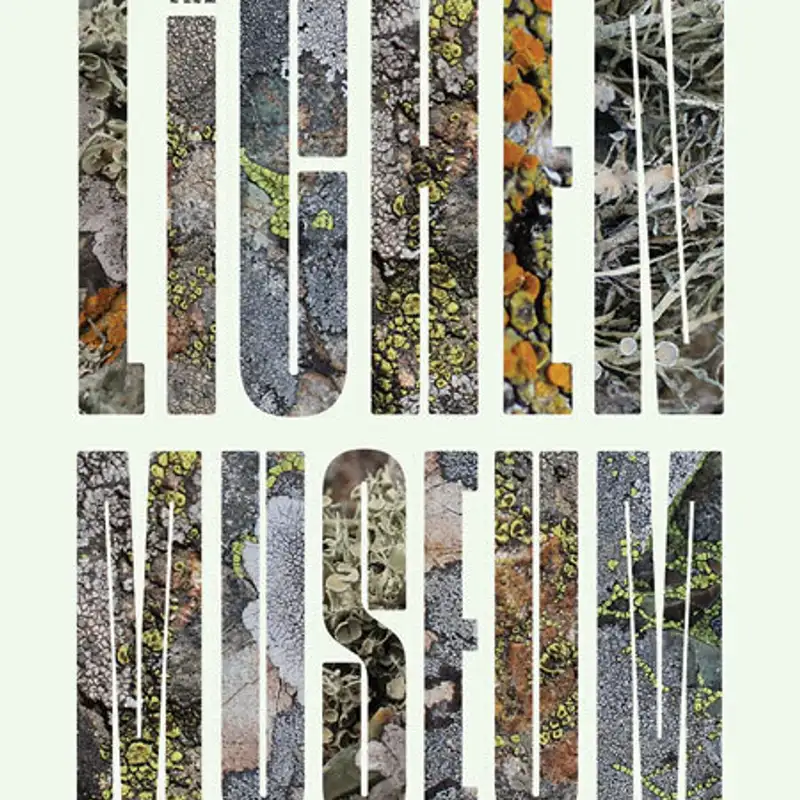

The Lichen Museum with A. Laurie Palmer (Art after Nature 4)

Projects like yours to me can become blueprints and models that show us how we can recover different knowledges.

Caroline Picard:There is no pretense that the natural environment isn't present all the time.

A. Laurie Palmer:They really are doing this unbelievable symbiotic project of creating something that when they're separate is nothing like what it looks like and what it does when they're together.

Giovanni Aloi:Welcome to a new Art After Nature podcast. My name is Giovanni Aloy. I am the co editor of the series with my colleague Caroline Piccard. The series publishes books on nature and the Anthropocene. At a time of unprecedented ecological crisis and cultural change, Art After Nature explores the epistemological questions that emerge from the expanding environmental consciousness of the humanities.

Giovanni Aloi:Authors featured in this series engaged with the recent ontological turn appending anthropocentrism in order to grapple with the dark ecological fluidity of nature cultures. The anthropogenic lenses of inquiry emphasize an ethical focus for grounding the more than human politics of our era.

Caroline Picard:I'm Caroline Piccard. I'm the coeditor with, Giovanni Loy. We're all here with a Lori Palmer on behalf of the fourth book in our series, The Lycan Museum. It's really exciting to be here, obviously, and let me just say a little bit about this book. Serving as both a guide and companion publication to the same name, the Lichen Museum explores how the physiological characteristics of lichens provide a valuable template for reimagining human relations in an age of ecological and social precarity.

Caroline Picard:Channeling between the personal, the scientific, the philosophical, and the poetic, a Lori Palmer employs a cross disciplinary framework that artfully mirrors the collective relations of lichens, imploring us to envision alternative ways of living based on interdependence rather than individualism and competition. Lichens are composite organisms made of fungus and algae or cyanobacteria thriving in a mutually beneficial relationship. The lichen museum looks to these complex organisms remarkable for their symbiosis, diversity, longevity, and adaptability, as models for relations rooted in collaboration and non hierarchical structures. In their resistance to fast paced growth and commodification, lichens also offer possibilities for humans to reconfigure their relationship to time and attention outside the accelerated pace of capitalist accumulation. Bringing together a diverse set of voices, including personal encounters with lichenologists and lichens themselves, Palmer both imagines and embodies a radical new approach to human interconnection.

Caroline Picard:Using this tiny organism as an emblem through which to navigate environmental and social concerns, this book narrows the gap between the human and natural worlds, emphasizing mutual dependence as a necessary means of survival and prosperity. A Lori Palmer is an artist and professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and we are so happy to be here with you. Maybe just to kick things off, I thought it would be really exciting to hear about how this book came to be and what made you start thinking about the lichen museum.

A. Laurie Palmer:Laurie? Thank you, Caroline and Giovanni and Maggie for this talk and also for University of Minnesota to publish this book. Yeah. I'm I'm very grateful to all of you to be here. Like any long term project, I think this one is a convergence of a lot of different desires and experiences over a long period of time.

A. Laurie Palmer:I've think I've been interested like a lot of people in lichens for most of my conscious life, maybe even pre conscious, like being outside in the woods and exploring. I also was interested when I went on a I went on an artist residency in the Arctic, the Arctic Circle residency, and was aware that the one thing growing in that environment was lichens. There are some little tiny trees that grow about six inches tall, but basically that's it. And so I've I've found myself really, really fascinated by looking down in this amazing icy snowy landscape and looking for these things that had really, really long temporalities. So partly I think I I was alerted to look for them because going to the Arctic in, I think it was that was in 2010, I was already thinking about how do we think beyond our own lifetimes?

A. Laurie Palmer:How do we think outside of our limited, you know, human scope? And and I think a lot of people going on these trips to cold places where the the glaciers were melting and all that were thinking along these lines. And it seems like lichens provided this sort of in between time to think with, so they weren't as ancient as as long geological epics and eras that are really mind boggling, but they were in these middle ranges of time between well, some lichens are are shorter term, but many of them are hundreds of years, some thousands, even speculatively, some ten thousand if they are living in Antarctica inside the ice. So so I was really interested that way. And then it started to just snowball all these different ways that brought me back to learning more about the symbiosis, which I know is sort of a poster child for many other ideas about symbiosis, but the lichens are kind of the first in many ways to open that up.

A. Laurie Palmer:And, I started to just see in them so many possibilities. And then I remembered that I had made lichen ink in 1990, and I still had it hanging around. And so there were all these threads that started to tie together.

Caroline Picard:Do you feel like you're like, I guess I'm interested in how your relationship to Lycan, how that might have changed your approach to your own art practice if it did, thinking about modes of presentation, your relationship to institutional space. But then also something that you talk about quite a lot in the book is just kind of like the act of seeing or what it means to be present in relation to seeing. And all of those things seem like they necessarily affect the way you might engage your own work as an artist making. That's why I was interested in I don't know. Just hearing you talk a little bit about that development.

A. Laurie Palmer:Yeah. Those are really, really central questions, Caroline. I think the idea of the Leica Museum as a art project in terms of a frame to see the all the world as a museum that's sort of turned inside out, I think is very much about having had a non object based art practice most of my life. I and, I started as a printmaker, but then got into sculpture and increasingly sculptures that were time based and destroyed themselves or evaporated or whatever. But thinking about the larger world of living and that, certainly played into the work I did collaboratively with the group for twenty years, actually, where we were really focused on experiential space in many ways.

A. Laurie Palmer:I mean, I never really made those connections before until you asked this question exactly, but I think I was really interested in looking away from the established institutions, not to dismiss them altogether, but to play with turning them upside down or inside out. And, actually, Caroline, you offered this amazing opportunity in Chicago in 2015 to stage the Leica Museum as an institution inside another institution. And what we did for that in the gallery you ran in Chicago was to show some some video, but also to direct people outside to the sidewalk where people were pretty quickly down on our hands and knees with our nose to the sidewalk in the middle of, you know, the West Side Of Chicago. And so there was this way of just thinking of museum as not a place that things have to be stilled and killed and preserved, but instead, a museum as the space of living and the space of experiencing and the space of relating. I did travel to, visit several lichenologists before I was thinking about this book, but just as part of thinking about lichens and interviewing them.

A. Laurie Palmer:And in one herbarium in The UK, I think it was in sorry. It was in Northern Ireland. This wonderful paleontologist who is also a lichenologist, you know, led me through these drawers of desiccated little bits of things. And it was really hard to imagine how they could embody what lichens are. And instead, I just was thinking really where the archive should be is out in the world, and that's where I wanna direct people.

A. Laurie Palmer:So in many ways, this book is kind of like a a companion to direct you outside and to to be looking. And that gets back to your other question about the problem of seeing, really, which is historically and the certainly the traditions that I grew up in as a white person in Western culture, but much bigger than that is a uneven balance of power between the human who's, who's looking, turning what they're looking at into an object. So it's a subject object relation. And it's really hard to imagine getting outside of that, but I I'm aware of it as a imbalanced structure of power that is deeply connected to natural history practices even as natural history is wonderful as a way to get people to look at the world and be in the world and to be surprised more than anything. But it's still how do we get outside of that power relation so that our relations with what we are communing with are not happening in this sort of hierarchical ladder of value.

A. Laurie Palmer:And so I think there's so much that is being written and discussed these days that's very revelatory and exciting that tries to make horizontal our relations, you know, in the more than human world that I know your series has everything to do with. So that those structures of power, those uneven structures of power are not being reinforced every time we're an observer. And so I tried to think about looking at lichens because they're so already horizontal most of the time, at least in Logan Square when we were on our knees in the sidewalk, but also because they're so small and they seem to be, in many ways, in those historical ladders of of value from the Greeks on in Western culture at the very bottom. And so what would it mean to commune with with these beings that are already sort of devalued in in many ways, and to imagine them as subjects at the same time, or even to imagine ourselves as objects and objects. So just shifting the imbalance of subject to object.

A. Laurie Palmer:And I don't, you know, pretend that it's something you can just do quickly, but I think it's really interesting as an experiment. And I see the premise of this book in many ways and the project of the Leica Museum as an experiment in thinking and doing and seeing differently. I just wanna say also that I've had some wonderful lichen walks lately since the book came out, which have been really fabulous. And one of them this last weekend was in Santa Cruz at the new Institute for the Arts and Sciences that is currently hosting a series called Visualizing Abolition that they've been working on for several years, actually. And so they invited me to do an abolitionist Lycan walk.

A. Laurie Palmer:And it made so much sense to me because they had perceived, they'd recognized within the book and its content that this is what basically, you know, it's trying to do. Abolition as they understand it in this really broad term and as I do also isn't just about taking down prisons. It's about undermining and taking down all of those structures that are oppressive to, especially, certain peoples over others and to rebuilding other ways of of seeing and doing and being in relation. So I was so grateful for that invitation, and it was amazing. There were 50 people who came to this walk.

A. Laurie Palmer:I've never given a walk with so many people, and I didn't have enough lenses, which was really a shame. But part of the thing about Likensit is maybe this is one of the things that I should have started by answering your question about how did I get there. Is there collectivity? I mean, as a person who's very focused on the potential and the necessity of shared beingness, rather than competitive individualism, I really love the idea that people share the lenses. So maybe that was a good a good part of the whole walk too.

Giovanni Aloi:Laurie, you say so interesting. And this this new relationship between the inside and the outside and also kind of upturning the power structures, The power of the gaze inside and outside made me think of a clip that I play for my students in plants and art class at the School of the Arts Institute of Chicago, which is from the New York Botanic Garden archive. And in the clip, the director of the botanical garden in New York shows different specimens. And at some point, she unfolds a tiny little paper parcel. And inside it, there's a tiny fragment of a lichen that was collected by Darwin.

Giovanni Aloi:And And at that point, my students always laugh because there is this, like, almost ceremonious unfolding of this piece of paper, and she's in a massive archive filled with so many plants. But this one tiny fragment of a lichen that's unrecognizable is the thing that she wants to show. Part of that laughing, I I always question what what's funny about this? After a while, we get to the point that the lichen is the most unlikely organism for the archive. It just doesn't it seems wrong for it to be there because it's perceived as something that is always attached to something else.

Giovanni Aloi:And once you remove it, it can only really come off as a fragment. And once it's a fragment, it no longer is remotely what it was meant to be. While a dried plant might look brown and might look shriveled, it still sort of retains some sort of plantness that makes sense. That lichen seemed to just become a fetishized relic of some kind. You know, the only thing that really seemed to matter is that it was collected by Darwin.

Giovanni Aloi:Otherwise, it's just a little spike of vegetal matter or, like actually, not just vegetal matter, but multi organism matter. And it kind of made me think about what you're saying, you know, the idea of the gaze and opticality and and what is the point of seeing and where different registers of visibility perhaps are more apt to what we can see and what we should see today. So in the context of seeing, I was interested since you throughout the book, you talk about your collaborations and experiences with scientists. I was curious to hear more about your experiences in sort of aligning your gaze with their gaze, and if you could tell us a little bit about that experience.

A. Laurie Palmer:Yeah. That's a that's a really wonderful anecdote and entry point, Giovanni. I did have a similar thing happen in this, herbarium in, Northern Ireland. But what made the connection for the person who was unwrapping these little bits of things were the stories. You know?

A. Laurie Palmer:Who it was who collected them because he happened to know if not know them personally, then he knew of them through like and lore. And so the stories were being unwrapped. It really had very little to do with this fluffy bit of stuff or dusty bit of stuff. And so that was actually one connection, you know, that they were through telling the stories, talking about being outside collecting or about the biography of these people and their relations in a, you know, broader sense to other parts of the world. So it opened up a lot even as the thing itself was was just an excuse kind of at that point.

A. Laurie Palmer:I did have a very specific agenda when I was I learned so much, and I was so surprised and just amazed by whom I got to speak to when I was doing this research and tracking down people. The main agenda that I had to make sure to ask each of them was about how they would describe the relation between the fungus and the algae. Because in my reading about how it was described, it was always a power relation. It was always that the fungus was the master and the algae were the slaves. And there were very many other descriptors, like the fungus were vampires sucking the life out of the algae or the fungus had the algae in sexual slavery of some sort or I mean, it was like a lot of human fantasies projected onto these things, which, of course, I'm doing a certain amount of projection myself in writing this book, but hopefully to undo those particular understandings as if they were naturalized or common sense kinds of relationships.

A. Laurie Palmer:And so I was asking the lichenologist to consider the algae giving themselves into this relation, not being taken or captured or imprisoned. And it made for really interesting conversations. And I didn't have an automatic, I don't wanna talk to you. It was more like, let's talk, but, you know, I don't see it that way. Or even actually, maybe the most generous was, well, that's a narrative.

A. Laurie Palmer:You know? And I said, well, it's also a narrative to say that it that it's this imbalance power relation, and then they would have to admit that. You know? But I have to say, I I gave a talk at the also just in the past couple of months at the Santa Cruz Natural History Museum, and there was a lichenologist in the audience there. And he insisted that those imbalanced power relations are not how US Lichenologists understand it now, which I found to be really hopeful and interesting.

A. Laurie Palmer:Although I have to say it's not exactly been my experience talking to, like, an allergist in The US, but I really respected that he said that and that he saw that change coming. I also think that that particular person was not particularly amenable to the kinds of ways that I was talking about lichens. That too, the crowd was huge. It was really it was standing room only at the Natural History Museum. It was so wonderful, and people were very, very they had wonderful questions.

A. Laurie Palmer:But this one person who was sort of in the field, I really hoped to talk to him, but he kind of scurried away. And I'm trying to reach out because it's not that I feel like we have to agree, but I am very interested in how, as an artist, you know, these ideas can touch, reach, you know, have relations with many different kinds of other professions and perspectives. And it's part of what I wanted I've always wanted to do as an artist is not remain within a a certain bubble of audience, but to be engaged with ideas and practices that could reach a lot of people. And I have to say this is probably the most multi tiered project that has done this because I'm also getting emails from people who are, you know, since the book has come out, who are like an enthusiast, like an artist saying they wanna connect. And it's really great.

A. Laurie Palmer:They're not turned away by the conceptual dimension of the book so far, it seems, most of them, and are instead just glad to meet another enthusiast. And so it's really and also the kids. The kids that come on these walks are are some of the most acute discoverers of of where to see on the tree or the sidewalk.

Giovanni Aloi:Yeah. There is also, I think, a dimension in this context, Laurie, is also the idea that for a while, I always feel a little bit uncomfortable when I call out how science, as in a way, impoverished our world because I'm afraid that sometimes people jump to the conclusion that it's some kind of discounting the validity of science, but it's it's more complicated than that. You know? I think there's a lot of work that we need to do in the West to appreciate how science has created an enormous amount of knowledge. And at the same time, as it is well known, it has purged all other knowledges aside and and discounted their value.

Giovanni Aloi:And I think projects like yours to me can become blueprints and models that show us how we can recover different knowledges and rearrange certain voices. But I think sometimes in my experience, some specialists in their field feel very protective of the conversations, the terminologies, and and the trajectories of narratives that are allowed or not allowed. And, it would probably take time, right, to, break the mold. There is also a a level of feeling uncomfortable, I think, in that arena that is a productive kind of feeling uncomfortable, but it's perhaps not yet for everybody. It takes work.

Giovanni Aloi:So you were talking about time and a certain different perception of time itself. Sometimes I feel that we're all on different time frames when it comes to where we are at with our relationship, with our disciplines, and already we might or might not be to pull down the walls that keep us in that professional space.

A. Laurie Palmer:Yeah. I mean, one of the things about making this book, which sort of came out of the longer project, was wanting to have multiple voices from different disciplines threading through it and carrying some of the conversation in the book itself. I really interested in in writing, but I'm also really interested in in dialogue and having these cross disciplinary conversations. And the grad program that I've been directing and now at UC Santa Cruz environmental art and social practice, it's all about trying to mix these different discourses and or to find where they are useful together. I also am really aware that there's a kind of fear of softening of all all of our, intellectual capacities if we do too much mixing.

A. Laurie Palmer:And I think that that's something that, you know, I am always in terror of also, especially living in California. You know? Northern California. Not to diss Northern California. It's wonderful.

A. Laurie Palmer:Here I am in Mendocino in a cabin in the woods. But it's so it's a fine line, I think, what you're talking about, Giovanni. And, of course, the amazing braiding sweetgrass is such a incredible guide for a kind of way to do that with precision and with grace. And so many people, again, from so many different ages and, you know, positions love that book because it leads a way where science is respected. And in that case, indigenous practices in particular are brought into dialogue and interrelation.

A. Laurie Palmer:But I do think, I mean, actually one of the best things that one of my colleagues said I was so grateful for after speaking at the Natural History Museum in Santa Cruz was she said, it's your talk was so specific. And I really appreciated that because I don't want it to be a blur. I don't want it to be, oh, yeah. We're all, you know, live in one big happy family and should all get along. I mean, on some level, you know, but but I want it to be specific.

A. Laurie Palmer:In fact, there's so much to say about like. But one of the things is just that they really do they really do exist. It's not a fantasy. It's not a total projection. They really are doing this unbelievable symbiotic project of creating something that when they're separate is nothing like what it looks like and what it does when they're together.

A. Laurie Palmer:That in itself is still so amazing. And I know that, you know, there's so many other ways to understand symbiosis and so many examples, but this particular one is about, you know, the transformation that happens when these organisms come together and from different kingdoms. And, again, it's not anymore thought that it's just fungus and algae. It's definitely, you know, several other, you know, whether bacteria or yeast or other organisms that are involved that help to catalyze this amazing symbiosis. And it's a mystery.

A. Laurie Palmer:That's one of the radical qualities of lichens is that even the most intense lichenologists don't know how it works and haven't figured out what the communication mechanisms are that make this transformation. So, I mean, that mystery is valuable in itself as a mystery. I mean, it also invites somebody like me to move into that space of not knowing and to kind of elaborate in it about how lichens can teach us how to be different. But it also really is happening. And I think the fact of lichens is existing in this parallel world to what some humans are doing and that they're doing it so much better and so much so differently is is really, really helpful, I think, in in an otherwise really pretty terrifying time.

Caroline Picard:For some reason, that makes me think about one part of your book also where you describe how maybe impossible it is to determine how long lichen live and then whether or not they die and then how we would think of individuality for lichens. That really stood out to me because everything about those questions seems so counter to the way contemporary societies exist and live. And so and then I also thought it was really interesting how I think having to incorporate that even just like that as a baseline in a book will fundamentally challenge, I think, the way one writes. Because even in writing, I think there's kind of this implicit assumption that there is a death at the end. Like, if you're gonna if you're gonna read a biography, there's a death that will happen.

Caroline Picard:I'd love to hear you talk more about different elements like that about lichens that really stand out as, almost like disruptors to the way we think or the way we might be in the world together.

A. Laurie Palmer:Yeah. That's a really great aspect to pull out, Caroline. I have to try to refer to some of the scientists who I spoke with and also read lichenologists who have explored the specific question of both how do you tell what's an individual and how do you tell if it's dying or not. One of the things about lichens lichens is there's so many exceptions and so many variations. So really, I think that from what I could tell, the the thing that they share is that their habit of collaboration.

A. Laurie Palmer:That it's a habit of being that they share. And in terms of their longevity, I think that some scientists who study certain colonies of lichens have understood that because those colonies do not reproduce sexually, but they reproduce clonally. Lichens have about four different ways of reproduction, which is a wonderful queer dimension of them that is I think other people have really elaborated on. But in this these clonal sort of colonies that that are quite extensive, pieces of the lichen sort of clip off, break off, and form new lichens. But in this scientist's perspective, that meant that the lichen never never dies because it's just pieces of itself continuing to grow and flourish.

A. Laurie Palmer:Maybe other parts of it, like maybe its elbow, you know, shriveled up and died, but the rest of its leg and knee is growing across, you know, in another place. And I don't know what if that metaphor quite works, but but, basically, that that's one aspect of thinking about it. And there's another person who has been studying lichens in Massachusetts in graveyards, and she also has been theorizing that lichens never die a natural death. And as I understand it, part of what happens with human cells and a lot of many other sort of animal cells is that there's something inside ourselves that maybe it's telomere. I don't that might be an old term, but it just, clicks off at some point and the cells die.

A. Laurie Palmer:And that I think certain mycologists, I think, are realizing that maybe some fungi don't have this. I'm really kind of extending beyond my confidence here in terms of expertise, but I know that these are ways in which lichenologists are theorizing that they don't necessarily die a natural death. I would like to actually learn more specifics about this, but that is connected to the question of individual. And, again, if you think about a lichen being formed from fungus and algae basically choosing to to be together, is that already can you say that's an individual? It's already a plural.

A. Laurie Palmer:And then if you think about it in a more expansive sense as that lichen, you know, grows and grows, what are its edges? It depends what kind of lichen it is because there are some lichens that grow from a single kind of foot, fruticose lichens, And so that would be more like an individual in in a sense, but it's already plural. And there and it's often with many other parts of itself nearby. Once you get into lichen reproduction, that opens up this wonderful nonnormative sexuality dimension as well, which kind of opens up, like it's not really I don't know. Is it a marriage when the algae and and fungus get together, or is it something less heterodox?

A. Laurie Palmer:You know? Is it something more about a a kind of unusual living arrangement?

Caroline Picard:That makes me think too about your other book, In the Aura of a Whole, Exploring Sites of Material Exploration and Exploring Sites of Material Extraction. And just like in that book, If My Memory Serves, you sort of have compiled a series of essays that talk about visiting industrial sites of extraction and writing essays about the very granular process of extraction, but also your own, like, subjective observations and biographical associations, I feel like. And so it seems like there is kind of, a parallel writing practice or a sort of strategy for also capturing maybe this interdisciplinary approach. And this is sort of going back also a few steps before in our conversation, but just how that formal kind of weaving in your writing seems to also reflect the non normative presence or strategies of being that are in in the lichens that you're observing. But I don't know if you would agree with that, I guess.

A. Laurie Palmer:I love that way of thinking about it. Yeah. I'm really interested in mixing tones and voices in in writing and bringing in mixing tones and voices in in writing and bringing in personal and scientific and philosophic, in the same space. That is a kind of plurality that I think you're referring to, and I I really appreciate that comment. I may have done even more of that in in the aura of a whole because the scale of that project well, just even literally, I was looking at these massive scale sites, and it just it's sort of interesting to me to move from that project to this one, which is about such small scale kind of relations.

A. Laurie Palmer:And when we go on lichen walks, it's always such a joke because we move about, you know, six feet in an hour and a half. And and and in the aura of a hole, I was traveling all over the country and, unfortunately, using a lot of gas. But I do think that writing for me is, in a way, an art practice. And I I mean, it is an art practice, I guess, I would say. It I have to admit that I I really like words, and I probably in the way that real writers like words too.

A. Laurie Palmer:But I'm interested in how that mix of kind of approaches and voices is really close to art practices that are interdisciplinary and attempting to, going back to another part of our conversation, like you said, bring together many different kinds of ideas into the same space and try to find the connections and make sense of our lives that way.

Giovanni Aloi:That's a really important point too, Laurie, about writing as a legitimate form of art that I hope more and more people will warm up to in the next few years. There is still a strange divide I find between artists and and writers, and, like, I think writing is very much misunderstood oftentimes in terms of creative process. That's at least what I encounter when I talk to my students that are cliches and stereotypes that somehow stick particularly well to the idea of the artist as not being a writer or not using writing as as a medium that I think are still very inconvenient because they're limiting. And there's something about limitations of thinking as well as your desire to blur boundaries and and break down hierarchies that I find particularly interesting in the context of also what I've been researching for a long time, which is this hierarchization of genres in art, the subjects that used to be popular, and desirable during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. So the canon, the hierarchization that sees at the top history, mythology, religion, moving down all the way to, animals, plants, landscape.

Giovanni Aloi:It makes me think, well, lichens are not even there. Right? It's just completely overlooked to the point of irrelevance because, like you said and explained very well, I think that the issue is with subjectivity. You know, in subjectivity, we are hardwired to relate to other subjects or objects. And and once that power relation is jeopardized or become too volatile, we kinda lose interest.

Giovanni Aloi:Especially, I think, lichens in the context of your exploration in the book, sort of short circuit capitalism in a sense that they become difficult to harvest, if not impossible, difficult to trade, if not impossible. And all of these contingencies have kinda made, I think, now, like, and so interesting as you foreground them. There's something I'm interested in, and I think we probably are also nearing the end of our podcast time wise. But I wanted to hear a little bit perhaps about the aesthetics because we've started talking about looking. And one of the things that strikes me about lichens is how enticing they are.

Giovanni Aloi:You know, it's their the colors, the textures, the morphologies, and they always seems to be unique. We've been talking about them as non individuals, but they're also impossible to repeat, you know, the way they form on a specific rock or a stone. So I was kinda thinking about how it's so easy for us to visualize a geranium, for instance, and even, like, a specific species or a variety of geranium, but how it becomes impossible to visualize for all of us a lichen that is very similar, like, in our heads to whatever we're thinking. And and yet that lichen is an individual, but it's so individual that it's also in in its in its kind of plurality is also super individual. I'm thinking about aesthetic questions of representation and and how to kinda negotiate those.

A. Laurie Palmer:That's all very, very interesting. I think you just that's a lot that you packed into that. Just but ending up with aesthetics, I I mean, just the thing it's making me think of is how people just fall in love with the lichens as soon as they are introduced. For instance, going on these walks, some people come because they're really into it, and others have never known what a lichen was. And you give them the lens, and the lens allows them to just dive into a world.

A. Laurie Palmer:I don't know how that really relates to what you're saying about aesthetics and individuals, but I feel like it's a potential way to lose yourself as a human and to enter into this parallel world where you're captured by the aesthetics of these of these things. And what is it that's so aesthetic about them? I think in a very rough way, there's there's some sort of shape and order when you look closely. And I'm talking mostly about these micro lichens, like crustose lichens that you don't necessarily notice until you have the lens or that you that look like a, you know, scab of paint or something, and then you realize it's this whole amazing world. I think that, you know, my response to thinking about the aesthetics is mostly how compelling it is in spite of people.

A. Laurie Palmer:I don't know how to explain that really. Like when people make paintings of lichens or drawings and collate it's it's usually fields. It's not a thing. And that's a really, really important point, actually really interesting, which is back to, again, collectivity and and some of the politics that are, from my perspective, deeply embedded in this project and this book that, you know, are informing it in terms of, belief in how much we need each other and and how much more can happen in terms of more people thriving when we recognize that. And also not just each other, but obviously the the larger world.

A. Laurie Palmer:Some of the nonindividual aspects of lichens is also that they are so permeable to their environment. They are poikilohydric, which means they can't regulate their moisture content. So whatever moisture's in the in the environment comes right into them, which they can use. And if if there's no moisture, they dry up and go dormant. I mean, again, depending on what kind of lichens they are, how much they need to metabolize, but it's a really interesting, intense vulnerability to the environment.

A. Laurie Palmer:But you could also think of it as just, you know, engagement with it and handshaking with it. That as humans, we too are deeply vulnerable and engaged with our environment, but we build all these structures to make us imagine we're not.

Caroline Picard:One of the things that it makes me think about in relation to is this idea of place. And I like, I feel like place is very present in your book also. Like, the presence of Northern California and Northern California at this moment, like, whether it's researchers that are trying to study photosynthesis to discover ways that we can no longer sleep or, you know, essentially, to figure out ways that we might be able to adapt photosynthesis so that humans wouldn't have to sleep so we could be more productive. But then at the same time, there's this presence of, like, wildfires, and then there's this presence of lichen, which is outside. So I thought that was also very powerful to me, like, the placeness of Northern California in the book, basically.

Caroline Picard:It's like the idea of the museum. The museum creates a framework and the place is inside and the artwork is, like, taken from outside and put in this like controlled environment versus like what you're talking about. There is a kind of real porousness between inside and outside. The lichen is everywhere, it's outside. And so I think in some ways also, there's no pretense that the natural environment isn't present all the time, I guess, is what I'm like trying to circle around, which I think is really interesting as an aesthetic position.

A. Laurie Palmer:I wrote the book during the huge part of it during the pandemic when I was held up inside, which is sort of a contradiction. You know? But inside in Northern California, for sure, and I think since I moved here seven, eight years ago, it's certainly hugely, affected me, my poikilohydrism not being able to keep, you know, its influences out. I mean, part of Northern California is its technological, you know, ambitions, and that's part of, I think, part of what you're referring to with the studies in photosynthesis. And sometimes I start talking about lichens with trying to identify five of the most radical qualities.

A. Laurie Palmer:But I didn't do that this time because there's there's really so many more. But one of them that we haven't really gone on about is is slowness. And what I think looking at lichens can do I mean, I mentioned, you know, going on a walk and only moving a few feet in an hour and a half and being absorbed by these worlds, but really trying to think about time in a in a really different, less accelerated, less sped up, more of a body time no matter whose body it is, trying to pay respect to and recognize that our materiality as humans and the the ways that other other beings maybe are more adapted to capable of.

Caroline Picard:Yeah. It makes a lot of sense. I mean, it's such an exciting book. I know I keep saying that, but I feel like receiving it in the mail and seeing it and sort of holding it as a printed bound copy was such a thrill, especially after all of the conversations that we've been having, and such a pleasure to be able to talk to you about it.

A. Laurie Palmer:Thank you. It for for inviting me to to make it. I mean, that was amazing. That was amazing. And it it really you know, in spite of having been thinking about lichens for a long time and, you know, trying to videotape them for years and years and years growing, which is an ongoing project, it's a really, really interesting practice.

A. Laurie Palmer:But writing the book just took me into territory I didn't expect or anticipate. And I really appreciate how that kind of invitation in a way can lead one somewhere. And I am really, really grateful for that, both of you and also to University of Minnesota Press.

Giovanni Aloi:Thank you, Lori. It's Been really great working with you and we're very proud of your book.