Is aggression inevitable?

There are all these interesting elements that I think the mainstream account just doesn't even look at. Because you're able to work on these multiple registers, it's bringing in a much more complicated picture.

John Protevi:Just as any social formation must channel its desiring production, so must any sociost or any social formation must channel its violence.

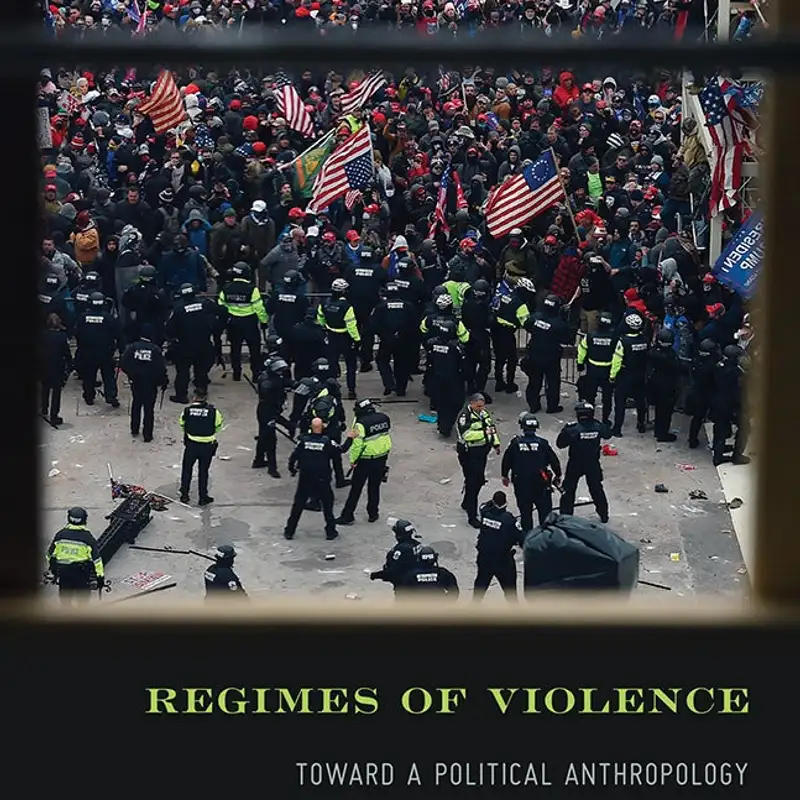

Andrew Culp:Hello. I'm Andrew Culp, the director of the Aesthetics and Politics graduate program at California Institute of the Arts. And I'm so excited to be invited by John Protevi to discuss his new book, Regimes of Violence. For those not familiar with John, he's published extensively, including a whole series of books with University of Minnesota Press, including political affect, life worn earth, edges of the state, and now regimes of violence. And he's been teaching at Louisiana State University as a professor of French studies and philosophy.

Andrew Culp:So, John, thanks again. And why don't you, give us a little snapshot and overview of the book and the project?

John Protevi:Okay. Well, thank you very much, Andrew. I'm really glad to be here with you. And as we've mentioned a few times, it's really great to have the Doctor. Deleuze guy and me.

John Protevi:I'm kind of a joyous affirmation Deleuze guy, but I think we also overlap much more than those that preliminary opposition would let on. I think the readership for the book is really gonna be theory people. I do intervene in debates in evolutionary anthropology, mostly in this book. And in previous books I've gotten into cognitive science and geography in some other ways. So I do try to look at the way in which Dulas and Guattari, who are my major theoretical reference points, how they can open up discussion in ongoing debates in specialist sciences.

John Protevi:But I'm obviously not a specialist in any of those things, but I do try to do my homework and I do try to point out the ways in which I am intervening into ongoing debates. There are several that kind of frame the book here. I do want to intervene in a debate in evolutionary anthropology around the existence and prevalence of war in early hominin and or human social formations. So there's a strong school of thought that says that human altruism or the ability for us to care about and to sacrifice for non kin comes with a strong in group and out group division where you're committed to your tribe and alienated at best or xenophobic towards outsiders. And that's formed in an evolutionary framework of rampant warfare.

John Protevi:So the way that you can get altruism or self sacrifice, which should have been weeded out of the process, is that in a warfare situation those tribes or those groups of people that had a ratio of altruists to egoists would outcompete with war being the selection pressure, those groups which were purely egoists. There's lots and lots of technical debates about whether that constitutes group selection or not, but it's a common way of looking at our ancestry, our human nature. So basically we're the descendants of victory and warfare. Some of that victory entailed a cultural process whereby some of the people had sacrificed themselves for the victory and warfare. And that's how altruism comes from.

John Protevi:There's a minor, to use the dualism rhetoric term, there's a minor science in the margins of that dominant paradigm that calls into question whether, in fact, our evolutionary environment was one of rampant, intense, infrequent warfare. There was a lot of discussion about how to define warfare. I tend to have a kind of strict definition of warfare that it's anonymous group violence. And there's a series of arguments why, if that's your definition, that there wasn't war as we would now know it prior to about seven or 8,000 years ago. So there's archeological arguments, there's ethnographic arguments, and a number of things that I try to get into.

John Protevi:But the book is called Regimes of Violence, so I'm not saying that no one ever hurt anyone else in human history. What I am saying is that it's not an evolutionary push towards intergroup violence, but that our human nature is open enough or plastic enough or to use Dullo's term multiplicitous enough that conditions for cooperation were just as prevalent, if not more prevalent, for conditions of warfare in the past. So that we're open to the ability to create peaceful conditions if we can arrange to do that.

Andrew Culp:Yeah, that's amazing. And so if we zoom back a little bit, maybe the Lycians, a few of them might be scratching their head and saying, wow. Where is this coming from? So some of it might be these big debates in evolutionary psychology that you use as a foil in this chapter, maybe most famously, you know, where they say humanity is this killer ape, and so they have these primitive instincts that drive everything. But also I'm thinking, what are some philosophical concerns that you think this connects to or other fields that makes this like a truly interdisciplinary intervention, even though you're mining these minor sources in such a deep and important way?

John Protevi:Well, thank you. I think one of the things I'm most interested in, so when I did my dive into cognitive science, I took up the inactive school for Francesca Varela and Evan Thompson and Ziku DiPalo and Hannes de Gaeder and a number of people, is sometimes seen as part of a 4Ea, embodied, inactive, extended and affective. I've always been interested in the emotional side of human life And I think that connects with what the laws and quaternary call the libidinal investment in the social field. I do have a chapter that's a critique of ideas only or belief centered notion of ideology. Criticize belief only or belief centered notions of ideology and say that the real action is in people's desires.

John Protevi:So they constantly cite Wilhelm Reich, the masses were not fooled, they wanted fascism. We have to discover the conditions in which people want fascism. Duluthbertari tied that back to Spinoza, which they called the Spinoza question, under what conditions will men fight for their servitude as much as for their liberation. When we talk about affect, I do want to resurrect or emphasize the possibilities for joy. But joy is very tricky, right?

John Protevi:Because you can have passive joy. The Nazis and fascists are overflowing with joy. If you look at the January sixth invasion of the capital, people were having absolutely the time of their lives. So try to distinguish between an active joyous encounter which increases the potentials for increasing positive affect on both sides of the equation. So I turn someone on who can turn someone on so that they can expand their affective range, which means that they can be influenced by and influence others in a wider variety of ways.

John Protevi:Being a joy guy, I don't want to deny that fascism is full of joy. I think the difference is it's a kind of joy of being taken up into a mass, the movement. So there's a connection there with a kind of Freud and Gustave Le Bon fear of the crowd that intersects with a really wonderful book by Jeremy Gilbert on collective politics and how you can have collective politics. There's transversal, to use the jargon, rather than hierarchical or even just flatly horizontal. That also picks up with another book that I really enjoy by Rodrigo Nunez called Neither Vertical Nor Horizontal.

John Protevi:So I do think there are connections with a lot of this stuff towards political theory or even activist stuff. One last thing then I think that the chapter I have on marinage, which is people fleeing enslavement. Marronage has been taken up as a contemporary term for temporary autonomous zones and squatters and hackers and a wide ranging range of contemporary social formation experimentation as well.

Andrew Culp:Yeah. That's wonderful. And I think that gives a very synoptic overview of a lot of the, say, greatest hits that that come in the book. And it has four parts, and it really opens with human nature and your intervention in human nature there, which I think is absolutely crucial for setting up everything else. You know, part two is on political psychology where you have these, like, two contrasting cases, both Berserkers and Esprit de Corre, which began as essays a bit ago, but you've updated and sort of deepened those connections, and I really appreciate that.

Andrew Culp:The section you just mentioned on marinaj comes through a political anthropology and a case for statification as a concept. And then, you know, it ends with those two events, the capital invasion as well as COVID nineteen. And so I I think in that way, it feels like social theory written by someone who really dug into the connection to cognition or other, sciences. But then, of course, you're a philosopher by training as well. So it it it's really this, excellent interdisciplinary work that goes across so many different avenues.

Andrew Culp:And I think that that's maybe something that makes, Deleuze Inquiry maybe not completely unique, but it picks up this French philosophy of science tradition that maybe other people departed from. They you know, in the analytic tradition, I think through philosophy of mind or cognition, they've always sort of kept the sciences pretty close. You know, maybe philosophy isn't the queen of the sciences anymore, but it's still in the mix. Whereas for other approaches, science is really held at arm's length and a distance. So maybe just as like a very big question, like, what do you see the connection between philosophical inquiry or even the social and political questions and how the lesseans can and should approach scientific questions or scientific literatures?

John Protevi:Okay, well that's a big one. Let me start by going into the specific thing about human nature. The concept of human nature has been used either as an exclusionary or hierarchizing, if that's a word, a concept for a long, long time. So I do use the dualism term of multiplicity when I talk about human nature. And I also do think that my entire career is a kind of multiplicity where I try to see ways in which these things might possibly hang together.

John Protevi:Now I wrote this book, the chapters independently, but then spent a lot of time trying to weave them together, not into a coherent narrative, but I usually use the image of an overlapping or overlapping sheath of investigations. My initial entry into all this was reading Manuel de Landa years and years ago. His book War in the Age of Intelligent Machines and also Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. So he explicated what's called either complexity theory or dynamic systems theory. And so there's translation you can do of Deleuze's terminology of singularity, for instance, is like a turning point or a threshold or singularity in dynamic systems terms.

John Protevi:So that was really my entry and then I did get interested in the inactive science thing of trying to work against the notion of a subject who represents the world to him or herself in a kind of picture capture representation. Nonetheless, that was Varela, Thompson and Roche in The Embodied Mind, really try to show the way in which cognition should best be modeled as an organism navigating its world. And its world has to be both salience, that has to mean something to the thing. There has to be valences that the world shows up as a push or a pull, as an attraction or a repulsion. So that got me thinking then, well, did we evolve as human beings on this inactive intellect and emotion together, affective valence and salience and valence kind of way.

John Protevi:What is the world that we've constructed? And that takes me into Auntie Oedipus. It's a kind of mashup I think of Bataille's, we've got to get rid of this extra solar energy, Nietzsche, rule to power, everybody's trying to make larger and larger complexes, and Spinoza's naturing nature. So each social formation has to channel this energy because otherwise the energy would just run smoothly, which for them would be no society at all. So you have to have some channeling.

John Protevi:So then I got to thinking, well, Delissa and Guattari call libidinal investment in the associates, in the ways in which your society channels this energy, that sounds like it's at least compatible with a being who has to live in a world in which there's salience and valence. Things have to matter to it. So that got me thinking about human beings and how do we evolve such that things matter to us, even when it's social patterns or justice for third parties. So it's very well established in biology that animals will fight for their kin. If you do a gene reduction thing, you're gonna pass on part of your gene so you can sacrifice yourself or your children or for people who are closely related to you.

John Protevi:And that's certainly the case with human beings. They will fight more ferociously for their kin than for non kin. But we also fight for justice. We also care about justice. I've got all these things bubbling away that I'm trying to bring together.

John Protevi:So the mashup would be human beings involved as affective creatures who care for the social patterns they're involved in. And I think that goes really deep biologically because we know that social isolation will completely screw up your oxytocin levels, your serotonin levels, your cortisol levels. So it's as deep as possible that if you're not socially connected, that you will suffer. I think that's the way that human beings evolved in a social framework that will channel your desire particular ways. When we get to capitalism though, following de Lisinquetari's thing in Antioedipus, we tend to write down a lot of the previous codes.

John Protevi:All that a solid melts into air, which Marx kind of celebrates as an opportunity to get away from the Bishop doesn't have to approve your startup company anymore by seeing whether it aligns with natural law. What an opportunity! I do think that De Los Aquitari do share that ambivalent relationship to capitalism that it does by decoding. It offers opportunities, but by immediately recoding on private property and re territorializing on the family, you end up owing not gifts to your neighbors, as in what they call primitive society, or tribute to the emperor in the imperial society, but you owe your life to capital because you have to work in order to eat. And you owe an eternal debt of neurosis to your family because your desire has been territorialized into the nuclear family.

John Protevi:Now it's very quick and there's lots of nuances. For me that's an interesting way to try to find a way that you can create social conditions that would allow for experimentation. Dulce and Quetzari use art in a very extended sense to mean sports, which is one of my chapters.

Andrew Culp:I mean, the impressive breadth of this argument is something that I think people will find really refreshing because we live in such an era of hyper specialization that big ideas have been left to Niall Ferguson trying to justify, you know, empire or, you know, maybe the Graber Wengrow book, which you worked through a bit. That's that's really nice. But Steven Pinker or even, you know, these homo sapiens arguments that I think, by making them, like, popular or easy to consume, they really don't challenge much common sense, and they don't give a very sophisticated picture. And so for you, I think the ambition is where it starts, and it's really refreshing. And for me, the thing that I see in it that maybe, you don't see as clearly because you're working from this this joyous perspective is also the line of unbecoming.

Andrew Culp:I mean, right when you start talking about capitalism, it's like that's that's where it becomes really important for DNG. But, of course, in what is philosophy, for them, there's this absolute speed of thought that is this deterritorializing process, and you can sort of reach into the transformative power of the chaosmos. I think it definitely begins with this materialist impulse that DNG already start in Antietus by saying that they're doing a material psychiatry, and they're gonna look at some anthropological sources. You know, of course, they're also leaning heavily on Marx himself, who sort of promoted materialism as the only way to really do transformative social thought. They combine it with Freud, who maybe in a certain way already had a sort of materialism to it, but it leans towards free and detached libido by the time you get to Marcuse or someone else who wants to find the the eros tendency in, a libidinal economy.

Andrew Culp:Each one of your chapters plays in this sort of, like, structure, and it's undoing a little bit as well. Human nature, affective ideology. But then the unbecoming sort of really starts showing up with berserkers, right, where they lose their mind and they go into this state of amnesia. But then the opposite of that that you post to it is esprit de corps where you sort of lose yourself in the group as well, and you sort of maintain your own singularity a bit. But it's really this sort of, trans individuated formation of of the nomad, at least in thousand plateaus.

Andrew Culp:And then in the anthropology section, you know, statification, which itself is like this hierarchy process. But then marinage, it's the flee away from it. It's the undoing. It's it's this disruption of, the settled calcified structure of the state. And then with political events, you know, I don't know, it's a little bit more complicated with the capital invasion and then COVID, and you you treat this really tragic case of a health worker who passed.

Andrew Culp:So maybe I can provocatively ask you sort of you found the structure, you find the development, where's the unbecoming or where's the transformation that's happening in each one of these processes that you find in the very materialist circumstances?

John Protevi:Yeah, I mean, I have mainstream narratives that I try to undercut. I'll give one example in the human nature chapter. There's a curious absence of discussions of joy in a lot of evolutionary anthropology when it comes to food sharing, right? So food sharing is a resource variance insurance. So if you kill a wildebeest and it's too big to eat among your small group, then you invite your neighbors over.

John Protevi:However, they never say it's really fun to have a barbecue. It's just really striking. So that might be one of the places that I kind of unravel it. The mainstream narrative does tend to reduce things to survival and that picks up the Nietzschean thing about his critique of Darwin, everything comes down to a reactive survival thing. There's nothing about the sheer exuberance of having fun.

John Protevi:There's a curious utilitarian twist to that too however because as I do not think that life would have been worth living for our ancestors were they not able to find joy.

Andrew Culp:It just shows how far conversations of pre state human life have moved the center of gravity from structural anthropology or even Levi Strauss in particular. I was reading the old translation. You know, there's a new translation of, wild thought.

John Protevi:Yeah.

Andrew Culp:And for him, you know, symbolic life is just as original and probably even prehuman as anything else. And there are other anthropologists who occasionally get sort of thrown into the mix. But when you read archaeology literature, which is often where this stuff happens in the sort of expanded anthropological field, there are people who are very much natural determinists. And so they have this almost strict Darwinian framework of which everything is about survival and or reproduction. And for the Levi Straussian stuff for a while, it was like, well, sure, those things might be fulfilled, but in the same way in which a Freudian or a Lacanian would say that your needs are fulfilled, which is through a very elliptical, socially mediated process.

Andrew Culp:And so, you know, they focused on things like marriage prohibitions, which, of course, the classic line is, you know, that you oblige more than you prohibit. It's really just this impulse to have more exogamous and outgroup sort of relations. You know, I was even reading some of the older Marxist anthropology on this, like Claude Maisieux, and he talks about how, you know, there's often a prohibition of internal clan consumption of meat for the hunt, where, you know, the hunter themself don't get to eat the thing that they capture.

John Protevi:Or at least they don't get to distribute it.

Andrew Culp:Sure. Yeah. And so there are all these interesting elements that I think that the mainstream account just doesn't even look at. And so because you're able to work on these multiple registers, I think that it's bringing in a much more complicated picture than many of them are able to do. And so we get to something like, I don't know, Berserker or Esprit de Corre.

Andrew Culp:Do you wanna talk about them? Because I think they're such important figures.

John Protevi:Yeah, yeah. No, so the Berserker has fascinated me for a long time. It's a multiplicity. I think in my reading of the anthropological literature, following some of the military science stuff that I've read, it does seem to be difficult except for a very small percentage of cold blooded killers to kill at close range, hand to hand and in cold blood. So for militaries to increase the ability of their fighters to engage in mortal combat have to find ways to break the one on one and have group solidarity, have to find ways to break the distance.

John Protevi:So spears are easier than knives, which are easier than hands, and on and on to the point where you just press a button. There's a very interesting turnaround with drone pilots because they don't have a killer be killed excuse, and yet they can see close-up their victims.

Andrew Culp:And this is deterritorialization, right? In the same way in which Delos says, Okay, when humans or actually pre humans stop walking on all fours, they have their hands and suddenly they start using technology. And so each one of these is a sort of de territorialization.

John Protevi:Yeah, but you get these twists and turns. The other thing then, you have to have distance, you have to have group solidarity, you end up with a lot of dehumanization, and then you end up with ways to incite rage or the appropriate level of rage. So for a hand to hand open field skirmishing, a berserker rage is very effective as the Vikings showed, right? You've so blown up your system that you're just tapping into a mammalian prey reaction. Predators are cold compared to berserkers.

John Protevi:Berserkers work themselves into a way in which they become prey so that they're lashing out, cornered prey, so they lash out at anything that's close to them. That's not a predator thing, they're cool, calm and collected. We could go back and reread each of the kills in the Iliad to see who was a berserker and who was a predator. The twist, though, comes, you know, in modern warfare, especially in the American imperial regime of violence, you don't want berserkers. They're identified and weeded out as early as possible.

John Protevi:The famous SEAL Team Six, you did not want any berserkers in that because you had to be cool and collected and follow the checklist. So berserkers are, again, it's a multiplicity. They're not good in all forms of warfare, but they are good in some forms of warfare. And the danger is they could get triggered even when you have a highly trained military person in the imperial regime of violence. So I do do a case study of this guy in Afghanistan, Robert Bales, who had a berserker reaction and killed a bunch of villagers.

John Protevi:And it created a scandal because we were supposed to do hearts and minds and counterinsurgency and all sorts of things that doesn't fit with berserking. Then the other side, so the esprit de corps was close to my heart. I wanted to do something about sports after forty years of being a philosopher. So I looked at a wonderful goal in the twenty eleven Women's World Cup when Megan Rapinoe crossed the ball to Abby Wambach and they scored a wonderful goal after 120 of awesome exertion. So when I look at what was not necessarily the escape from subjectivity, but the way in which the joint effort also produces a non utilitarian joy.

John Protevi:So to go back to chapter one, there is a way in which you can give an adaptationist reading of joy that people who seem happy will attract more mates. But that, I think, is kind of a third party observation. So when you're together with people in a second person relationship, you have a shared joy in the efforts that you're expending in the training and in the game. Sports people often, almost always say, The thing I miss about being a retired athlete is the camaraderie, the shared exertion of training. It's also fun to connect with somebody and make the pass that enables them to score.

John Protevi:You're supporting their relational autonomy. I have to make my own decision that enables you to make your own decisions. But the pass is what links the two players together. So you have to give the ball up. I mean, Messi and Maradona were good enough to dribble the whole length of the field.

John Protevi:Everyone else has to pass. The pass constitutes the passer and the receiver. It's the medium that creates the end points. That's the trans individuation bit. That was not quite self indulgent, but for me to write that sports chapter because it's been a huge part of my life.

John Protevi:And I was really glad to be able to bring some philosophy to bear on it.

Andrew Culp:Absolutely. Yeah. And I know sports is such a great example, too. In some ways, it's a sublimation of conflict or even war. And so it actually fits quite well with Berserker.

Andrew Culp:And I think the interesting part about Berserker two, especially if you bring it back to DNG's sort of metaphysics, is that, you know, for them, war isn't always negative, especially when it's used as an anti state force among nonstate peoples in order to disaccumulate power. And so, you know, it's not this simple idea of just like a pacifist who's saying, you know, berserkers are this thing we need to be really worried about, but also the professionalized military. It's it becomes, you know, a really complex sort of schema, I guess. And I'm just struck that in our political moment, institutions are becoming challenged from this sort of like unrestrained, excessive politics. And that people who are professional civil servants or professional long term federal agency workers, professional military generals, it was like the incoming political officials do not have the proper constitution or they don't have the proper mood.

Andrew Culp:And, you know, we see political rallies acting like nothing that we've ever seen before. But I think you already find this in the capital invasion chapter in which you're really trying to figure out, you know, what was going on there? Actually happened? What did it look like? Doesn't fit what we usually think of as the pretty buttoned up idea of what American politics focusing on procedure and process and these voting.

Andrew Culp:And maybe there's a little lobbying going on or something, but it's usually within a pretty expected regime where, you know, you can just read a couple headlines and feel like you know what's going on. But it's like the Financial Times might actually not have a better read of the situation sometimes now because things have gotten so different. You know, it's not just this like very functionalist material base anymore.

John Protevi:I mean, in one sense, it's going back to canes and animal spirits and the stock market is an emotional weather report to kind of mishmash Tom Waits in there. I might be one of the few people who have put Tom Waits and John Maynard Keynes in the same sentence. One of the things that certainly has come back to Duluth and Guattari, they talk about the voluptuous waves of libidinal investment that flow across the stock market. One of the ones in which they say that even the most disadvantaged creature gets a thrill at the waves of capital that are moving around the planet, which is kind of true because I remember before I even had any investments, feeling good when the TV news would say, hey, the stock market's up. Side note, of the greatest tricks of capitalism is to make professionals dependent upon the stock market for their retirement.

John Protevi:I know a lot more about investments now than I ever thought I would have to. Now COVID, yes, I think that those things come together because of debt and the way in which picking up a really nice book by Lisa Atkins called The Time of Money, she emphasizes now that people really are working, not paycheck to paycheck because they don't consume their paycheck, they're working in order to have a paycheck that they can then present as collateral for credit, which they actually live on the credit. So companies aren't interested in you paying off your bill every month, they want the ongoing debt. So that connects back to debt as to Luzincottari's main thing with debt in primitive society debt to the emperor, debt to capitalism, this is a refinement of that. So we are responsible then for financing our own lives through taking on debt.

John Protevi:And then we were made responsible for making our own virus risk assessments. So the one particular case that I looked at, a woman named Shabanta White Ballard, but she had the balance going to work in a nursing home full of COVID patients, her viral risk with her financial risk. If she didn't have the paycheck that enables her to pay off the minimum amount to keep her credit running, then there would have been a financial catastrophe for her house. And so that was a double bind and I tried to look at what in cognitive science is called the predictive brain thesis or the predictive processing whereby we're constantly making predictions and then sensory information is a reduction in the error of the prediction that we make. And that is said to save us the time and effort by making these predictions of getting real world feedback.

John Protevi:You can run a hypothetical. When you're in a no win situation you're caught in a loop of predicting a future that you cannot possibly get out of, right? Because it's a double bond. And that itself has a deleterious wearing physiological effects because one of the ways in which that actually works is there is a number of neurotransmitters that lower the synapse levels so you can think faster and harder but that actually wears you out. Especially in at least picking up the thesis of weathering by Arlene Geronimus who talks about what's called the telomere, telomere which is the end of your chromosomes and each time you have a cell division it protects the interior coating part of the chromosome.

John Protevi:That gets worn down and there is an accelerated wearing down or an accelerated aging her claim is for people in racialized and gendered subject positions in American society. So it may have been the case that this person who was a person of color, a woman of color in her 40s, may have already been affected by American racism to the point where physiologically her resistance might have been lessened but it's impossible to know what the length of your telomeres are. You can't reflect on that so that doesn't really feed into her calculations. So you end up in this kind of ruminating state, constantly going over the scenarios, do I have enough risk, what am I risking by going to work, what am I risking by not having enough to pay my debts and there's no wind for that and that itself wears you out. So that was kind of horrible double bind that I tried to see that she and many other people who were deemed essential workers either had to go to work or risk losing their jobs.

Andrew Culp:And that's one of the great shames of the American way of life and the health care system in particular, that, you know, we get a pretty consistent number, like between 1998 and 2020, there are over a million what they call excess deaths of African Americans due to a variety of factors around inadequate health care access and other really unfortunate structural causes.

John Protevi:Yeah, I mean, it's one of the things I really appreciate in your work. You do mention and talk to Liz about the shame at being human that Lewis and Pozzare talked about in What is Philosophy?

Andrew Culp:And, you know, if I'm remembering correctly, it's a reference to Primo Levi on the sort of shame of being a survivor of a great catastrophe like the camps and the Holocaust. And, you know, there are all kinds of catastrophes we've lived through since that we have to come to grips with the fact that we've survived, but maybe for reasons that weren't available to others and that that's a deep social question. I'm also reminded of two references. There's these very brief and cryptic references to the work of De Bruinhof in Doles and Gottari's work about the function of money. And I think it's been republished by Verso recently.

Andrew Culp:And while it's not exactly the same, I think it's very close to this finance and monetary credit system that you were talking about, where it's not even people's salary that is most significant. They're living off money and credit instead.

John Protevi:Well, there's one person I would mention here. I do not think he's published too much in English, but it's a French philosopher named Quentin Bader. He has a magnificent 800 page French thesis, PhD thesis, on Dulos and Guattari's use of social science. So he's a real expert on all three sections of Auntie Oedipus and the anthropological and economic economists that they use.

Andrew Culp:His book review of James E. Scott's Against the Grain is really excellent.

John Protevi:Yeah. Yeah. So let's come back to the statification thing if we could. I do try to look at what they say about capture, which is the way in which a society has to equal out, this is the imperial society, to equal out heterogeneous activities as labor, has to equal out land productivity as rent and as to equal out exchange capacities as money and tax. So this is a whole complicated thing there.

John Protevi:But that presupposes a primary violence of what Marx calls primitive accumulation which dualism could generalize to say that whenever there's capture, whenever there's a state that imposes its form of life on non state peoples there's going to be primitive accumulation and that's a prior violence. So that connects up with Benjamin and the divine violence stuff and also Derrida. But what I always wanted to see in both of those is that as soon as there's a state, there's people running from the state and then that's the Marinaj and that's one of Scott's things. So that makes it really complicated multiplicity because geography has to figure in. How close are you to the imperial center?

John Protevi:That means it's less costly for the imperial center to send its tax collectors and its armies. The further you are away, not just in distance but the closer you are to the hills, that means it's more difficult for state pursuing troops or infantry or cavalry to follow you. So the old advice of run for the hills is absolutely literally true. So the twist that brings the two things together I think is that the Maroons in establishing themselves in a place close to the state because they're not anti state but they want an independence from the state so that they can pry upon the state if they need to, or trade with the state, or even have a treaty with the state. But they have to do that in such a way that it would impose an unacceptable cost on the pursuers, the state pursuers, to actually come in and bring them back.

John Protevi:The epigraph for the Marinage chapter is from the American black radical George Jackson. I may be running, but all the while I'll be looking for a stick, a defensible position, which those in Guzzari mangles slightly by saying I'll be looking for a gun. That's because of the translation, the French translation of the church section. So the final turn of the thing is that sometimes Maroons I think might themselves come back and conquer the state and stay in the state. So in Toluca Quartari's Antioppus they make a lot about Nietzsche's line about, they come as if from nowhere, they're too hostile and foreign even to be hated, they arrive as with lightning and take over the state.

John Protevi:I don't see why that couldn't also be Maroons who've grown up, honed their fighting skills, lived a non state life and then found the weakness in the state that they're attacking in order to be free and thought, well, why don't we just stay and ourselves become state form, become the state form except we'll be at the top, not our ancestors at the bottom who ran away, but we'll come back and do that. There's very little evidence of that kind of thing but I think it fits the framework that the Lewis and Quechua lay out and it does connect with what Scott said about the non state peoples who are in constant interaction with the state. And in fact, both of them are co dependent. The state needs the non state people for the raw materials and the jewels and the slaves that the non state people can capture and bring into the state as well. So it's quite a big multiplicity, I try to distinguish different regimes of violence.

John Protevi:The primary regime of violence of statification which installs capture such that theft becomes a crime against the state and the police will go after that but that's only after the primitive accumulation or the primary violence. And the Maroons have their own form of regime of violence. They're very unforgiving of deserters. They're also a little suspicious of people that they captured in one of their periodic raids and would capture them. They needed to go through a seasoning process or an acclimation process of living free for several years before they would be trusted.

John Protevi:They were kept as kind of household servants whereas they were very accepting of people who actually ran away themselves. So that was the kind of proof that you wanted to live free was that you got there to the Maroon community whereas if you had to go in and you had to be taken there on a raid, you had to prove yourself. So that's a regime of violence there.

Andrew Culp:Yeah. I mean, to talk about that final turn that you mentioned in which a non state people might actually return to settle the state. If you do the very long history of state formation, this is actually common in a number of instances. To use one that's close to, you know, the Luzengaturi's heart, The city state of Ur in the Sumerian empire, we're thinking circa about 2,000 BC, but it had been around for maybe about fifteen hundred years prior to that as well. There's the final fall of Sumer, and there's even a lament for it and everything.

Andrew Culp:And they'd fought off some nomadic people from the what is now the Southeastern Mountains of Turkey where they got their wood and cedar. But the people from the Northeast that eventually, helped contribute to their nomads, who are the Martu, themselves were a nomadic raiding people. And after you have the fall of Ur, in part they're the the Elamites too who are, like, from Iran. But, once the Martu, like, conquered the the cities, they settle them and live in them for themselves for quite a while and then become sort of institutionalized. Or, like, there's a whole series of rulers in the ancient Egyptian empire who were from foreign regions.

Andrew Culp:They conquer, And instead of imposing their own culture on it, they assimilate into Egyptian culture. So there you know, all these, like, fun not fun. Fun's not the right word here. There are all these, unexpected and curious examples. And I think that that's what's so important about returning this material because there's such a hegemony of a modern and liberal jurisprudence approach to how social and political change happens.

Andrew Culp:And it imagines that it happens by rotating who's in office and gets to set policy. Occasionally, it's by some unexpected people from below seizing the institutions and then and turning it to their advantage. But the maroon gives us a completely different schema for political transformation, and that it's one first of just subtraction or elimination. You know? It sort of starves the beast as it were.

Andrew Culp:But then you're right. I mean, it's not always normatively good. People can reestablish a state and perhaps even a more brutal one in the process. The other thing about this different political schema is, you know, D and G are sort of ironically playing on Henry Louis Morgan's, anthropology that was then, you know, obviously quite complicated, way too evolutionary in its path, deterministic. And then when Engels got ahold of it, under the influence of social Darwinism, creates a very challenging framework that its basic ideas that, you know, there's a history to the creation of the family, private property and the states.

Andrew Culp:And then all three of those will have to be challenged and undermined for a successful socialist or even ideally, you know, communist transformation. But then all of the methodology behind it has been undermined since. And so I think you take a really helpful path that just dispenses with trying to have a tortured reworking of it and finds a much more productive political avenue.

John Protevi:Well, thank you. That's yeah, I mean, the first thing we have to do is get away from any, progressivism, depending on how horrific you paint the state of nature. In Hobbes or merely just a bad business environment, as with Locke, the only rational move really is to join civil society is to sign the social contract and either delegate to the sovereign or become part of the sovereign or at least have a limited sovereign. We know all the permutations of that. But that neglects the fact that specifically slaves are encasted as the outside within the social contract, right?

John Protevi:They're not covered, they're not citizens, they don't sign the contract, but they're casted within it as the outside that could be killed with impunity then we could move to the necropolitics and bembe and a whole bunch of other stuff like that. So of course the slave wants to escape. The only rational move for an enslaved person is to flee that territory governed by that social contract and run for the hills. You just have to use the economic principle of the revealed preferences to see that when people run away from the state, they're showing their position within the so called social contract. It's better in the woods.

John Protevi:There's a wonderful article by Daniel Lubin called Hobbesian Slavery in which he talks about the way in which the right to rebellion is one of the inalienable rights if you're put in a position in which your life is not worth living. They are still in a state of nature hence all means are open to them of recourse so that an enslaved person cannot commit a murder because they're in the state of nature and murder is only a crime in a civil society. So Hobbes along this reading is really very interesting. Enslaved people cannot murder their captors. They can kill them in order to escape but because they're not part of the social contract, they're not bound by the civil society because they never agreed to it and hence, you know, so that's a regime of violence that includes killing, but not murder.

John Protevi:So that's one of the things when use the big framework of regime of violence. I'm not a bad Rousseau reader in the sense that people think that Rousseau said that the state of nature was nice or something. She doesn't really say that. The first part of the discourse on inequality is probably a hypothetical of what would have been necessary in order to produce human beings and human beings only appear in the beginning of the second part of the discourse on inequality and there there's plenty of violence there. But it's just as any social formation must channel its desiring production, so must any socius or any social formation must channel its violence.

John Protevi:Within a slave holding society you are granted impunity in rendering violent acts against slaves and the thing that makes the whole system tremble is the slave who kills the master. So it's regulated in that way as part of what provokes response. Having a regime of violence doesn't mean that it's a free for all. You can't have free for alls. Any social formation has to regulate.

John Protevi:Desiring production, which you can cash out in terms of who gets to hook up with who, who gets to eat what, who gets free time in order to make things, who has to owe a certain amount to somebody else and who gets to hit who.

Andrew Culp:And, you know, speaking of insult and injury, one of my favorite dimensions of non state people's lives too is the organized use of insult or, you know, heckling in order to disaccumulate power as well. Someone is getting a little too powerful or a little too independent or something like that, then, boy, do they get, all the insults heaped on them until they're taken down a few, notches in the in the the social ranking. So maybe thinking about, you know, the thing that makes the system tremble in a slave owning society is, you know, the slave who strikes back, and that's why it's so deeply regulated. It also makes me think, you know, the way to get away with it is to do it and then disappear or have this basis outside of it, which, you know, at least to me, brings back the the darkness of the dark deliz or the unintelligible or the space of the outside. You know?

Andrew Culp:But for you, maybe it leads us to the conclusion on the joyousness as well. So maybe we can, have you give your final case for the joy, which, by the way, just if, you know, people are listening at home, I always say that it's an asymmetric contrast from the joy. It's not meant to be some sort of complete opposite. You know, there is a space for joy in the darkness, maybe even a joy division. But, you know, John, give us your case for the joy.

John Protevi:Well, I mean, I set the whole thing up by saying it's ambivalent. There's all sorts of passive joy. I do try to run this when there was a line that you cannot have active sadness, right, because an active relationship is going to build up your power. Your power means your ability to be affected and to affect others. So insofar as you understand your contribution to an encounter, that is an amplification of, it's an expression of your power and amplification of your affective spread and that cannot be sad as he says.

John Protevi:But you can have passive joy and that's the danger of being swept away by the mob or whatever. So while I don't accept Le Bon's phobia about all crowds and all mobs. I am worried about crowds and mobs.

Andrew Culp:So in conclusion, tie this to anti fascism. So maybe this is the culminating point on that too.

John Protevi:So I've always been really struck by Foucault's preface to the English translation published by University of Minnesota Press of Anti Oedipus. And there he has some wonderful things warning to, we must defeat the desires described as the fascism in us all, our hearts, in our everyday behavior, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us. Foucault continues by saying, Be multiple, not totalizing, never terrorize your readers, never claim to have found the pure order, be joyous, do not think one has to be sad to be militant, do not become enamored of power. I do then distinguish active joy from passive joy in the spinacist connection. So the passive joy comes from being taken up outside yourself into the mob transfixed by the leader.

John Protevi:But active joy is in a network situation in which you turn on someone who enables them to turn on other people. So let me read this here. I propose an ethical standard. Does the encounter produce repeatable, mutually active joyous affect in enacting positive care and cooperation? And then I do end up saying something like, we're at a turning point, an inflection point with regard to the challenge to liberalism posed by the worldwide turn to fascism and the question of whether we can reform liberalism in a democratic socialist manner, quickly enough and radically enough to enable us to deal with climate change, mass incarceration, debt servitude, both of the third world and of the mass of people in The United States, or do we have to institute a revolution regime of violence against the fascism that we see a raid against us?

John Protevi:That's not up for me to decide, that will be decided in the streets or if we last long enough in 2026 and 2028 in the next two presidential elections. But we're not going to get there as long as the Harris, Biden, Obama wing of the Democratic party insists on being more afraid of losing their donors than of losing an election. So final thing, American regime of violence has been hit with a lightning bolt by Luigi Magione, who assassinated in a classic propaganda of the deed direct action right from 1900. He shot a CEO on the streets of Manhattan, is that going to shock and galvanize the American people enough to pressure the democratic party? I kind of doubt it because everything we've seen so far has either been kind of Alexandria Ocasio Cortez saying something like, you know, this is not to justify the murder, but I understand where he's coming from, which is fine.

John Protevi:You have to distinguish explanation from justification. But that was an event whose reverberations through the American political system and its ability to capture those events and encapsulate them and render them neutral or whether it will reverberate around. But there's a lot of scared establishment folks. It's a structure, You can kill the CEO, there's a new CEO in place but it's not to justify it but it has to be explained and in order to understand I do think you have to have at least some ability to enter the world of the perpetrator of the deed in order to find out his motivations.

Andrew Culp:Yeah, right before you ended, I was thinking maybe we're in a Timothy Leary or Malcolm X situation and either turn on, tune in, drop out, or by any means necessary. But now I'm hearing echoes of Lucy Gonzales Parsons, whose husband was executed as one of the Haymarket martyrs in Chicago. Her famous words, let every dirty, lousy tramp arm himself with a revolver and knife and lay in wait in the steps of the palaces of the rich and stab or shoot the owners as they come out. You know, maybe it's not 1887 again, but it is a point in which this new Gilded Age, there's a new version of fascism, and something's gonna change and hopefully for the better.

John Protevi:Yep. Yeah. Yep.

Andrew Culp:Well, thanks, John. I mean, your book's gonna be a wonderful resource in helping think about this moment, other ones in the past, but hopefully some new and more interesting or at least creative anti fascist ones in the future. And I invite everyone to please check out the book.

John Protevi:Thank you very much, Andrew. And no, I'm looking forward to the conversations that I hope will be sparked by this book.

Andrew Culp:Yeah. Thanks, Maggie and everyone else at University of Minnesota Press for making this possible and all the wonderful work that they do.

John Protevi:Yes, 100%. We can't do it without a lot of help.

Narrator:This has been a University of Minnesota Press production. The book Regimes of Violence toward a political anthropology by John Protivi is available from University of Minnesota Press. Thank you for listening.