Public history, memory, and building a tribal archive.

I really feel the work that was begun with the protocols was really the start of indigenous data sovereignty movement.

Rose Miron:Archival materials are so important for this work. If Native people don't have access to them and if they're being interpreted without Indigenous knowledge, they're not going to create the kind of new narratives that we should be creating.

Rose Miron:There. I'm Rose Miron. I am the Vice President for Research and Education at the Newberry Library in Chicago, and I am the author of the book Indigenous Mohican Interventions in Public History and Memory. I'm really excited to be in conversation today with Jennifer O'Neill, and I think we're both just going to start this recording by saying a little bit about our professional backgrounds and our research interests. So I'll just start out by saying I'm a non native historian.

Rose Miron:I have bachelor's in history and a PhD in American studies from the University of Minnesota. And since finishing my PhD, I have spent the bulk of my professional life at the Newberry Library. But I worked for the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition between graduate school and coming to the Newberry. And that certainly played a big role in how I think about archival collections. And my kind of main role there was thinking about the digital archive that they have now launched and doing a lot of the kind of behind the scenes work on that before it became public.

Rose Miron:I started at the Newberry in 2019 as the director of the Darcy McNichol Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies. And I was in that role for about five and a half years before moving into my current position as the Vice President for Research and Education. My research interests overall are about indigenous history in the Great Lakes in the Northeast, particularly as it relates to public history and memory. And I'm just excited to be in this conversation today about my book and to be in conversation with Jennifer whose work I have really admired for a long time. So I will pass it over to you, Jennifer.

Jennifer O'Neal:Yes, I'm also very excited to be in conversation with you today, Rose. I'm Jennifer O'Neal. I'm an assistant professor in the Department of Indigenous Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of Oregon. And I'm also affiliated faculty with the History Department and Robert D. R.

Jennifer O'Neal:Clark Honors College. I've been here at the University of Oregon for over twelve years. And prior to that, similar to Rose, I've also served in a variety of different capacities. And particularly before being in my current department, I also served as the university historian and archivist here at our university library. And prior to coming back home to Oregon, I also served as the head archivist at the National Museum of the American Indian and worked with some incredible collections there, as well as served as an archivist and historian at the US State Department, as well as served as a lot of other repositories as well as I was going through my education.

Jennifer O'Neal:My area of research is really focused on this interdisciplinary intersection of Native American and international relations history in the twentieth century to the present, with an emphasis on sovereignty, self determination, cultural heritage, global indigenous rights, archival activism, and legal issues. So I'm very much excited to be able to talk about a lot of our overlapping research areas and be able to expand on a lot of the work that we've both been doing in this area of indigenous archival activism. So I'm very excited to be able to talk with Rose today, particularly about her new book. And really what we hope to do today with this conversation is not only for you to hear a lot more about her incredible book and really the experiences that she had in writing this book and being in community with the folks that she worked with, is to really come to know and understand some of the real challenges that tribal communities face when building their own archives and the activism that's involved with that. I'm a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, which is one of the nine federally recognized tribes here in Oregon.

Jennifer O'Neal:I know firsthand a lot of the major challenges that tribal communities face, not only working with my own tribal community, but also in working with tribes across the state. So I'm very excited to be in conversation today. Rose, with large booked projects like this, of course, not only are we seeing the incredible final product, but we know so much goes into doing this work, many years of building partnerships and relationships and even just starting this project in your graduate career. So could you share a little bit with us about how this project first started and particularly how you began to build and relationships with the Stockbridge Muncie community.

Rose Miron:Yeah, absolutely. You know, the development of my relationship with the community is such a big part of the book. So I think it always is a great place to start the conversation. This book actually started as my undergraduate thesis. The University of Minnesota, there is a program that encourages undergrads to work on primary source research with a faculty member.

Rose Miron:And I had the very good fortune of getting to work with Doctor. Jean O'Brien, who is a professor at the University of Minnesota and is a very esteemed scholar within the field of Native American and Indigenous studies. And so I was introduced to this oral history project that the Stockbridge Muncie community was working on at the time. I grew up in Northeastern Wisconsin, but I was pretty largely unfamiliar with the Mohican nation and definitely wasn't aware kind of work that they were doing to reshape their history. And so when I was introduced to this oral history project, which was all about kind of pushing back against that myth that they had disappeared.

Rose Miron:The title of the series was like, we are still here, hear our voices. And so I was really interested in just like that effort to really directly address and attack that disappearance narrative and basically kind of started going to the public airings of the oral history project. And at that point began talking with folks that I was meeting at that event and building my relationship with the Stockbridge Muncie community. And of course, many of the folks who worked in the tribal archive and museum where these videos were being shown were part of the Stockbridge Muncie Historical Committee. And so as I'd be able to continue to kind of come to the library and watch these recordings, they really encouraged me to look at the archives and to look at some of these other materials.

Rose Miron:And that eventually led to me being invited to attend one of the historical committee meetings. And it really just sort of opened this conversation of what I was sort of interested in looking at, but also what they were interested in having written about. At that point, nobody had really written a narrative of the history of the historical committee, of history of how this archive was created. And so my historical committee was really interested in having that story written. And I, of course, became very interested in that as well.

Rose Miron:As soon as I sort of realized that this one oral history project, which is what I wrote my undergraduate thesis about, was really part of this much larger initiative related to the tribal archive. And so together we discussed the idea about me going to graduate school and kind of pursuing this as a dissertation project. And then we really just kind of set up a series of, not necessarily guidelines. We didn't actually sit down and draft them or anything like that. But it was just sort of an iterative process of having a conversation about what is this relationship gonna look like?

Rose Miron:And really making sure that reciprocity was at the center of it. It was really agreed upon at the front of me even applying to graduate school that as I continued to work on this project, I was going to be showing up and coming into the community to not only do research, but to meet with the historical committee and to share my findings with them. As I continued to do that and give updates, the historical committee eventually asked me to conduct some oral interviews. And so that became part of the project. And that led to working with the legal department to really think about, you know, how do these oral interviews get conducted in a way where the tribe retains control over these stories?

Rose Miron:And then I think it, you know, naturally evolved to, okay, like, I'm gonna go out to the East Coast and do some research. How can I help bring more materials back to the archive, the tribal archive that the tribe has not been able to scan yet? So it just sort of developed organically over time in terms of what the needs of the communities were, what I was seeing in the archive, and really just kind of became this reciprocal relationship in which we are both working together to tell this story. And I think that really has continued, you know, into the present and into my current work with the community. I think it was a big part of the book even getting published, you know, as we were going through that conversation and getting explicit permission from tribal council, like making sure that all of the book royalties got set up to go back directly to the tribe and just thinking about like, what do public events for this book look like?

Rose Miron:So I think it's just a, it really just developed into an ongoing collaboration and conversation that has continued to evolve and develop and grow throughout the now fifteen years of this project's life.

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah, that's such an incredible story of just how that partnership and relationship evolved over those many years and how you continue to have that incredible partnership with the community. And of course, anytime you do a huge project like this and focus on Native history and activism, Of course, any project like this is also connected to place and memory. For those people who might not be familiar with the specific history of this community, can you tell us a little bit about why place and memory and particularly where Stockbridge Muncie people are coming from and these different histories and areas that they're trying to gather their records from and the different times they've been removed. And I think it's helpful for people to understand why that's so important to this project and why place is so important to this project.

Rose Miron:Yeah, absolutely. So the homelands of the Stockbridge Munsee Mohican community are on the East Coast of what is now The United States, kind of on either side of the Mahikanatuck River, which is now called the Hudson River. And prior to contact with Europeans, they lived in that area and had relationships, of course, with other tribes across the area. And it was with the arrival of Europeans that, of course, their lives began to shift quite drastically. And so the kind of first initial shift happens in the eighteenth century when they accept a mission in, there in what was an already existing village, called Bonattica, but is now known as Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Rose Miron:And they accepted a mission there with John Sargent. And so people will hear a lot about Stockbridge as a town throughout the book. It comes up a lot just in terms of like where this history is represented on the East Coast. And that's because it's sort of like the first major relationships that are built between European settlers and Stockbridge Munsee folks. And it's where a lot of the kind of initial conversion starts to begin.

Rose Miron:We see that a lot throughout the book. I won't go into like every kind of step of the story, but I will say overall between the late eighteenth century and really into the mid twentieth century, the tribe is removed seven different times. First to Upstate New York, then down into what is now Indiana, and then into Wisconsin, and into various parts of Wisconsin. And it really wasn't until the mid twentieth century that they were able to kind of regain the full reservation that they were promised as part of the treaties that removed them. So, what we see is this series of multiple removals across several centuries.

Rose Miron:And with each of those removals, of course, there are archival materials that are created about the Sacrificance community, whether they're created by tribal members themselves, whether they're created by non native actors who are interacting with them. And so we see that the kind of archival historical record of this community is really scattered across not only Wisconsin where the tribe is based now, but also kind of all across the Southern Great Lakes and then up into the Northeast. And so I think that makes for a very challenging project in terms of recovering one's history and in terms of thinking about how a community starts to go about getting that information back and making it more accessible to their own community members. And so I think that context is extremely important just in thinking about, like, what this initiative looked like for them. I'll also just say that I the, I think a lot of listeners are probably familiar with either the book or the movie, The Last of the Mohicans.

Rose Miron:And so this community in particular has really, really suffered from this, this narrative that indigenous people have disappeared. I mean, think all indigenous nations certainly have suffered from the sort of last of the Mohicans myth, this idea that as Western settlement expanded, native people no longer exist and they just disappear. But that last of the Mohicans trope is very specific to this community. I saw throughout so many of the documents where tribal members are going back to the East Coast, that they are very frequently faced with people who are saying like, oh, I thought you people no longer existed because of James Van Horn Cooper. And so I think that also just plays a really big role into how we see them not only recover these archival materials, but also their efforts to then change the way that their history is represented in these public spaces and really make their ongoing survival and their ongoing connection to their homelands, even though they were forced to leave their homelands to make those ongoing connections known.

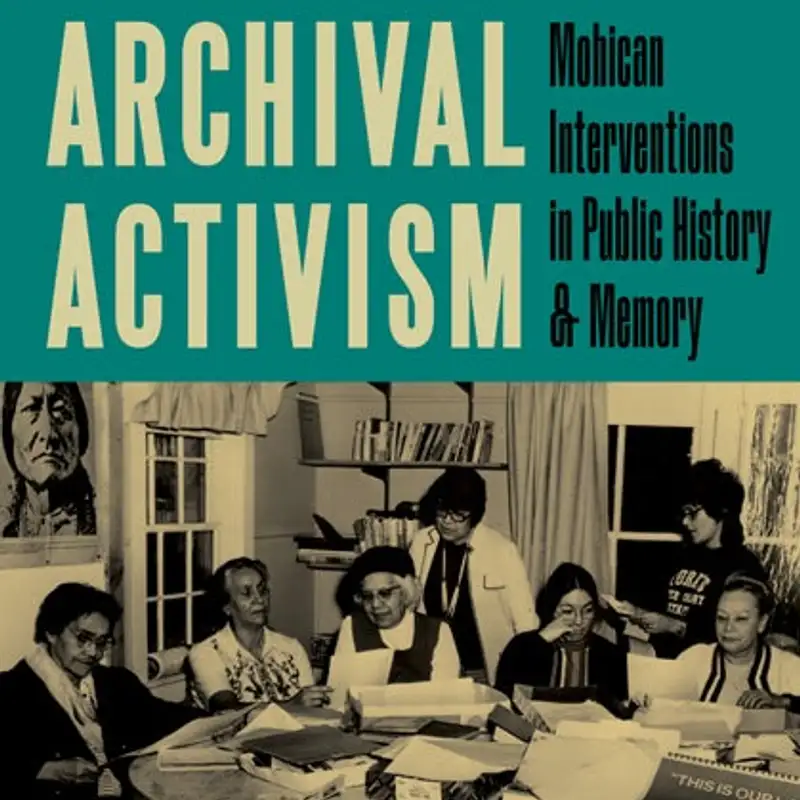

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah, that's such a great overview, especially for people who don't know about the history of the movement of this community and the Stockbridge Muncie Mohican community that has really fought so hard to tell this history. And of course, that's the huge part of this book is the incredible work of the community, particularly women who work at the center of preserving this history, documenting this history. And although this had been going on for, you know, in different iterations over many years, as you know throughout the book, It particularly comes to a head in the late 60s and early 70s. I just want to turn to the cover of your book for Indigenous Archival Activism, has this incredible image of all of these women sitting around the table from the historical society coming together and working in this room together with all these documents around them. I'm hoping you could tell us more about these women and really how you came to know their story.

Jennifer O'Neal:What is unique about the story of these women, particularly about many of the women who really fought to save these records?

Rose Miron:Yeah, absolutely. So I think, you know, the two women that are really at the center of this story and are both kind of pictured in that cover image are Bernice Miller and Dorothy Davids. And Bernice and Dorothy are sisters. So they have, you know, obviously grown up together and have this shared interest in making sure that the tribe's history is preserved and taught. And Bernice was married to Arvid Miller, who just before the historical committee was founded, Arvid had died.

Rose Miron:But for the last thirty or so years, I believe prior to that, he served as the tribal chairman. And so, really kind of from the moment of the Indian Reorganization Act in the 1930s, ARVID was kind of stepping into tribal leadership and like tribal council meetings were being held in his and Bernice's home, there was an immediate sort of start of archiving, you know, meeting minutes and other materials. And tribal leaders at that time started to actually travel to different archives and try to gather information in order to be prepared to go through the Indian Reorganization Act. That at that point, like in the 1930s, you know, they were looking for maps, different kinds of government documents to really highlight this kind of ongoing relationship that they had had with the federal government in order to create an IRA constitution. So ARBET is a big part of that work.

Rose Miron:And though it doesn't show up necessarily on the page, I think Bernice probably was too, as, his wife and as somebody who was the one kind of organizing all of those archival materials in their home. And over the kind of thirty or so years that Arvid then served as a tribal leader, he continued to do some of that traveling to different archives. And he would come home with these copies of materials and Bernice was the one sort of organizing them, and making sense of them all. So she kind of had that background as somebody who was organizing those materials. And it was always her and Arvid's dream to create a formal, you know, library and museum that was more accessible to tribal members outside of, you know, just being in their home.

Rose Miron:And the sort of literal spark that happened to kind of create the historical committee was that shortly after Arvid's death, Bernice's home caught fire. And so all of these materials that they had been collecting for the last several decades, you know, nearly went up into flames. But neighbors actually rushed into the house to save all of the documents that they had been collecting and that they had located in other archives and copied and carried them out before they were lost to the fire, which I think is just a huge testament to how important these materials were to not only Bernice, but also to the larger community who immediately sort of recognized that they needed to be saved. And so after the materials were rescued from this fire, Bernice started working with Dorothy, her sister, and other women in the community to really kind of make this dream into a reality. Thinking about how do we make this into a actual public library archive museum?

Rose Miron:And Dorothy had a background in education. She was teaching at the University of Wisconsin Extension, and had a background in really social justice based education. And so she kind of brought that aspect of her background to the historical committee. And I think together that is what really formed this very unique committee that took on a lot of things really from the get go, from locating and copying and bringing back additional archival materials, but then also really thinking about how do we use these materials to change representations of history and to better educate both native and non native publics about Stockbridge Muncie history. And the other women in this photo range from, you know, other relatives.

Rose Miron:Some of them are Bernice's daughters. Sheila Miller is in that video. Molly Miller and Leah Miller are not in the photo, but they become really important historical committee members as well. And then we have a number of other women in the community who come together to start to do this work. And I think, you know, as I, as I went through the project, this was one of the things that I think the historical committees members themselves really helped me understand just in thinking about like what the role of women is in the community in terms of passing on, language and especially, education and kind of being responsible for the education of future tribal members.

Rose Miron:And you know, that's not something that showed up super plainly in the archive, but it was something that I came to understand from talking to these women as to why it was a group of women who sort of took up this initiative.

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah, such incredible work that they did. And something so surprising to me as I read your work and hearing about just what this community was doing was they're really at the forefront of doing what today we refer to as the return of collections or digital repatriation. They were really at the forefront or going out on their own to actually find the documents, copy them. And as you mentioned, whether it was the women or ARVA doing the work, but they would often also have to transcribe them by hand because they couldn't have them copied. So just the amount of labor that went into this is just incredible, as well as the innovative ways that they were coming up with to get those records back, whether if they couldn't do it physically, they were doing it intellectually, and that they were trying to be so innovative in the ways that they were doing.

Jennifer O'Neal:It was also incredible. In addition to that, they were also what I found really amazing in the way they were forward thinking with doing this work, not only returning the archives and going out to get those collections, but also when they did receive either a copy or they had a book in their collection that how they would also have like a bibliography and an index. Can you tell me a little bit more about that or what, maybe what was one of your most interesting, interactions about that or something maybe that you found so interesting about that? Because I just found that incredible as a historian, knowing the incredible amount of work that that would take for them to do. Yeah, I'm just very interested in that aspect of their indexing.

Jennifer O'Neal:If you could tell us a bit more about that.

Rose Miron:Yeah, absolutely. When I started finding those materials in the archive, I was really blown away because that is not really something that I had seen in other places, especially for those of us who work in native history in some capacity, we are so used to having to like dig through the collections of largely white settlers and looking for kind of traces of native people and having to do like a lot of reading against the grain. And as you said, that's so much work, you know, and you have to like come up with these creative search methods to try to kind of unearth these people who are there and who are, you know, in these historical moments with the people who are actually doing the writing. But it's it takes a lot of work to kind of parse through all of that. And so yeah, I mean what we see in the tribal archive is that tribal members, mostly members of the historical committee would go to archives, especially those on the East Coast where a lot of these materials existed.

Rose Miron:And they would copy like a full item. Like I think one of the examples that I use in the book is the Journal of John Sargent Jr, who's the son of the first missionary that the community works with. And he later works with the community in Upstate New York. And so they'd copy his whole journal. But his whole journal is not relevant to Stockbridge Muncie folks.

Rose Miron:Some of it is. But as somebody who would be kind of wading through that, it's easy to get frustrated or discouraged as you're trying to kind of find the information that's relevant to you. So in addition to that journal, when you open that in the tribal archive, you're also going to see an index where historical committees had gone through page by page of that journal and specifically marked which pages were relevant to the community so that it was easier for other tribal members to then go in and be able to more quickly find things that would be of interest to them. And again, this is just not something that we typically see in larger archives at all because, you know, I think like in part the role of the archivist is often seen as like being neutral. Right?

Rose Miron:And so like we're, archivists are supposed to sort of like present this knowledge and certainly there are finding aids that tell us what is in there, but not necessarily like relevant to a certain group of people, if that makes sense. And so I think what makes the tribal archive so unique is that it's really meant for tribal members. These materials were brought back so that they could be accessible to tribal members. And so these indexes were created to facilitate research by Mohican people. And I also really love, in addition to the creation of these indexes, just kind of the pulling out of certain materials and reorganizing them in collections.

Rose Miron:So this is something, for instance, that we see with the collection of Hendrik Oppenhott, who is kind of an early Mohican orator and writer. And a lot of his writings are kind of stuck within different collections, like at the Massachusetts Historical Society. And again, like the kind of archival principles tell us that we should like keep those materials together. But I really love that the community kind of pushed back against that and like took Hendrik's writings out of those other collections and placed them in a new collection called the Hendrik Oppenhappenbach Collection in their own archive so that people who were interested in researching him could look at his writings together rather than have to kind of parse through another set of papers.

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah, just the immense amount of work that they did around this is just incredible and something you don't always see. I've also heard you say just how, you know, if there's any historian or anybody wanting to work or do research on these communities, they of course have to go to this collection. And they have done such an incredible service to those of us who do want to know about this community, but also have done it in such a way that they've culled these collections, they've, you know, have these bibliographies and these indexing and annotations of, yes, this is a good book or don't look at this. The fact that they have done that work is just incredible and something that you don't always see. Something that I look at in my own work and something I'm currently working on and look at is, of course, during this time period of when this committee really is created in the late 60s, early 70s, of course, also in the height of the rise of the Red Power movement, American Indian Movement, where a lot of that activism is very performative or takeovers of buildings and very much more in the public eye.

Jennifer O'Neal:However, a lot of the work that is being done by this community is very much behind the scenes. And there are a lot of activists also doing a lot of work behind the scenes, whether it's in the legal sphere, in policymaking. So very much interested in what's happening behind the scenes that you don't always see that is kind of a different intervention in doing activist work during the same time period, but then going forward, how do these activists make their work known? And then more importantly, how do they continue to sustain it, especially not only in their own community, but also financially and how do they make this work sustainable during a time period where so much is happening, not only by activists, also politically, legally, where you're having the repealing of termination coming and self determination act and a lot is happening, but it's still difficult to make a lot of these initiatives continuing. So how did they sustain this work?

Rose Miron:Yeah, it's a great question. And I mean, every step of the way through this project, have been like, I have asked myself that question because I'm just like, this is so much work and it's amazing to just see how often this committee met, you know, how tuned in they were to the kind of activism that was happening on a national level. And certainly, like, I cannot speak for them, but I will just say, like, from reading the minutes and from talking to the people who were, you know, in the room when when these things were happening, it really seems to me that they saw the work that they were doing as part of the historical committee as really part of these larger movements and as connected to these larger movements. You know, I think as the tribe is not necessarily like directly threatened with termination, but their neighbors, the Menominee Nation is one of the nations that does get terminated. And so like, you see that come up as a topic of discussion in the meeting minutes.

Rose Miron:Right? And I think you see that, like, there are some land battles that happen, in the late twentieth century where the historical committee is involved in, helping with identifying research materials that can help kind of make these cases in court about different parts of the reservation that are in question of, whether or not they are part of the reservation or not. And so I think, like, historical committee members really saw their work as an inherent part of the tribe's ability to exercise its sovereignty. I mean, and I think that goes right back to the roots of how this archiving process, was sort of started in the twentieth century. You know, like in the book, I talk about how the practice of, like, recording and remembering Mohican history goes back to time immemorial.

Rose Miron:And I think that's absolutely right. But the sort of moment that the tribe is, like, actually starting to collect physical documents and archive them in a home in the way that we think about an archive today happens in the 1930s when the tribe is being asked by the federal government to recognize themselves in this way. And so I think the women who started the historical committee and then ultimately with the historical committee when it's founded, really sees themselves as an, a key player in making sure that the tribe has the ability to exercise its sovereignty in everything from these land battles to repatriation eventually, to more public representations just in terms of how their history is being told. So I think they see those things as connected. And then just in terms of like the, you know, very logistical aspects of this, I think like these women are just incredibly savvy, you know, the initial fundraising that they do and the way that they've kind of financed these initial trips is through collecting and selling aluminum cans and saving up.

Rose Miron:And to, you know, finance these trips across the country. And then, you know, you can see they're applying for just tons of grants, across their, across the 70s and 80s. Anybody who's worked on grant work knows you apply for a lot and you get a couple. And so they're kind of piecing together these small different grants. And then eventually, as some of this work is starting to grow conversations about NAGPRA are happening at a national level, the Tribal Historic Preservation Office gets founded.

Rose Miron:And so that kind of is able to take up some of the work that these women have been doing. And then, kudos to the tribe who in 2018 actually started the Department of Cultural Affairs, which sort of like really makes a department within the tribal government that is addressing these issues. So I think we really see all of that kind of grow out of the historical committee's work, but it's really just that these women were incredibly committed to what they were doing. And I think they really saw what they were doing as part of these larger activist movements, even if it wasn't being recognized as such, because it was sort of happening behind the scenes. I would be so curious to hear what you've seen in your work with this too.

Rose Miron:If you've seen similar things or how, how you see people sustain this work and make sure that it continues.

Jennifer O'Neal:Well, know trying to sustain projects like this or in tribal communities is just one of the most challenging initiatives that tribal archivists, tribal historians, or librarians, or museum folks often face. That's why I was so impressed by just what this community has done and how they have sustained it for so long. We hear over and over again just how challenging this is and of course any tribal community that is either trying to sustain their tribal archive library or museum or who is trying to start or applying for grants or just all the different areas that they have to manage is a huge undertaking. And very similar to the story here is you see in many communities, of course, that it's often not somebody who has gone out and I'm going to go to get a master's degree in archives and museums or information studies. It's somebody in front of the community who cares deeply about this.

Jennifer O'Neal:Not that they're also not going to school to do this, but they care deeply about the community and maybe they've been tasked with doing this work. And I know I've also heard you talk about the work that Lisa Brooks has talked about, about our rememberers, those that are the keepers of native history and stories. And so many communities come at this from all different ways. And the people who are tasked with doing it come at it from different ways they've been asked to do this. But the sustaining of these programs and the funding that it requires, whether some are able to get the funding from their own communities, but then others have to fight to get all of these different grants, whether it's with IMLS or with NEH or other, private foundations that are willing to provide funding for this, like the Mellon Foundation.

Jennifer O'Neal:So it's really a huge undertaking to continue to sustain these projects. I guess, yeah, that's one of the main reasons I wanted to ask that question because I'm just so incredibly impressed by the ways that this historical committee not only was able to be founded, but also to sustain over so many years. Just the effort that it takes from the community and the funding that it requires is just incredible. You know, recently, particularly over the past, I would say ten to twenty years, we're thankfully seeing more successes in tribal communities. And I think that's due in part to the funding that they're able to get in their from their own communities, funding from outside funders, and also some partnerships people have been able to from outside institutions that have also been able to collaborate with tribal archives, but it does continue to be one of the biggest challenges is just sustainability education.

Jennifer O'Neal:Luckily there's incredible programs now that are working to provide that education as well as to connect tribal communities with funding that they need, but it continues to be the biggest challenge. When you go to conferences like the incredible Association for Tribal Archives, Libraries and Museums, a lot of folks are talking about just sustainability and and how you continue projects like this. But luckily it's luckily it's happening. I know another thing that you know, especially most recently in the past ten to twenty years that we're seeing a lot more of is the return of archive collections, return of collections. It's not always significant, but it is there.

Jennifer O'Neal:And that's what I also found interesting about the story and about what you looked at with this community is they were also at the forefront of doing a lot of that work, not just in what we've already talked about with the going to collections and copying collections and returning intellectually those to their community, but they were also at the forefront of physically trying to get collections back. And I know one of the most significant ones that you've talked about both in the book and then in an article is the Bible that they work to have returned. You go into all of course, all the details of that in both of these pieces that you've written, but I was wondering if you could talk just a little bit about the significance of that because I'm always wanting to point out and look toward kind of these beacons of hope for tribal communities that are wanting to see how can this be done, can this be done, and what are the ways and to not also not give up because I know particularly this case it took them many years, started in the 70s and it went through different iterations, but can you tell us the significance and how that impacted the community?

Rose Miron:Yeah, absolutely. Just to give a little bit of context, this is a two volume Bible set that was gifted to the tribe in 1745 by the chaplain to the Prince of Wales. So this is sort of when the tribe is in Stockbridge and they've like accepted this mission. This two volume Bible set is given as a gift of, you know, kind of celebrating Christianity essentially. As tribal members were removed first from Stockbridge and then, you know, as we talked about earlier, kind of through the Southern Great Lakes and into what is now Wisconsin, they carried this Bible set with them and, brought it to Wisconsin with them.

Rose Miron:And there was always a caretaker assigned to oversee and to protect these very precious objects. And again, as you said, I go into this story in a lot of detail in the book and the article. So if you're interested, take a look there. But in short, the items were stolen in 1930, and they were sold to a white collector on the East Coast who then put them into a museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, which is where they were gifted initially to the tribe. And so as you mentioned, Jennifer, the kind of fight to try to have this two volume bible set returned to the tribe began in about the '70s.

Rose Miron:And they were repatriated in 1991, kind of just before the passage of NAGPRA. So, they were it was not a NAGPRA repatriation. It was something that the historical committee really committed themselves to and worked at for, you know, twenty plus years, as they were trying to to get these items back. And I think that just in thinking about the significance of both that repatriation, but also the items, I think that, you know, something that people often ask me as I was working on that aspect of the project were like, you know, why Bibles? You know, like what is the significance of these Bibles?

Rose Miron:And I think that for so many tribal members, it's, I mean, for some of them, I think they are important as religious objects. Know, a lot of Stockbridge Munsee people are Christian and they, and they do think of them as religious objects. That said, a lot of people also just see them as a very important connection to this place and to this moment in their history. And I think that that became really important as they were working to to get these items back. And I think this was one of the moments too, as I was working on that aspect of the project that I realized how important the archive was in connection to some of these repatriation projects.

Rose Miron:Because what we really see in the way that they are able to be successful is that they create these two booklets of documents that they circulate across the country. One is called A Brief History of the Stockbridge Bibles, and it includes, you know, published works about Mohican history and correspondence between the collector and the person who stole the Bible. It includes letters from tribal members. And then the second is this collection of documents called the Stockbridge Bible, documents relating to its recovery. And again, it's all it's basically just a booklet of primary sources where they're saying, you know, showing like these are the firsthand accounts of how the tribe has cared for the Bible.

Rose Miron:This is correspondence between the tribe and the museum who's holding these items. And they circulate these materials to all kinds of people from politicians to friends of the tribe, to different celebrities who then write letters of support. And they essentially just coordinate this massive letter writing campaign that eventually gets the museum to fold and to agree to return this two volume bible set to the tribe. It's not without a lot of challenges. And again, if you're interested in that, the article especially kind of gets into like the behind the scene politics of what was happening and the kind of larger contexts of what was happening in conversations leading up to the passage of NAGPRA during this time.

Rose Miron:But I think it just really attests to how the kind of collection of these materials, these archival materials, really allowed the historical committee to put together a case for why this two volume bible set should be returned to the tribe and really just speaks to how access to archival materials can facilitate, exercises of sovereignty in this case, directly related to repatriation. And I think it also just really speaks to the importance of how like new narratives can be created through these kinds of things. When the Bible set was displayed on the East Coast in the Mission House Museum, which is this museum that is still in Stockbridge, you know, it was told within a story about missionization and colonization and John Sargent and his family. So the Mohicans were sort of a piece of this larger colonial history of missionization. Now in the tribal museum, it is a very different story.

Rose Miron:They are a piece within Mohican history, and they're telling a story about missionization is one piece within the larger history of the Sacred Munsee community, not the other way around. And so I think we can see like how the return of these objects just also really changes the way that, these narratives about Mohican history are told, where Mohican voices and stories really get to be front and center as opposed to kind of a piece of this larger narrative about colonization.

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah, and I'm glad you pointed that out because I think that's what's so unique about this example is just their tenacity for their letter writing campaign, but not only in that, but also in how once being able to have the materials returned back to them, how they use that to tell their own story. That's really, of course, I think a huge theme of your book and your work. And I know I think I've heard you talk about before when you think of your work, I think you think of it, you know, these different pillars that are that you see in the book, like with access and of course sovereignty, but that they're creating these new narratives that of course that have always existed in their own community, but that maybe haven't really risen up to other historians or to how others have viewed their community, which is really so important. Of course, a huge part of this book as well as not only telling the story, but really at in the conclusion of the book, really give a call to action to outside institutions, non native institutions, and the importance of working with communities like this and to really center the work that tribal communities do.

Jennifer O'Neal:So what advice or what kind of call to action do you give to institutions that may want to work with these tribal communities or what role do you see that these types of institutions should have? And I think that also then plays into the conversation we wanted to have around like the protocols and other conversations, but I wanted to hear what your call to action would be for institutions.

Rose Miron:Yeah, absolutely. That element of the book is something that really developed as I was working for the boarding school healing coalition. And then as I was working at the Newberry, because I realized that like the kind of the three pillars that you mentioned, the like access sovereignty and new narratives, like that kind of framework was not part of my dissertation. It was something that kind of came, that I came to by working in these institutions because I very quickly realized that explaining, I was trying to explain to people the importance of archival materials and how archival materials sort of sit at like the nexus of all of this kind of work that native communities are doing to change representations of their history, I found myself kind of describing access and sovereignty as like the levers that folks can pull in order to create new narratives that are more centered on native voices and that are simply more accurate. And so I ended up really writing the conclusion in particular, but also just other aspects of the book and thinking about those pillars as a sort of call to public history practitioners for them to really understand that archival materials are so important for this work.

Rose Miron:But if native people don't have access to them and if they're being interpreted without indigenous knowledge, they're useless. They're not nearly, they're not going to create the kind of new narratives that we should be creating. And so I, yeah, I think I really encourage people to think about both of those things, just in terms of like what they can do within their institutions to improve access for native people, but also really making sure that native communities have the right to control how those materials are used and accessed. I really took a lot of that aspect of the book was really, I really learned from reading the protocols for native American archival materials And just learning more about the kind of larger movement of data sovereignty that has been happening across the nation, you know, and across the world really in the last, you know, ten, fifteen years or so. And so, yeah, I think that was definitely a big part of how I was thinking about public history practitioners.

Rose Miron:And yeah, I mean, I would love to hear what you think about that as an author of those protocols, As you were talking earlier about some of the changes that have happened in the last ten to twelve years with tribes being able to get more support for this kind of work, I think so much of that is actually directly tied to the protocols because they have been able to really take those to institutions, libraries, museums, and say like, these are the best practices. And then we're seeing more larger foundations that are willing to then fund that work, you know? And I think that that really comes from setting a really clear set of, best practices that people can follow. But I know that like the, the work of writing the protocols and actually getting them to be approved by, some of these major organizations was really an uphill battle. And so I would love to hear a little bit more about like how you experienced that and just what you've kind of seen in the changes in the last ten years or so, as the protocols have become more cited and, and, and better shared with different institutions and accepted by various institutions.

Rose Miron:I guess also like what you see, what's next for that work.

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah, so the protocols were developed in 02/2006. So we're actually coming up on like twenty years.

Rose Miron:Oh, twenty years, yeah.

Jennifer O'Neal:Which is, wow, incredible to think about. But yeah, was very lucky to be part of the group in 2006 that was part of these incredible conversations that where we developed these guidelines and policy together, with a very incredible group of, 19 other archivists, historians, anthropologists, both native, non native coming together because just to remind folks, you know, there's no national policy on Native American tribal archives prior to that, that provided guidance for non native repositories on how to care for our materials. And so that's really the void and the gap we were seeking to fill. So many of us were seeing in the field, in these institutions that we were working in, communities, the lack of native voices, and also just wanted to ensure the correct care of culturally sensitive materials. In particular, of course, NAGPRA had been passed by that time and was in effect, but there was nothing that was helping to protect archival materials.

Jennifer O'Neal:You can, you know, think of that of many of the different types of materials you talk about in the book, whether it's records or, but it also includes photographs, recordings, all the things that are produced in our communities that are not protected under NAGPRA. And since that time, I think the biggest thing to think about in the context of this larger movement of both the protection of Native American archives, as well as now indigenous data sovereignty is that I really see and kind of what I've tried to reiterate to a lot of folks I meet with about this topic is that I really feel the work that was begun with the protocols was really the start of indigenous data sovereignty movement. I know a lot of folks talk about it, with the start of the passage of UNDRIP, the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. That of course was a huge part of it because so much of that is embedded in a lot of the articles in UNDRIP. But there's really a long legacy of this work happening and I even see it with the Stockbridge Muncie Mohican group, they're doing the work.

Jennifer O'Neal:So I'd really encourage people to think about it as not just a movement, particularly the indigenous data sovereignty movement and field, which has really grown over the past, I would say fifteen years and longer than that too, since the Patches of UNDRIP, but that this work had been happening for years before this. And it would not exist without building upon the incredible work of tribal communities, just like the ones that is in your book, as well as the ones that so many of us have worked with. And so yes, when we developed and then had and took it out to so many different organizations and communities for endorsement, as well as for implementation into their institutions, it was extremely challenging because at that time NAGPRA had been passed and that was already challenging. So to fight for our archival sovereignty in that context, it took so many years. The first phase was just educating people.

Jennifer O'Neal:Why are Native American archives different? Because of sovereignty. We are sovereign nations. And of course, educating about the displacement of archives in so many of these institutions. So, so much of our time was just spent educating folks, particularly through the Society of American Archivists, as well as through other organizations.

Jennifer O'Neal:And because it took so many years, it wasn't actually until later in 2012 later when SAA and other organizations actually endorsed it later in 2017 and 2018. So it came quite late for official endorsement for some organizations, but that isn't what was always important to us. I'm sure that's great if these organizations finally endorse it, but we were not going to wait to do the type of work waiting on organizations that were still doing their own work, doing their soul searching of we already knew this. And so what was more important to us was to see how institutions, how organizations, how individual researchers or archivists were implementing this work. So that's what was important to us and that's where we saw the incredible work happening, is the people who were doing it and that didn't need an endorsement to do it.

Jennifer O'Neal:Because that is also where we continue to see and historically have seen where this work happens. Federal, state, even local laws are not always supportive and historically are not supportive of tribal sovereignty. When we try to work within those confines, it's not always helpful or useful for us. So that's why we have to create our own policies, our own guidelines, and have those and hope that people follow them. And of course, it is our hope that this does become at some point a national policy or international policy and of course we have things like UNDRIP and the care principles that have emerged from Indigenous data sovereignty, which I feel are a lot of the same values and statements and guidelines that we also made in 02/2006.

Jennifer O'Neal:So I feel like it's an extension of that work, and we are embedded with and we are working with in that sector of indigenous data sovereignty. But really, like I said, this work has been happening for so many years and we just really look forward to seeing hopefully how, what are these next steps going to be in policymaking? Meaning really one of my next big projects I'm working on is, since we're coming up on twenty years of the protocols, going back and talking to a lot of the folks who helped to draft the protocols, were some of the first people and organizations who were adopters of doing this work, having those difficult conversation, how things have changed in our field, and maybe ways they haven't changed. But I think one of the biggest areas also we're looking at is the return of collections. And that's specifically why I asked that question about the Bible, because how can we return even more collections to communities?

Jennifer O'Neal:And of course, there are the collections where maybe that isn't the best option or fit, but there are many collections where they do need to be brought home to these tribal communities who have worked so hard to develop these tribal archives, these spaces where they do need to go back home. I was also recently just part of a group that had a special issue within the transactions volume of the American Philosophical Society where I talked about this issue. So if people want to know more they can go and read that special issue but it was actually all about language archives and how the incredible work happening around tribal languages and those collections. Really my call to action in that was what are the ways in which we can get more collections back into tribal archives, in tribal communities? Because yes, digital repatriation is one avenue, but how can also institutions look at other avenues that are going to also ensure that collections can go back to communities?

Jennifer O'Neal:So that's a bit of kind of where I'm hoping to see things go.

Rose Miron:Yeah, that's great. And I think I end up having a lot of conversations with other institutions too about just like what the kind of work that they could be doing. And of course, like the first thing I do is always direct them to the protocols. But I think what I have said, like, to many people and and even within the institution that I work for now, like, is, you know, let's not wait for a federal law to start having these conversations about the return of collection items. Like, let's start having those conversations now.

Rose Miron:You know? We should like, I I genuinely hope that there's a federal law at some point that requires that kind of return. In the meantime, like we should just be doing it because it's the right thing to do. And we should be opening these conversations with communities. And so I think that, you know, like you said, there are definitely institutions that are starting to do that now or the past five, ten years or so, which I think is great to see.

Rose Miron:I hope that that work will continue into the future.

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah. And what's incredible to see is celebrating those moments of institutions that are doing this work and really who have led the way over the past twenty plus years in doing this work. And that's why, again, I try to find those pockets of hope for tribal communities so they can see there are institutions that are doing this work, they're doing it in the right way. And there are also institutions who are wanting to listen and stepping back and saying, we know maybe in the past we haven't done this correctly, we're pausing, we're learning, we're building partnerships. And I think that also applies to anybody who, and not just archivists, but historians and researchers who are wanting to work with communities to be able to approach that in the same way because I think there's a lot of the values and guidelines within the protocols, as well as in the UN declaration of the rights of indigenous peoples that applies to doing research with indigenous communities, following those, it's in the same spirit and the spirit of wanting to do the right thing.

Jennifer O'Neal:Hopefully we are on a better path and that we have all of these great years of learning from, the protocols, from the UN declaration of rights of indigenous peoples, also just connections with other indigenous folks across the world that are helping us to continue to move forward and see what will come next, is also very exciting. Just the last question I might ask you, particularly if there might be any graduate students or undergraduate students that might be wanting to engage in work like this, what's a piece of advice that you would give them? You could think back to your undergrad or graduate self. What piece of advice would you give to students who want to do this work? Because I work with a lot of undergrads and graduate students and I of course want to encourage them to do this type of work and I'm curious what you would say.

Rose Miron:Oh my gosh. I have so many things to think about. I'll try to limit it. If I could just say maybe two things. The first thing I would say is just that I really strongly believe that research that is about Native history should be led by the priorities of tribal communities.

Rose Miron:So I don't think that means that, like, you know, I am a non Native scholar. I don't think that that means that non Native scholars or Native scholars who are working with other communities that are not their own. I don't think that that means that, like, we all can't come up with ideas that we're interested in or, like, find things in the archives that we wanna write about. But I think, like, as soon as you are thinking about going down the path of working on a project, like, some of the first things that you should be doing is talking to the communities whose history you're interested in writing about, whether that history happened in the twentieth century or the seventeenth century. Because I think that there's an abundance of, of research being done and that's wonderful.

Rose Miron:But I think, like, I really wanna see a much bigger part of research happening in Native American and indigenous studies. And I think we're moving in this direction that is really, in alignment with what tribes need and want and what they are interested in. In this moment that we are in where consultation is becoming more common and encouraged, which I think is great, it also means that tribes are getting, like, inundated with requests for things that may or may not interest them. And so I think, like, instead of thinking about, oh, I wanna make sure that, like, whatever community I'm interested in writing about kind of signs off on this. Like, I think researchers should be having conversations with those communities about their interests and really building from there, if that makes sense, rather than, rather than kind of centering one's own interests.

Rose Miron:So I think that's just like the first thing that I would say is that like any kind of consultation that is gonna happen, like has to begin really early. And as researchers, we should think of ourselves less as like people driving our work and around our own interests and more about like, how are we being in service and how are we being in reciprocal relation to the communities that we're working with? So that's the one thing, that's one thing I would say. I think the other thing I would want to say that is something that I hear a lot from graduate students and also I guess is kind of sadly one of the questions, one of the most common questions that I've received about this book is I get a lot of questions about like bias and whether or not the book can really like be a neutral telling of history, given how closely, like I worked with the tribe. I get this mostly from like people who are like in really traditional history disciplines.

Rose Miron:And so I guess I just want to say to graduate students who might be in that position, who might be working in, like, very traditional history departments, and historians who are, you know, coming from this world in which we are told that we have to be kind of, like, neutral. I guess I would just say that mine sort of like hill to die on, if you will, is that like, there's no such thing as neutral history and that we all are bringing our own biases into the work that we do. And ultimately, like, you know, if I had written this book without consulting the community and asking them for feedback on drafts, like it would have been a worse book because I would have just gotten things wrong. You know, I think fundamentally as a non native historian, there are just things that I'm never going to inherently understand and never going to be able to interpret without guidance. So I think there are still a lot of people out there who are writing books about native history without talking to any contemporary communities.

Rose Miron:And kind of, and they say like, well, are these like unbiased texts because they're relying on archival materials alone. But I think we have to recognize that like there's bias in archival materials. There's bias in whoever is writing these new historical narratives. As historians, like we have to just acknowledge that like no work is neutral and in order to simply create better scholarship and more responsible scholarship, we can and should be working directly with the communities whose research we are writing. And I think that applies to both, you know, Native and non Native historians alike.

Rose Miron:Yeah, I'm curious about your answer to this question, though. What advice would you give?

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah, and thank you for yours. I think those are all so important to remember. I think in the very similar questions that I get, one of the biggest pieces of advice I usually, of course, in addition to everything that you said, of course, working with community hearing and listening to what are their priorities is also the slowing down of the process. And I know that can be very difficult, particularly in the academic setting and schedules and calendars that many undergrads as well as graduate students are placed within, particularly if they're finishing a thesis or a dissertation, which we all know there's certain kind of benchmarks and deadlines that you work up against. So something I always encourage students on is I know you have certain deadlines and calendars to meet, but as much as possible slowing down the process so that you're, and knowing it's going to take much longer than you think it is because building those partnerships and relationships takes time and you're working on their time, they're not working on your time as much as you would like them to.

Jennifer O'Neal:And so knowing that the dissertation or the thesis that you might work on is just that moment in time and what you can work on to that point. However, it's important to remember that the partnerships that you're building with these communities, those you should not see is just a one time thing. You need to continue those for the long term for what might come after just how you've done. You wrote your dissertation and then now you've wrote the book and I know you've continuing to work with the community. So to look at these partnerships as long term commitments and to really be embedded in that, and that's what I've seen as most successful.

Jennifer O'Neal:And of course, all sorts of other advice I can give as well, but I think that's one of the biggest, just to slow me down the process and building these really long term partnerships. But, I just really applaud you for the incredible work that you've done with the community, and how also I know I've heard you say how the proceeds from the book go to the community and to continuing these projects, as well as with the oral history, that you did with them, that the copyright lies with them. That's embedding, the protocols and data sovereignty into this work. It's just incredible to see because that's really also what we want to see. We want to see all of that going back to the community.

Jennifer O'Neal:And so it's just amazing to see the work that you've done. So thank you so much for sharing your story with us today, as well as just being in conversation. It's incredible to see the work that you've done. And I encourage everyone to go out and buy her book, Indigenous Interventions in Public History and Memory, and to continue to see the incredible work that Rose is doing with this community as well as many other projects. Just thank you so much for being with us today.

Rose Miron:Well, you. Absolutely. And thank you, Jennifer. I just want to echo back that, you know, your work was so important to me in writing this book. I learned so much from reading the published articles that you have about archival activism and from the protocols, which of course you helped author.

Rose Miron:And so thank you for doing all of that work that has helped so many of us in the field learn about these things. And I know that you're kind of working on a book project right now that I can't wait to read when it comes out.

Jennifer O'Neal:Yeah. Yeah, it'll be great to see all the wonderful things that come out of this field and this work that so many people are doing. I am just elated that finally so much is being done in this field. So just, it's been really great to be in conversation. So thank you so much.

Rose Miron:Absolutely. Thank you.

Narrator:This has been a University of Minnesota Press production. The book, Indigenous Mohican Interventions in Public History and Memory by Rose Myron, is available from University of Minnesota Press. Thank you for listening.