“I want to be a living work of art”: On the Marchesa Luisa Casati

She gained a certain form of confidence and fearlessness that allowed her to express herself on the deepest level.

Francesca Granata:She was born into an upper middle class Milanese family. The standards, not only of beauty, but of acceptable femininity, was quite restricted.

Valerie Steele:She goes through a wide variety of very theatrical fashion that teeters on the edge between couture and costume.

Joan Rosasco:She was an anachronism. She seemed to belong to the world of late romanticism.

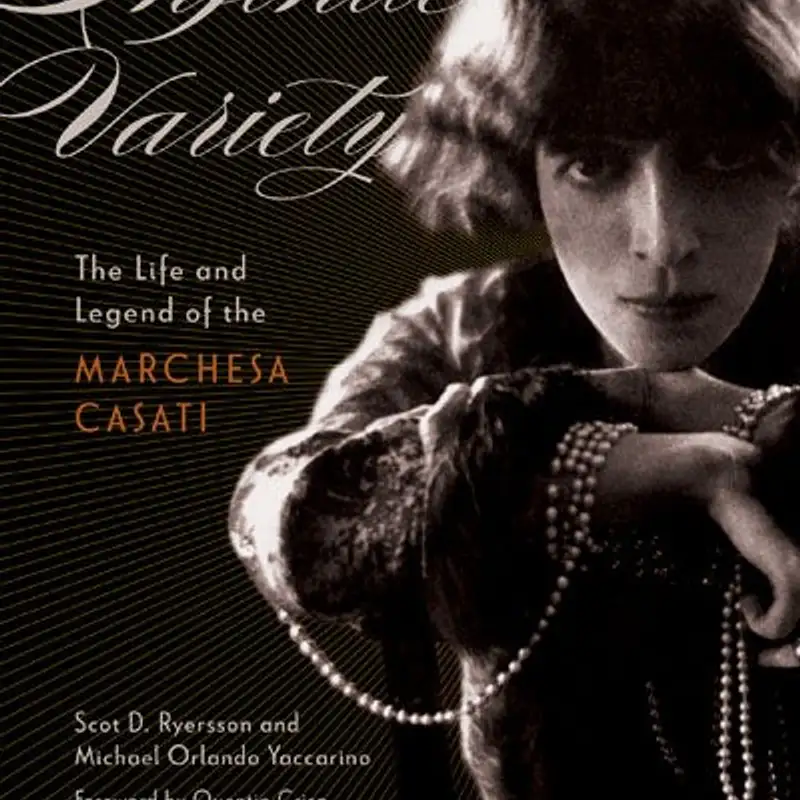

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Greetings, everyone. We're here today to celebrate the twenty fifth anniversary of the original publication of Infinite Variety, the life and legend of the Marchesa Casati, the first full length comprehensive biography of this amazing woman who lived from 1881 to 1957. We're going to begin with introducing ourselves. So I'm going to start with a brief biographical overview of my coauthor, Scott d Ryerson. Scott d Ryerson was the author of numerous critiques and essays on film and literature.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:He published interviews with author Anne Rice, actress Diana Rigg, Poirot actor David Suchet, Marple actress Joan Hixson, and film director Tim Burton among many others, as well as an analysis of the little known supernatural fiction of Agatha Christie. He also penned the novellas Poisoned Ivy, The Arsenic Flower, Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know, and the one PFR nominated short story Summer's Lease. His poetry appeared in The New Yorker. As an artist, got trained at London's Chelsea School Of Art And Design before entering the field of motion picture advertising. Throughout a thirty year career, he designed multi award winning graphics for numerous Hollywood and international films, including the silence of the lambs, ghost, the doors, the changeling, white mischief, the hunt for red October, witness, another country, and evil under the sun.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Recipient of two art directors of London awards, his work continues to be voted among the top of several greatest film posters of all time lists. His pen and ink illustrations appeared in publications worldwide. Scott created and exhibited numerous arcana facts, a term for his one of a kind mixed media assemblage and collage pieces, which explore his artistic obsession with the arcane and phantasmagorical. As for myself, I have written on genre films and their creators, unconventional historical figures, and the occult. And I should have noted my name is Michael Orlando Yaccarino.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:I'm a film studies graduate from New York University's Tisch School of the Arts, which included an extended internship at the Film Studies Center of the Museum of Modern Art. My critical writings and interviews have championed world fringe cinema for decades. Having researched, practiced, taught, and written about the tarot for many years, I am the author of Heart Vision, Tarot's Inner Path, which Scott illustrated. Together, Scott and I are the coauthors of Infinite Variety, the life and legend of the Marchesa Casati, and a one woman play based upon it. The decadent fairy tale, The Princess of Wax, A Cruel Tale, and the art book, The Marchesa Cassati Portraits of a Muse.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:We also co edited Spectral Haunts and Phantom Lovers, an audiobook collection of British ghost stories. Based in The United States, the Casati Archives is the world's only data source and image bank devoted to preserving the artistic and cultural legacy of the Marchesa Luisa Casati. Scott and I founded it twenty five years ago in 1999 upon the original publication of Infinite Variety. It is the result of ongoing international research and collecting. In addition to a wealth of original materials, books, and ephemera, this ever growing library contains artwork reproductions and photographs of and inspired by the Marchesa Casati.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:The Casati Archives provides images and information for writers, researchers, and publishers worldwide, as well as consulting services for the world's leading museums, galleries, and private collectors. It would be terribly remiss not to fully recognize infinite variety's provenance, to use an art term. And this most definitively belongs to Scott d Ryerson, For it was Scott's original in person viewing of Augustus John's celebrated 1919 portrait of Casati many decades ago, which first ignited a curiosity within him about this extraordinary being, which remained inexhaustible until his passing earlier this year. Indeed, he likened this catalytic moment to an actual visceral encounter. Scott's tireless research is wholly responsible for the book's proven accuracy and remarkable comprehensiveness.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Indeed, every subsequent edition of the biography around the world contains research gems most currently uncovered at the time of its publication. How wonderful then that Scott was here for Infinite Variety's two thousand twenty four quarter century milestone that is twenty five years of our thirty eight years together as life partners. And now I would like to introduce our other speakers today, and we can begin with Valerie Steele.

Valerie Steele:Hi. I'm Valerie Steele. I'm director and chief curator of the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, where I've organized more than two dozen exhibitions since 1997, including The Corset Fashioning the Body, Gothic Dark Glamour, and A Queer History of Fashion. I am also the author or editor of more than 25 books, including Paris Fashion, Fetish, Fashion, Sex, and Power, and Fashion Designers a to z, the collection of the museum at FIT. My books have been translated into Chinese, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, and soon also Japanese, and Spanish.

Valerie Steele:I'm also founder and editor of Fashion Theory, the Journal of Dress, Body, and Culture, which is the first peer reviewed scholarly journal in fashion studies.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Thank you so much, Valerie. Joan t Rosasco.

Joan Rosasco:I'm Joan Rosasco. My field of interest has always been, European art and culture, particularly French. I taught French literature at Smith College and, at Columbia University, some courses also at NYU. My publications have mostly been on the Belle Epoque, My book on was published by Nise in Paris, and I also have various other publications. I also have worked with exhibitions international to organize traveling art exhibitions and notably, the jewels of Lalique in 1998.

Joan Rosasco:And it was, in association with that project that I encountered infinite variety. I was reading it on the airplane going to Paris to be with Madame, Burynhamaire, curator of the exhibition, and saw the photograph of Luisa Casati wearing the lolly crown that he had, created for Sarah Bernhardt in Theodora. So for me, that was the way into the subject. That's when I met Scott and Michael, and we've been friends ever since.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Thank you so much, Joan. And finally, Francesca Granato.

Francesca Granata:Hello, everyone. My name is Francesca Granata, and I'm associate professor of fashion studies in the School of Art and Design History and Theory at Parsons School of Design. My research, centers on modern contemporary visual and material culture with a focus on fashion history and theory, gender and performance studies. I have written several publication, that look at the intersection of fashion and performance, experimental fashion, performance art, and the grotesque body. My book from Bloomsbury two thousand seventeen addresses these issues, and I've also edited two books.

Francesca Granata:One is fashion criticism and anthology, also from Bloomsbury, And, the other one is fashion projects, fifteen years of fashion dialogue, which is the collected work from a journal, nonprofit journal I ran from 02/2005 to 02/2025, called fashion projects.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:And, Francesca, we should mention, of course, that you are responsible for the lovely and insightful new forward, to infinite variety that have been added in the University of Minnesota Press's two thousand seventeen republication of the biography. So you are represented in the the book itself, as well. Thank you, everyone. And now as perhaps a way into our fabulous subject, I'm going to read an excerpted version of Infinite Variety's introduction. And after Joan's flawless French terms, I'm I'm going to ask your forgiveness if I butcher a few that are included in this introduction as I read.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:I want to be a living work of art. These are among the only words spoken by the Marchesa Olisa Casati that have been documented. For the first three decades of the twentieth century, the Marchesa Casati was the brightest star of the European hautemand. Artists painted and sculpted her, poets praised her strange beauty, and couturiers fought for her patronage. She'd even become the notorious fictional heroine of more than one author's risque, Romana Clay.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:She journeyed wherever her fancy took her, Venice, Rome, Paris, Capri, collecting palaces and a menagerie of exotic animals, and she spent fortunes on lavish parties. She astonished Gabriela Dinunzio, fascinated Sergei Diaghilev, frightened Artur Rubinstein, and intimidated T. E. Lawrence. Graham Bakst, Paul Poiret, Mariano Fortuny, and Erte dressed her.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:She dined with Picasso, hosted parties where Voslaw Nijinsky invited Isadora Duncan to dance, became the Italian futurist muse, and helped conjure up an elaborate marionette show with music by Maurice Ravel. Everywhere she went, she set trends, inspired genius, and astounded even the most jaded members of the aristocracy. Louisa Kisaki's egocentrism is both undeniable and linked inextricably to historical significance. It was specifically the Marchesa's mania for continual transformation that propelled her quest for geniuses to document this lifelong process. Unlike the typical society patron, Casati was fearless in becoming an eager accomplice to the talent she supported.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:For them, she became a tangible and effective promotion of their radical artistic experiments. It seems a curious injustice then that one of the most portrayed women in history has been so little known. Even though numerous references to Casati appear in many art, history, and fashion books, no comprehensive full length biography of her has been previously published. Such is history's fate for a life that can be too easily dismissed as idle, hedonistic, and thoroughly excessive. Our purpose in writing the biography is to accurately document for the first time both the life and legend of this singular woman.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:In presenting this, our hope is to ensure the Marchesa Casati's significant place and the artistic and cultural heritage of the twentieth century and its continuation into this millennium. So we have a wide variety of topics to talk about because Kasafi's life touched so many areas of art, culture, history, more specifically, women's studies, fashion and art and their transformative abilities for both the the viewer and in the pace of fashion, and the wearer. And we do have a you know, today, amongst our speakers, of course, we you know, all three of them have a tremendous, and in-depth knowledge of, costume, fashion, and how they play very important roles in the cultural landscape of the time in which the times in which we are talking and beyond that. You know, Casati lived a a relatively long life, which which spanned from the Belle Epoque through to a good portion of the twentieth century. And for someone to remain so remarkably vital and inspirational is is quite rare.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:What I thought we might begin with as a as a point of departure, maybe we could return to Joan's comment about seeing that image of the Marchesa Casati mimicking, if you will, of some famous theatrical still photographs of Sarah Bernhardt as Empress Theodora. Why don't you speak for a moment, Joan, about that?

Joan Rosasco:Yes. I was so surprised to see the picture of Sarah that Casati was clearly basing, her costume for a ball in '24. It was a costume ball in Rome, and she was dressed as Theodora as played by Sarah Bernhardt. And I thought Bernhardt then was the most famous woman in the world, the most photographed, the most painted. If you saw the large exhibition at the Petit Palais recently, you saw that Sarah Bernhardt really was famous everywhere.

Joan Rosasco:Her most famous role was as Theodora, the Byzantine empress. So I found this picture in the book, and I noticed that it was the crown that Lalique had designed for Sarah, but it wasn't known if this crown had ever been made because there was no evidence for it in the many, many photographs of Sarah in the role of Theodora. She preferred a, crown that was based on the mosaic Ravenna. Looks more like a Kokosnik, and that crown still exists. It's in the Musee Galliera.

Joan Rosasco:But this one was only the little painting by Lalique that served as the cover of the program in 1902. So it was possible that this was actually the crown, that Sarah didn't wear and was only, in the painting and the painting that clearly Casati was posing as.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Thank you. And what what I wanna take away from what you were saying, Joan, when you mentioned that at the time, you know, Sarah Bernhardt was a world renowned superstar. So when we see perhaps the Marchesa finding a kinship in her and really slavishly recreating that image, I think that that may show in a way her at the start of her transformative process of perhaps looking outward and reaching out towards what was popular at that time and making it her own. But as she continued to go on and evolve, I think that she then gained a certain form of confidence and fearlessness that allowed her to not so much mimic others, but to express herself on the deepest level. And I'd like to use that as perhaps, Franchesca, you know, you have written so much about unconventional beauty, even bordering on the grotesque.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:And I don't wanna jump too far ahead, but if we do go through the Marchesa's visual aesthetic over the course of years and decades, it does become that much more idiosyncratic, that much more strangely beautiful, and that much more uniquely her own. The Marchesa started out her life as a very awkward adolescent, a not very confident about her own looks and her fitting into the conventions of the time. And that as she gained agency, that changed.

Francesca Granata:Yes. It's interesting. So she was born into an upper middle class, a Milanese family. And so the standards, not only of beauty, but of acceptable femininity for that demographics was quite restrictive. And she was not traditionally beautiful for the centers of the time.

Francesca Granata:And I think she eventually, as you said, started to, kind of cultivate her own persona, her own look. I mean, when I think of Casati in contemporary time, I almost think of her as, like, a, club figure or somebody who is really just really into performing the self in a very at least incredible, also very creative, way. I mean, she was her own work of art as your book makes clear. As a a work evolved and also participating all these, avant garde spaces in Europe, I think she kind of became more and more daring in, her looks or makeup or clothing. She went from working with couturier to going to costume design because the couturier's work was not, fantastical enough.

Francesca Granata:And so, yes, I think she embraced almost this kind of ugly beauty that is questioning what is really beautiful, what was really beautiful in, Europe at the time. I think it was probably also a reaction to the way she was perceived earlier on as not really fitting in.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Valerie, maybe this would be an opportunity for our listeners to try to put her shock value in the context historically of what was happening in fashion at at that time.

Valerie Steele:Right. Well, as you look at her life, she goes through a wide variety of fantastic fashions. And as Franchesca said, she starts out with couture, avant garde couture, you know, Fortuny, Poire, and increasingly moves towards costume, whether the costumes, minaret, or box costumes, very much sort of ballet rooste type costuming. All of which are pushing at the edge of the avant garde. So it's a lot of fantasy imagery, orientalist fantasies about women in the harem and bloodthirsty sultans and the way she wrapped snakes around herself or walked with leopards.

Valerie Steele:The stories that she would appear in Saint Mark's Plaza dressed in a cape, leading a leopard on a leash, and under the cape would be naked. All of these are incredibly exhibitionistic and exaggerated versions of self fashioning. Actually, my favorite thing though that I rediscovered rereading the book again last night was what you and Scott described as one of her more restrained fashion, style when she went out on the street one day wearing a black velvet V and A dress, a tiger skin top hat, and one black eye patch. And I just thought, oh my god. That's so fabulous.

Valerie Steele:Galliano would have died for a look like that. That's so amazing. It's so perfect in terms of contemporary avant garde theatrical fashion. And I think you can put her in that whole history from Poiret to Galliano and McQueen, a very theatrical fashion that teeters on the edge between couture and costume. You know, we'll sometimes say as a criticism.

Valerie Steele:Oh, that's too costumey. But it's like Francesca saying she's like a club kid. She's like somebody who's created these amazing look through costume, makeup, hair, all of which are exaggerated and fantastical, almost grotesque, teetering on the edge of of decadence and grotesque green.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Thank you. And, Joan, how do you feel this would translate into more of a societal because of, you know, the the the milieu in which she traveled, everyone from budding artists to political figures to nobility. Can you give us, Joan, just a sense of that type of shock and awe would be experienced by a French salon, let's say, or someone that came out of of Proust's circle?

Joan Rosasco:Well, she didn't have a conventional salon. There were so many society women. Many people in Venice that she she had a plot, so did the Curtis family at Palazzo Barbaro, Isabella Stewart Gardner was there. The process de Polignac at the Palazzo Polignac, and so on. And these women, or Madame Labon Pluvinell at Cadario, they had salon.

Joan Rosasco:They attracted writers, artists. There was conversation. She was so different. She had entertainments, but, these parties were mostly a kind of setting for her own exhibition. Her costumes, her animals, the white peacocks.

Joan Rosasco:And as you said in the beginning, I think her great attitude was that she didn't speak, that there was no message, that she remained an enigma, and still does. She seemed to put on these various masks and disguises. But what was behind the mask? It was a mystery. So she was very unlike the other social leaders, and we don't see her, very often, or at least I didn't see evidence of her in other people's salons.

Joan Rosasco:You you don't find her as a guest at someone's luncheon or dinner party. When you read people's diaries, she they talk about her, but she's, more a phenomenon. She she was unique in that sense.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Absolutely. And, you know, when Scott and I were writing the book, we wanted to present a portrait that showed as much as we could this extraordinary woman in all her shades and colors, light through dark. We really had to make a decision about not wanting to fall into pop psychologizing. I mean, one of the questions, of course, that a reader of the book would make would why did she do what she did? What was her motivation?

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:What was what did she think about? What should you know, and there's there's very, very little that survives that gives anything more than a fairly superficial insight. We can make suppositions. We could make, suggestions of what we thought, but we don't know definitively. As she even during her younger years, but especially as she became older, part of her ensemble was a veil.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:And we tried to keep that as well with the book, to keep her as an enticement, as a mystery. But maybe from each of your perspectives, we could speak just a moment on what perhaps your own insights are on why Casati did what she did, or perhaps what was her motivation. And Francesca, with your work on unconventional beauty and the bizarre and the grotesque, and when you have focused on certain figures within and outside of the of the the fashion world, have you found some kind of connectivity between some of those figures with the Marchesa? So for example, if I'm recalling correctly, Earte once comment that the Marchesa was someone that he found extremely shy, which, of course, would seem at odds with egocentrism and exhibitionism. But then again, how did that such elaborateness perhaps function psychologically speaking for someone who was at core, someone who's very private and shined?

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Have you seen that with other perpetrators of fashion crimes?

Francesca Granata:I'm not sure if I can make that connection at the top of my head. I think it's interesting how they use all these, disguise for the self and masks. Right? It reminds me of, the carnival, and it's kind of makes sense that one of the form that she used to express herself was the masked ball. To me, that is this idea of wanting to not kind of have this fixed identity, but, like, continually transforming yourself and seeking the the edge of different identities.

Francesca Granata:I think it's what's I found really interesting about the Marquise Casati is that she foreshadowed a lot of play with gender that we have seen in the postwar years much more coming to the fore and, definitely in the last twenty, thirty years. And, I keep returning to club culture and these figures like Lee Bowery, somebody that, like a Kasati, makes this kind of confusion confuses and questions the difference between reality and make believe. Right? Where is the reality of Kasati when she's always in costume? She's always performing.

Francesca Granata:So she's almost questioning the idea of an authentic self that exists from which everything else comes out of. So I think that's what's, to me, was very fascinating about Damarcheita Casati and seemed really ahead of her time also in in the way that she she really lived her life between categories.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:And, Valerie, in the great gallery of significant fashion figures, the rule breakers, the iconoclasts. Do you see an affinity between her and any of them in particular, and how might she differ from them? What were some of their similarities, and what made her uniquely herself?

Valerie Steele:Well, what strikes me about her very powerfully is her exhibitionism. Thinking about it, it reminded me quite a bit of the Comtesse du Glafout, Montesquieu's, cousin, who also was someone who wanted to be sort of gazed at by a multitude of people and to sort of drink in their gaze. And that made her feel alive in a sense and and energized through that vision of them looking at her. And it seems to me that with both of them, there was not the kind of idea of male exhibitionism, like, look at my penis or look at my nakedness, but rather a more almost infantile, look at me, pay attention to me, so a demand so that she wouldn't disappear, that people would see her and she would feel reassured and happy by that gaze as though the gaze kept her alive. Almost like Tinkerbell, you know, and Peter Pan is like, believe in me, and then you'll keep me alive.

Valerie Steele:And so something very existential and desperate about that exhibitionism. But also as Franchesca said, the fact that look at me because I'm constantly changing. My look is constantly changing. Also implies a kind of deliberate artifice or a veil that she keeps it's like, you'll have to keep looking at me because I'm constantly changing, and I'm I'm always new, and I'm always different. So you'll never stop being fascinated with me.

Valerie Steele:So there's also a kind of strange artificial neophilia there, which is really interesting that she wants to be a kind of an artificial woman who's transformed all the time that with the descript a kind of a changeable, renewable second skin all the time.

Joan Rosasco:And she belongs to a lineage, I think, that extends from Castiglione to Roberto Montesquiut to Cassati. And it's interesting that she comes at the last of the line, but they're all fascinated by their own images, conspire to create images of themselves. Castiglione with Pearson, the photographer, over, I think, four decades, just documenting her own looks and curating her own photoshoots, and then Roberta Montesquieu doing the same thing. I was going to say before that there's an interesting photograph of him when he was only 19. He was, asked to play the part of Zanetto in a play called Le Passant in a drawing room, performance.

Joan Rosasco:And so that was Sarah Bernhardt's first big breakthrough role in, I think, 1864. So now, much later, he went to Sarah to have her coach him in the part. And in the photograph, he is sitting on some steps wearing the costume of Zanetto, supposed to be a renaissance minstrel. And she's sitting next to him, and she's wearing the costume. And they look like mirror images.

Joan Rosasco:And I think this, fascination with your double, with the simulacra, with, of course, later the wax figures and so on. But, and Montesquieu kept all these photographs of himself from then on in albums that he called ego imago, image of myself. And then you think, am I the image? Perhaps that just means that I am an image or I am the appearance. And I think he then collected the photographs of Castiglione and as many relics of her as he could find and had a little chapel devoted to her.

Joan Rosasco:And after Casati bought his house after he died, she also had these same photographs. She too had a collection. She then had a ball in which she impersonated Castiglione. It's really a lineage. And these three personalities that were so similar in their self adulation and their desire to be represented.

Joan Rosasco:Montesquieu also commissioned many portraits of himself. He was painted by Boldini as she was. He was depicted by Troubad Scoy as, she was. And, then she moves into his house. Their psychologies are interesting to consider together.

Valerie Steele:Yes. I think that that genealogy and that idea of the doubling that she identified with Castiglione and Montesquieu's doing some of the same thing is so fascinating. And your reference to the wax figures, that she had the wax figure of herself dressed in the same clothes, it's really an amazing fascination, like an artificial double. Again, the kind of reassurance, I'm here. I'm here in spades.

Valerie Steele:I'm here in duplicate.

Francesca Granata:Yep. There is an element of our work. I think it also relates to this idea of, like, being in a constant carnival, right, where the rules and norms are lifted and when you're always in costume. But it also made our work ephemeral. Right?

Francesca Granata:And that's part of the reason these ephemerality is part of the reason, I think, where she was not as remember as she could have been until the biography and the subsequent also documentation of her work. I think it's it has to do with this ephemeral quality, not only of fashion, which was one of her means of expression, but also there was a real interest in things that that were finite. Right? She would put months and months into creating a mask ball, which in and of itself is an ephemeral kind of performative space that ends and is poorly documented.

Valerie Steele:Of course, that's true of fashion in general. So this love of self fashioning is the kind of the constant repetition of ephemeral forms. I love too finding out that she commissioned a doll of herself from Lottie Prisel, which is so amazing. That was a sort of a semiannude, quasi religious, baroque doll. That doll still exist?

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:We were in touch with a private collector who had, many, many, many of them. And, unfortunately, that person passed, and we were in touch with, an author who was working on documenting Fritzl's life and had been behind an exhibition of, on her, I believe, in Germany. I'm not sure the whereabouts of those items now. I mean, of Fritzl's collection and and the majority of Casati. I mean, we have to remember that when the Marchesa stars started misaligning during her latter years in Paris, which ended up in bankruptcy and enforced auction of her home, so much of her property was dispersed.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:So there really is not a tremendous that exists. I mean, it is a tragedy that we don't have a few costumes. I mean, there are little odds and ends here and there around the world, but there's very, very little that exists in that way. I I think it might help to just take a moment for maybe each of us to comment of how the Marchesa transcended the time period. Some of these great art patrons, society figures are very, very much more often than not linked and bounded by the time period in which they lived.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:This is not true of the Marchesa. I will begin this by saying, well, it's a reflection of the nonstop activity and curiosity of her mind, and that she was not only reaching out to being represented by such, at the time, recognized geniuses in the art world or society painters such as Baldini. But she was also very much interested in seeking out new talent. So we have, you know, the stories of her meeting with Man Ray, you know, this American photographer relocated to Paris at the beginning of his career who was very little known. The results of their photographic connection resulted in his getting many, many jobs with with high profile fashion magazines and and helping to launch his career, in a fuller way.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:So she was unhesitant to seek out the unconventional. She didn't wanna rely just on what her peers might think was desirable. So, Franchesca, we know you have to end in a few moments. If you don't mind making a few final comments on what was uniquely, perhaps from your work, bizarrely wonderful and strangely beautiful in terms of her aesthetic and perspective and point of view that has allowed her to transcend her times? And here we are now more than a hundred years after her heyday, and we're here talking about it.

Francesca Granata:Yeah. I mean, I think a lot of it is that, she was questioning traditional femininity. Right? Traditional feminine roles of our time. I mean, she was certainly scandalous for a Milanese upper bourgeois society where she came from, and she was, I mean, it sounds like she was a borderline scandalous for the avant garde.

Francesca Granata:So I think also a kind of threatening beauty, so to speak, that we we have seen, in contemporary fashion through McQueen, especially is something that's remained relevant. So this this going against, somewhat, domesticated or, yes, more reassuring beauty, but also, feminine roles is what I think kept her in her interesting and kept her relevant to into the twenty first century.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Wonderful. Thank you so much for your insights, Francesca. And, Joan, you've written and spoken about some of the great feminine beauties and female icons of the Belle Epoque, and even how there was a societal shift as the motion picture became popular, which was a massive industry in in Italy, for which, of course, D'Annunzio, one of the Marches' most illustrious lovers and comrades, the great Italian, poet, well, war hero and society figure, worked for the silent film industry. In viewing these amazing women of that time period who have not really they they they're remarkable, but they haven't broken out of that time period. Do you have any thoughts on what allowed the Marchesa to do that, or what what resulted in that?

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Was it that she was an outcast, or there was a time she no longer really cared about that?

Joan Rosasco:Well, I I feel that she was actually, an anachronism. She seemed to belong to the world of late romanticism, the world that Mario Protz describes in the romantic agony or la carne la morte e diavolo. All these themes of, the fatal woman, the, Medusa, the macabre, the occult, she personified with her dark, eyes, ringed with black coal. And she, I think, was then a model later for the silent film stars. I'm thinking, of, Musidora in Les Vampir by Folliard.

Joan Rosasco:That was, in, I think, about 1915, '19 '16. These vamps were now becoming sort of popular culture, whereas in the eighteen eighties and nineties, that had been part of symbolism, that they'd been taken very seriously. These were, Salome. I think of, Oscar Wilde and the Beardsley image of Salome. She's a terrifying apparition.

Joan Rosasco:And I think Casati was also from very much in that category until the war. And then after the war, there was such a shift in culture, and she really became anachronistic. You don't see her as part of the jazz age. And, you know, she left left Venice in 1923. Cole Porter rented the Cara Sonico in 1925, brought his American black jazz band, had a floating nightclub on the canals.

Joan Rosasco:I mean, it was a totally different culture that she really was no longer, in sync with. So I think she was the last gasp of romanticism, and she was a beautiful late flower of that movement.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Thank you so much, John. That's extremely in insightful and that she was, as you mentioned, a throwback to an earlier ideal. And, you know, I think what makes it even more fascinating now is that is that that is absolutely valid. And then because of circumstances in the and and what happened in her life as she lost her fortunes and her desire to create and recreate herself was never diminished. So during her final decades in London, where she had to rely upon maybe picking around scraps of fabric and pinning things on herself, she was very Vivienne Westwood and very punk and very inadvertently, she's been called in the press, in connection with our work, you know, the grandmother of God.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:So so, Valerie, I'd I'd like to, perhaps as we wrap up, for you to bring us up to date in how the Marchesa has been rediscovered by new generations, how she's become a figurehead in the goth community. And one of the most satisfying results of our work on, the Marchesa is that a year does not go by when 18, 19, 20 year old students, fashion students from around the world are always reaching out to us, breathlessly proclaiming their discovery of the Marchesa and how she is their icon. That's remarkable.

Valerie Steele:Well, when I worked on my show, Gothic Dark Glamour, you know, I had an endless dream of black clad young people who were also aware of the history of literature and art and film and who really identified with all of these historical figures. It was really fascinating. I mean, you see how the history of the symbolist, you know, idea of the femme fatale or even going back further to the romantic imagery of, you know, the Medusa or, you know, someone sitting there like a dangerous female. And this led up to be popularized with Theda Bara and vamps and then vampires and the sexiness of vampires. It was strange because that show which so appealed to young people and especially, you know, sort of English people and American young people.

Valerie Steele:But I remember I had a group of Italian fashion executives that I was showing through Gothic, And they were sort of horrified. Like, what is this? Some kind of Halloween show? And then I said, but look. This is Galliano's.

Valerie Steele:He's inspired by the Marchesa Casati. And they went, oh, La Decadenza. And finally, they had something, you know, that they could identify with. But in in these ways, you see young people in the golf community looking back and pulling her out as an icon. I think that it's that kind of what Walter Benjamin talked about, the tiger's leap into the past where if there's something that we desire now in fashion, we can find it in the past and bring it back and bring it back to life.

Valerie Steele:And so she continues to be an iconic figure both for fashion designers and for young people, subcultural people.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:Wonderful. Well, thank you so much. I really feel that we've gained a few valuable insights with all of your amazing contributions to this. I wanna thank each of you for your sharing your thoughts and ideas, which have all expanded the dark and amazing and beautiful universe of the Marchesa Casati. And I will just end with the little tagline that Scott and I devised twenty five years ago with the very first publication of the first edition of the book, and the University of Minnesota Press, I might add, released a paperback version that was revised in 02/2004.

Michael Orlando Yaccarino:And then more recently, they showed such support of the ongoing interest in infinite variety that they did something rather remarkable, which they rereleased the book, which they had only, up until that point, printed in paperback as a new hardcover. And they agreed to all of our revisions. So, that 02/2017 University of Minnesota Press is the most up to date version of the book with so many little treats and treasures in it in the English language. But I wanted to just end with a little tagline that we would, share with anyone interested in the Marchesa, in reading any of the biographical works that we have done, and each of the participants' wonderful work is prepare to be astonished.