a religious motive, if there's sort of nationalistic motive. Think there's a bit of an environmental chauvinism that this is the breadbasket of the world and we can produce for all of these people. We were the ones who helped win the war ultimately.

Peter Simons:We're the ones who can help prevent a further war by feeding, all of these victims who are left over, mostly in Europe but in other places as well after the war. And so this entwining of economic well-being but also responsibility, a sense of global leadership all come together in the post war period. And there are domestic efforts to push the federal government to embrace rehabilitation, to embrace rebuilding Europe, feeding Europe. It takes many years. And then, the Marshall Plan, is established because there's a recognition that Europe in particular needs to be rebuilt.

Peter Simons:Agriculture is is key to this and so again, there's this sort of insurance that's built in that if the federal government is buying your crops and sending them overseas that that that it's not as volatile as if it were just going out into the market. And progressively, agriculture gets locked into foreign policy that what is initiated as part of the Marshall Plan becomes all of these different programs. Today, most of them exist through USAID that these these farmers in many of the same places that I'm talking about are still sending their grain abroad through these development programs. And so the key here is understanding that these weren't programs that were placed upon farmers, but that they were really key in helping create them at a moment in which the federal government, the USDA, the State Department really showed very little interest in prolonging any sort of presence in Europe after World War II.

Michael Lansing:So how does this story, as you've just described it, scramble kind of more typical understandings of Midwestern farmers as so called isolationists, as non interventionists because the story that you just laid out challenges the basic premises of most people's assumptions about what's going on in the rural Midwest in the nineteen thirties and nineteen forties, in terms of how these farming people, regardless of their ethnic or religious or racial identity, how they're thinking about their relationship with the world around them. How did you how did you navigate that? How did you push back against the whole framing of of these farmers are, you know, totally committed to neutrality? These farmers are totally committed to this notion of, you know, provincialism, the ways in which they're cast by some of their contemporaries, especially outside the region, as you know. How did you navigate that and try to tell this very different story that makes us see so differently?

Peter Simons:That's a really great question. I feel like there were moments where I felt like I had slipped into writing a history as though it were 1953, and I was trying to explain these questions that were prominent at the time about isolationism and they had a moment, I think a few years ago, where they were being answered again. So right, this goes back to Vandenberg who just announces that isolationism ends for any realist because of Pearl Harbor, but of course it's not that simple. As Kristin Hoganson shows, these farmers had deep commitments to overseas markets to biological agents beyond American borders long before World War II. But there is a transformation that happens, several transformations that happen because of the war.

Peter Simons:One is there's a push for efficiency. If part of the goal of the USDA during the New Deal was to take less productive farmers and move them to cities or move them to manufacturing or at least move them to more productive land, the threat of getting drafted and fighting was a far better instrument to do that, that you had to demonstrate to your local board that you could produce so many bushels or that you had so many heads of cattle on your farm. And so what you do is you, first off, have farmers that are producing far more efficiently. They have access to equipment that they didn't necessarily have before. Increasing the size of their acreage and working that acreage with far fewer people.

Peter Simons:And so these farms get larger and they are looking for markets that they didn't necessarily need to have before because there's vastly greater production. But another really important transformation this is an old story for wheat farmers of course because wheat had been moving around the globe for a long time, but because of technologies of wartime, dairy farmers in particular find that their products can now be shipped around the world because dehydration, creating evaporated milk, and all these different ways of taking fluid milk and turning them into products that both soldiers and civilians, can consume overseas. And of course, because of the advances in nutritional science, there's a reframing milk as the perfect food, right? So when you're rebuilding Europe, milk has to be one of the things that goes to the people there. And so I'd be curious in your own reflection on this too, we want to paint with really broad strokes that if you compare a wheat farmer to a dairy farmer, the politics of a dairy farmer tend to be a bit more conservative, they tend to be a bit wealthier, their organizations tend to be friendlier to more conservative politicians, where it wasn't necessarily true that wheat farmers tended to have more liberal politics.

Peter Simons:In those more liberal organizations, tended to find more wheat farmers than ours. So there's that transformation of who can be involved in trade that transforms it as well. Because of the efficiency that I mentioned a moment ago, there's also a new population of people who are coming to work on a lot of these farms And some of them are coming from Mexico for the first time. Some of them are coming from The Caribbean and even prisoners of war from Italy and Germany as well. And even though these are mostly people who are working in in small numbers, of course in the case of POWs, it's for a more limited period of time, it further helps underscore the global networks that it's not just that they're raising goods that are being sent abroad, but the inputs are global as well.

Peter Simons:There's a sense that the seeds you're

Michael Lansing:growing

Peter Simons:had overseas origins, but the very people that you need to work your land to help produce these things are coming from overseas as well. So there's this transformation in the actual work of farming. But then I think there's a transformation, another important one in the sort of ideology of overseas commitment. And so you mentioned a few moments ago, there's almost like this sort of hopeful history when we look at the teens and the 20s that there are these movements in the Prairie that feel a little out of place, that have a vision for society, for politics, that in some cases is utopian, but in some cases maybe just more focused on equity. And the National Farmers Union is one of the organizations that I look at that didn't necessarily have that identity a few years before, but they become sort of the liberal stronghold.

Peter Simons:They're friendly with Henry Wallace when he's in the USDA. And they very much have a cooperative vision that they might be environmental chauvinists, but that leads them to want to share their goods, share their technology, share what they know. It it sort of resembles a brief moment after the atomic bombs are dropped where there's an actual discussion of do we share this technology with the rest of the world? Because we're actually safer if everybody has atomic knowledge rather than just The United States. Of course, this this idea is quickly dispensed with and it's decided that the Americans will have the monopoly.

Peter Simons:And I think this ultimately happens with agriculture as well, that there's this brief moment at the end of World War II where there's a cooperative vision, there's the heady moment of the United Nations being founded, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, but ultimately all of that becomes advisory committees. The Food and Agriculture Organization really just becomes a statistics organization, that they're just calculating how much food is being calculated, how many calories are being consumed around the world. It's not really focused on trying to create a balance of access to food as it was maybe originally. And so that vision of the National Farmers Union is sort of cooperative, you could even say internationalist vision. I don't think they ever necessarily wanted to cede American power to something that was truly balanced among all of its allies, but but it was something that more resembled that.

Peter Simons:That quickly gives way to a fully nationalist one, that The United States would be globally engaged, but it would be in charge. And this maps onto the National Farmers Union really falling out of favor when Truman becomes president, and the American Farm Bureau is numerically larger to begin with, but they re establish themselves as the most important political player. And so once the American Farm Bureau embraces foreign policy as a mechanism to ensure the well-being of their constituents, that helps make that part of American farm policy and foreign policy at the same time. This is something that I I try to trace out in the latter half of of the book of that that transition moment from a more cooperative optimistic moment to one in which US Agriculture becomes an instrument of power, overseas.

Michael Lansing:Yep. That is, of course, how global heartland ends with that turn that you just described. And it's why this book is so important because I think we have a book like Kristen Hoganson's book on the heartland, as you say, which kind of sets sets up your book and then there's been this gap. The in the nineteen forties, there have been this gap and then, of course, we have Shane Hamilton's work on supermarkets and cold war food power. But but the end of your book, the end of global heartland also made me think about Katherine McNicholstock's book, Nuclear Country, and what happens on the Northern Plains in terms of politics and political economy to to turn these into very conservative places.

Michael Lansing:And and what you're showing is that anti communist turn and how the Farm Bureau overtakes the farmers union in those spaces. It's really exciting because it's suddenly you're you're making these connections across time, and it and it has really significant explanatory power the way you end the book. It's yet another reason people should, check this book out. I have to say that chapter three is my favorite chapter and you alluded to it briefly there But your analysis of what's happening back on the farm during wartime, whether we're talking about the draft and deferments or we're talking about the arrival or the, encouragement of workers from elsewhere, the changes in gender or the challenges to the ways in which some of these farmers imagine gender or farm families imagine gender. It's such a it's such a rich chapter, and I have to admit that it had explanatory power for me.

Michael Lansing:My grandfather was a wheat farmer in North Dakota's Red River Valley. He was the oldest son of immigrants and he had a deferment, an agricultural deferment. I remember talking to him and, you know, like when you're a teenager and you're kind of a history nerd and you're coming of age and it's like, oh, wow, wow. You know, grandpa and grandma were around during World War II. Wow.

Michael Lansing:So, you know, so you started asking them, the elders, these questions and it was kind of a dead end to the mind of this, you know, 14 year old boy. Like, oh, you had you you didn't you didn't go to war. Well, you know, his his younger brother, you know, was on bomber cruise in the Pacific, but he had this agricultural deferment. And and when I was reading chapter three, I was like, oh, not only did I love the gender stuff, but I loved the way that you talk about how farmers are navigating what this challenge means and their own very complicated feelings about patriotism and nationalism and the need to make money to stay on the farm. And it just resonated so powerfully, with the experiences in my own family.

Michael Lansing:It was really great to see that and and the ways in which chapter three, of course, is also the heart of the book. It's it's it's how you put it's how you put farmers at the center in this narrative, I I think as a reader at least. And so when you put the farmers at the center of these stories, how does that look differently? I mean, most historians have looked at the policymakers or they've had that William Applman Williams kind of view from way up here. Even some of the books I just mentioned have that kind of, you know, 20,000 foot view.

Michael Lansing:But you bring us right down on the ground and what it's like in these rural communities. How does that change that history in your mind?

Peter Simons:That that's such a good question, and and and I really appreciate your your comment about the deferment. And what comes with that is reading so many cases of guilt where farmers are able to express that they have this important role to play, that they are soldiers in the field. But at the same time, is this feeling that I'm not standing in harm's way and that, am I really making the same sacrifice? And so there's a very brief story in that chapter about a farmer, a farm son who feels that ridicule. His mother talks about how when he's walking to church, everyone is sort of glaring at him.

Peter Simons:So he enlists. And I think it's at Iwo Jima that he ultimately dies after that enlistment. That is part of the story, is understanding how they are relating to possibilities of what their options are. It helps us understand what sense they made of the world. They weren't just reacting to, again, to really basic market inputs that they're just gonna produce something and it goes off into sort of a black box and they get money for that.

Peter Simons:That there is an understanding behind the role that they play, a sense of responsibility, a sense of maybe national pride or even something more international, something cooperative that gives them a stake in politics ultimately. They a feeling that they are remaking the world at the end of this. And so there's another part of a subsequent chapter in which once the United Nations is established, there's this competition for where the United Nations is going to be. And I didn't find any evidence of farmers per se who were submitting, possible locations but there were lots of of other rural Midwestern sites that were, proposed as ideal locations for the United Nations. I think this is another example of in understanding what the farmers are thinking, their obligations, we get a sense of how they are ultimately helping shape the foreign policy that comes to be the American century.

Peter Simons:That's really a key piece of it, that they aren't just contributing to the American century by producing for it, but they are expressing their vocal support for it, that they understand they have a responsibility, that this is a way to preserve global order to prevent a third world war. And that in many cases, it's their representatives who are late to arrive at that same conclusion. They do see the merit in sending food aid abroad, but it takes them until 1950 to to eventually get there. My argument is that the farmers are ultimately the ones driving a lot of this policy and that everyone else is catching up on. And again, they have myriad reasons for arriving at that particular conclusion.

Peter Simons:And, this is this is one of the biggest complications. I mentioned the variation between wheat farmers and dairy farmers a moment ago, but of course you add all these different crops and you add the different geographies of where these particular crops are growing and of course the faith backgrounds that they might be coming from or ethnic groups. Obviously there's a lot of complication in how people are understanding their relationship to relatives who are back in Germany or the role that, I don't know, growing apples has compared to growing wheat or something like that. And so part of that richness helps us understand the different motivations that all of these different people that are getting ultimately grouped together as Midwestern Farmers writ large, all the competing interests that they have and ultimately pushing The United States toward embracing this global responsibility, this position of leadership, or you might say a position of hegemony at the end of World War II.

Michael Lansing:Yeah. Absolutely. And again, thinking about farmers as innovators, is something that for twenty first century readers is is it seems so foreign, and it's part of the power of Global Heartland is that you reclaim that agency and say that actually they're ahead of their elected representatives. You can't just go to the political opinion polls. You can't just look at voting records, as you noted.

Michael Lansing:You can't go to those places that might seem like, oh, well, this is what's going on. These complications, they matter so much. With that in mind and because the book sits at these intersections, I mean, there's wide ranging research here. When you look at the when you look through the notes, as a reader, you can see like you you kinda have to go all over the place, just to recapture and reclaim these complications. Did did you have a favorite primary source that emerged, while you were doing the years of research for this book?

Michael Lansing:Was there something that just like popped for you or a primary source that you read and you were like, oh my gosh, that's it, where you had this kind of crystallization? Or was it a more gradual kind of accumulative experience that you had when you were working, especially with the primary sources?

Peter Simons:There is such an at times it felt like an overabundance of information because this is coming on the heels of the New Deal. There are all these government agencies that are trying to record opinion and trying to they're commissioning ethnographic studies of particular, rural places. And so there were just so many things to look at that seemed to document everything so richly. But ultimately it had me sort of falling back into that original sort of political history that quite frankly wasn't quite as interesting to me. When I began reading letters from farmers who were stationed overseas, those proved to be, I think, among the richest sources insofar as they offered the position of someone who did that work on the farm but was forced to have a new perspective on it because they were abroad.

Peter Simons:Then there's obviously the pressure of being in harm's way that probably makes them think about their own lives and the relationship to the people they love back home. But they would so often be really deeply contemplative about their work on the farm and whether that's something that they should go back to and whether that was a responsible thing to do. And in one case there was a person called Lester Helen who did go back to a farm at the end of the war in Wisconsin and he really ruminates in the letters back to the woman that would become his wife on what it's like to be in the world and that he doesn't want to be sort of shackled to the farm that he had grown up on, that he wants a different world. Wouldn't it be great to live in the city? But he also happens to be stationed in Puerto Rico when Wendell Willkie arrives on the beginning of his around the world trip.

Peter Simons:And so he has this wonderful insight into how someone who grew up on a farm in the Midwest is looking at the world around him, he's also intersecting with these other global players who will help shape the postwar world. And again, in his case, goes back to the farm. Maybe you say his service was this brief moment, this brief cosmopolitan moment, and then he returns to the farm and becomes sort of a stereotypical Wisconsin farmer. It is one of those moments where you get a sense of who he is, how he sees the world beyond just who he was voting for or what organizations he was a part of. There's just a really beautiful richness and I think a vulnerability that a lot of those historical characters are expressing in those And so I think that probably is among my favorite sources, although there were so many really interesting visual sources as well.

Peter Simons:Instances where manufacturers of agricultural goods would adopt, for example, global imagery. It always felt just a little bit too on the nose, but it was of course what I wanted to find that there is this transformation that we're not just talking about growing corn in Illinois anymore. We're talking about growing corn for the entire world. There is a responsibility come that comes out of that. So so I think both of those, the the the sources that really give that that personal sense of individuals, but then there's some just really beautiful, visual sources as well that that help tell the story.

Michael Lansing:And one of the best parts of the book is when you go through those letters of these, you know, people in the service abroad writing home, thinking and reflecting. It's such powerful source material. And as you say, it kind of gives you perspective. It gives you a window into the thinking that other sources can't provide. But where and how did you find those letters?

Michael Lansing:There's not like discrete collections out there. You don't go to such and such archive and look in that collection and there they all are. How how did you figure out that those were gonna be a rich source and then go looking for them? Because there's they have to be scattered to the winds.

Peter Simons:There were a lot of false starts. There there were a lot of research trips to communities, and I thought this is going to be the core of the book, that I'm going to figure out this particular community and the richness of the sources would help me give a thick description of what the people here experienced during this period of time. And it never really happened. There was just never a place that I found that was able to do that. But in the course of doing that, you do start to pick up on these crumbs of usually just by happenstance, going through all the letters of vets in a particular collection.

Peter Simons:Eventually you find a farmer who shares their experience. So it was a lot of slow going. I don't know what the hit rate was, but it was probably pretty low of like below 10% of how much material you'll find that actually turns out to be useful and how much you're just kind of sifting through to find something. And of course the thing that was so painful is as I was returning to a lot of this material preparing the book for production, so much of it has been digitized now. And so many of the things that I just spent like months reading through, I could just do a keyword search now and it would be over in probably a day.

Peter Simons:Now admittedly, I wouldn't get 1% of the the complexity that I think you get from reading all of that unnecessary stuff because it really helps create this constellation of the worlds that these people are living in. I do appreciate that all that material that that eventually doesn't make it in. The book can exist without that. But it really it really was just a lot of false starts for a long time and then every once in a while you find something that's that's really fantastic and and really helps pull all of the different threads of the book together.

Michael Lansing:This is something that I feel like, as colleagues, we don't talk about enough in the research process, whether we're teaching students or talking about it with each other. A, how much happenstance there is, as you just noted. B, how things are kind of like murky and then they slowly emerge and it's not until you get to the end you're like, oh, that's what happened. And that the the kind of messiness of qualitative processes to the extent that there are processes where you, you know, you do all this work in the secondary literature, you have your questions, you go out, you don't find the sources that you are looking for, you find these other things, how do you make sense of that, all the way to what you just described as, you know, how you had to do all this work that now, of course, digital opportunities make so much easier. But then you wouldn't have all that context if you hadn't, you know, trudged, spent half a day going through all the other letters in that collection.

Michael Lansing:I always tell students that, you know, when we do historical research, what shows up in the article or what shows up in the book is it's like an iceberg. You see 10% of the research in the notes, like when you look at what the colleague did, 10% of it. There's 90% of the research that's not even in the notes, and yet that 10% couldn't be there if that 90% wasn't beneath the surface. So it's no surprise to hear you say that. I I wanna ask a different question.

Michael Lansing:A question that's about, the world that this book is coming into, the scholarly world that this book is coming into because it's it's 2025. The book is coming out in May. It's called Global Heartland. It's about the Upper Midwest at its core and, of course, for the last decade, there's been this very self conscious movement amongst, historians to reclaim a category of analysis, regionalism, but in particular to identify, the Midwest as a space, that some have argued is, you know, understudied and requires, new attention. Of course, there has been a really significant change in that there's now a professional association for people studying Midwestern history.

Michael Lansing:It's often referred to, colloquially as the new Midwestern history. This is the world that your book is coming into, and obviously it's going to become a significant part of those conversations. People ignore this book at their peril, I would argue, because it tells us so many things about the Midwest because you put Midwesterners at the center. But talk to us about how you feel about that, talked about how you position yourself as a scholar in this project, how how you imagine the so called new Midwestern history. I'd love to hear you reflect on that now that you're at the end of the process and that the book is coming out.

Peter Simons:I have to admit that even if I I I don't want it to be, as you suggested, like, the the book inevitably has to be part of that conversation. And I'll admit, I've contributed to, I've written chapters in the edited decisions that are coming out. So am certainly guilty of that. And in a way, I guess we should never say that more history is bad history, Like we should always want to have more of anything to help us more richly understand the past. I do, I mean, as much as I mentioned when I began that it stepping outside the Midwest for a period that you maybe for the first time understand yourself as a Midwesterner, There is this almost of Midwestern chauvinism that I want to avoid.

Peter Simons:And so I guess that's why I'm tentatively saying like I understand that this is a contribution to it and I do want to support these histories because I want support any history that's being written. And it is the Midwestern story that I'm writing and I am trying to make an argument about these people who seem like they aren't part of this world of diplomacy and foreign relations and global politics that they are a part of it. I I struggle in part with with the conception of of a Midwest to begin with, to be honest. And part of that is, again, all the various strains that are coming to play that I sometimes feel that there are people that I'm writing about who are from Nebraska and then someone who is from, for example, the Upper Peninsula Of Michigan that do these people have something in common as it relates to a region? Guess there's a propinquity that they're close to one another, but I don't know that there's a particular explanatory power there of talking about them in that regional context.

Peter Simons:Obviously, if we're thinking about someone like Bill Cronin, when there's these very clear connections of flows of commodities throughout the region and then you think of a great West in that way that there are these ties. But if we don't necessarily have those, I'm uncertain about, I think about the project more generally and, and maybe trying to knit together this sense of Midwesternness is there, if there is this sort of shared culture or geography or politics or economics. These other regional histories like the history of the South, right? Much of the the new Midwestern history is being defined in contrast to these other histories, right? And There's something that makes those other histories make sense.

Peter Simons:Slavery, of course, the South is something that although there might be all of these very disparate cultures, like they were unified because of this phenomenon that existed there. And if we think about New England, it's such a tiny, part of the country that there can be this cohesion that we don't find in the expansiveness of the Midwest. And so I honestly don't know what to take. I would be curious of your own insights. Again, I'm happy to be contributing to this, but I don't know exactly what the contribution is.

Peter Simons:I don't know that I'm, like, helping make the argument of there being a cohesive Midwest that has some sort of historical explanatory power, but I am certainly talking about the people who who live in that particular region. So in that way, am certainly contributing to it.

Michael Lansing:Well, so, you know, I was trained a long time ago, by a number of people who were part of that whole coterie, the new western historians when those debates in the 1990s were late 80s and 1990s were so hot, about what is the American West or North American West and how do we define it? And one of the things that they taught me was that anyone who gets too deep into those debates is probably taking their eye off the ball, ironically. Right? Like, we need we need to have some understanding of our basic categories as we analyze the past, as we think about how to interpret the past, but that any kind of rigidity is deeply problematic. Anytime someone wants to say, here's the definition of say a region, you should you should take it seriously but you should also look at it kind of like, maybe?

Michael Lansing:Are you sure? Like, there are so many other ways to do it. And of course, in the history of the American West, that's been, you know, aridity or like what's a unifying factor whether it's environmental or cultural or any, you know, relationship with the federal government. Like, all these different ideas have been floated. And at some point, you you need to familiarize yourself with those as a historian.

Michael Lansing:You need to be you need to read all that. You need to think about all the different ways the region has been thought of, but you also don't want to let it, like, tie you down. And one of the things about Global Heartland that I so appreciate is that it is. Whether you want it to be or not, it's going be a significant contribution, to the to the new Midwestern history, but it it doesn't but it does so not by trying to lay claim to something about what the Midwest is. It it it's that's not important given the questions that you are asking.

Michael Lansing:You are focused on these rural Midwesterners, these these farmers and, the people in the communities around them, and how are they grappling with these big questions. So by just simply putting these people at the center of the story and trying to explain how they see the world and what they're doing and how they're shaping things, how they're interacting with people, whether it's from The Soviet Union or from the USDA, you're actually doing us more of a service than trying to lay claim to something about some innate Midwesternness. And and I think based on what you've shared here, I think that's in no small part because of your, you know, interest in and training in historical geography because of his historical geographers, of course, have much more complicated ways of imagining region and talking about region. And I see that kind of suffused. As soon as you said that, I lit up because I see that suffused through the book in ways that are, powerful and actually make the book more useful ironically to anyone interested in the history of of that region.

Michael Lansing:Just as, historians of American foreign policy, I think, are gonna find the book really useful.

Peter Simons:No. I I I really appreciate those comments. You're exactly right that the goal there is is not to define the region as as particular thing. I think that's part of my hesitancy that there's a bit of it feels like there's an embedded nostalgia at play in the new Midwestern history and that's something I want to get away from. How you make the argument that it's an understudied region when at the center of it is probably the most studied place on earth, Chicago.

Peter Simons:Have been no other city has as many books and studies that have been written about them as Chicago. And so right, I think the goal there is to complicate it. My fear is that sometimes when we approach the region in that way, it moves us away from the complication and the richness that we need to truly understand it. Yeah, so I appreciate that.

Michael Lansing:Yeah. And I think global heartland is part of this emerging movement within that smaller subfield that is pushing back against the nostalgia that has too often been at the heart of the project as it was defined in the twenty teens. And there are other scholars like you who have these more complicated understandings and envisions and that's another reason the Global Heartland is going to be an important book, and why I think a lot of people are going to find a lot of usefulness in it because, there's a different way of seeing and thinking about the region here and it's it's one that, frankly matters more, including these untold stories like the agricultural deferment story and the context around that that you build in the book. That's just one example of many. So I actually have a a another question for you that is about how the book lands in this moment, and we focused on the question of how it lands in terms of scholarly currents in this moment.

Michael Lansing:But what about 2025 in The United States Of America? What does this history tell us about our own time?

Peter Simons:This particular moment, 2025, it it in a way, feels like a coda potentially of of this story. Right? That it's it's this moment where you have all of these forces coming together to to make The United States a truly global force and a global force that all of its citizens are members of. And USAID, of course, is the organization that was the first to come on the chopping block recently. And I will admit in the way that I write about it, is a critical lens to it that in a way USAID is created as a dumping service for American agricultural goods.

Peter Simons:But at the same time, there's no denying the fact that it was moving calories, was moving nutrition to people around the world who needed it. And so, as a historian, only time will truly tell, but is this the moment where we are truly identifying the end of the American century? That is this moment of hegemony by choice rather than maybe being imposed by another rising power. So it is not the moment that I imagined the book to be coming out in, but it certainly helps put the action that's happening in fine relief and it helps question the environment in which these changes emerge from. It helps give that sense of a complicated isolation.

Peter Simons:Right? That that it's not that The US isn't interested in exerting its power around the world, but it doesn't have that that mid century vision anymore that it seemed to have. Even even though it would it would obviously take on a different complexity with each administration that that would come through it. It always generally had that same tenor. And again, I'll leave it as a question whether whether we are seeing the end of that for something different.

Peter Simons:Is it is it an intermission and then and then we return to that or is there something different that comes after that too? So it does, I think, help really put into relief the story that I'm trying to tell. And again, it serves as as a bit of a coda to that history, I think.

Michael Lansing:I couldn't put it better myself. Peter, thank you so much for this book. Global Heartland, it's a it's a great book. People need to check this book out. They're gonna find all kinds of things that change your mind about what you think you know about the subject.

Michael Lansing:So it's just so appreciated. Congratulations on the publication of Global Heartland.

Peter Simons:Thank you so much, Michael, and and thank you for your really wonderful and incisive questions. I really appreciate the careful eye that you took to the book, and I I appreciate it so much.

Narrator:This has been a University of Minnesota Press production. The book, Global Cultivating the American Century on the Midwestern Farm by Peter Simons is available from University of Minnesota Press. Thank you for listening.