How the ordinary postwar home constructed race in America

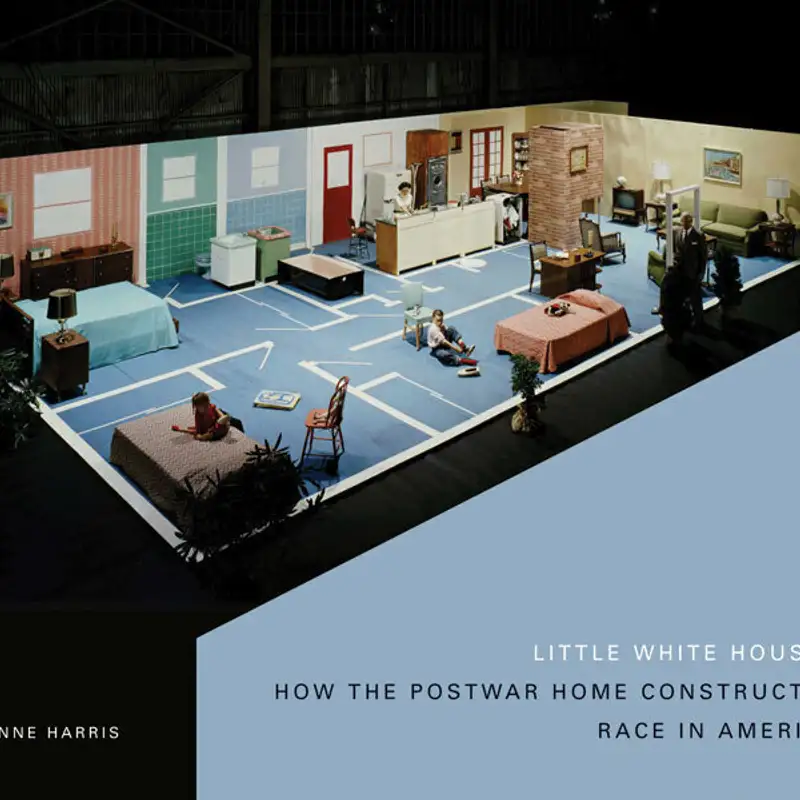

I think we have to understand housing at every level we can possibly understand it. And if we're gonna really understand what has undergirded the ability for this country to very purposefully not see the ways housing discrimination has been enacted over decades and decades and decades of time. Hi. I'm Diane Harris. I'm the author of, University of Minnesota Press book, Little White Houses, How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America that was first published in 2013.

Dianne Harris:And has just, I'm very pleased to say, gone into a second printing that's now out that was just came out this year. And on that occasion, I'm here to talk about the book again, with my colleague, the brilliant Mabel Wilson. Just to introduce myself briefly, I'm an architectural and urban historian. I am, newly the dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle, and I'm thrilled to be here with Mabel.

Mabel O. Wilson:Yeah. Thank you, Diane. It's a pleasure to be back and in conversation, about the second printing of your book. And just one to say congratulations. I am a designer, a cultural historian, curator.

Mabel O. Wilson:I teach at Columbia University, both in architecture and also in African American and African diaspora studies. And I'm really excited to, again, be in conversation with you about little white houses and how the post war home constructed race in America. And I sort of wanna begin there maybe with a question for you because we often think the home, the suburb is constructed by race, but we also don't think about how the home actually constructs race in America. So can we start with a little bit about the book's origins?

Dianne Harris:Absolutely. And it's a pleasure and a delight to be in conversation with you about the book as well. You know, to have been able to have the opportunity to talk with you, my friend, as a as a scholar and a thought partner and as a, as a supporter for the work over these many years has been, just incredible. And and your work has influenced my own in in so many ways. So thank you again for doing this today.

Dianne Harris:So I started working on the project many years ago. It started as early as 1996, actually, just shortly after I had finished my dissertation, which was on an entirely different topic on the eighteenth century. It it focused on, eighteenth century Northern Italian villas. But it was also about questions of belonging and exclusion and identity formation in and through the built environment. And I just had an opportunity when I started my my very first academic tenure track job at the University of Illinois in 1996 through, one of my dissertation advisers, to have the opportunity to start looking instead for briefly for a symposium on questions about what was happening in the ordinary postwar suburb, between 1945 and 1960.

Dianne Harris:And from that project, I started to look differently at all kinds of questions. And I what I really wanted to understand from that point forward as soon as I started working on this was I really wanted to understand the millions of houses that belonged to a majority of middle class Americans after the end of the second World War. They were the houses that frankly had surrounded me for most of my life since I've been a child and that I'd lived in and that I encountered everywhere in the built environment outside of large urban centers. They were everywhere around me when I moved to, Urbana, Illinois. I saw them every time I drove to the grocery store, every time I took my daughter to to school, every time I went to work.

Dianne Harris:Yet, I could find very little in-depth scholarship about them. I noticed that suburban histories, and there were some really excellent ones, out there in 1996, focused primarily on the planning of suburbs themselves, but not on the houses. And once I started digging in during the late nineteen nineties and the very early February, I found glancing references in the published scholarship to the segregated nature of these houses and neighborhoods. But at that time and and you'll remember this, Mabel. There was really nothing in the architectural history literature about this aspect, about race and racism and houses.

Dianne Harris:At least, you know, nothing that was more than a couple of paragraphs that would say something like, you know, and, of course, these houses were restricted largely to whites. And I kept reading these paragraphs and thinking, really? That's that's the end of the story? That's all you're gonna tell me? Planning history is told a bit more about redlining practices and so on, but nothing that dug more deeply, into the houses themselves and not much elsewhere, either when it came to really understanding that topic.

Dianne Harris:So I've long been interested in questions of exclusion and belonging in the built environment. And as I said earlier, my first book and my dissertation focused on those issues in a totally different context. But these became compelling questions for me, and they remain so during my career. The autobiographical piece of the book, which I'll talk a little bit of, more about later, generated a really powerful resonance for me between what I knew about my family's history and these issues of discrimination and exclusion and unfair housing policies and practices that kept large numbers of folks out of the housing market then just as they do now. So it started as a fairly straightforward architectural history driven by what were at first a fairly conventional set of questions about ordinary post war houses.

Dianne Harris:You know? Why did they look that way? Why were they the sizes they were? Why did they grow, by several hundred square feet over the period that I was interested in studying? Where did people store all their stuff in a time when credit was more readily available and people had more income than they'd had before, but these houses didn't have basements or attics because they were building slab on grade for the first time in many parts of The US and not always having basements and often not having basements.

Dianne Harris:You know, these are very traditional architectural history questions became one that focused on questions of race and post war houses. And the more I researched the project, the more I realized that a big part of the story was about white supremacy and the ways ordinary post war houses became vehicles for various modes to assert white identities and the unearned privileges and dominance that obtained to them. It became clear to me that those were the compelling questions about these ubiquitous houses and that the real story to be told, or at least the one that I needed to tell, was about trying to understand the links between houses and the ways race and identity are intertwined and formulated. I wanna say too that there there's always been a driving sense for me as a scholar of trying to understand those questions, but I also found myself at the University of Illinois amid a group of scholars and in a very rich intellectual environment where I was able to learn more, than I would have, I think, in many other places. It was a place where there was, an incredible vibrancy and fertile ground for folks who wanted to do interdisciplinary scholarship, opportunities to connect with brilliant historians, theorists, folks in ethnic studies, race studies through the humanities center, through the center for advanced study, and coffee shops.

Dianne Harris:It's a re an unusual place that way. And I think being there too and being around a group of scholars who are working on similar issues helped advance my own work in this area and and probably substantially helped shift the the direction of the questions I was asking. So all of those forces and factors came to bear on the shape of the book and how it ended up being the book that it is that really focused on this looking at these questions about race, belonging, exclusion, identity formation, racism, segregation, white supremacy, but all through the granular sort of micro level of the house, its possessions, its arrangement display, rhetoric, advertising, and so on.

Mabel O. Wilson:And and with that in mind, thinking about, you know, how you start to craft, a kind of language, right, for understanding race in the built environment. That's why I found the book so revelatory, and useful in my own teaching, teaching graduate students. But also, you know, I've I've used the the book for courses that, you know, that aren't specifically for, let's say, architectural historians or designers. Outside the field, there's a kind of rigor both in the method, which I I wanna follow-up with you about in part, but also very just very clear descriptions about, you know, like, what race is, what whiteness is, and why it's important to think about it in in regards to the built environment. So can you explain how you define whiteness and why it's important to understand this in relationship to architecture, especially since it hadn't been a question previously?

Dianne Harris:Absolutely. And, you know, it's a good segue from what I was just saying about being at Illinois because I've really been profoundly influenced by a generation of scholars whose work really arose, in the nineteen eighties and nineteen nineties, kinda became better known and established. And there are scholars who really forged the field of critical studies of whiteness. David Roediger, who was a colleague of mine at Illinois, whose work has been profoundly influential for me and who was incredibly generous in taking time to to to teach me and to share sources and ideas in the, beginning stages of this project. But then a range of scholars who are examining the fluidity of white identity and over long periods of time and what that's meant for Jews, Italians, the Irish, Mexicans, and Asians.

Dianne Harris:You know, Matthew Frye Jacobson's work was as important to me as Karen Brodkins was. And then we began to see some scholars who study the visual world focusing on whiteness as a theoretical category as well. Scholars like Martin Berger, for example, whose work is just really superb thinking about whiteness and visual culture. So I've always been having said that. So that's sort of the the some of the scholars who influenced this work and helped me think about how I'm defining whiteness.

Dianne Harris:But I've always been very aware of the critiques of that work. So I wanna say that too before I go back to thinking about the definition. And especially the charges that critical studies of whiteness has just been another way of putting whites at the center of everything. Legitimate critique. Right?

Dianne Harris:Something to really be aware of. But I believed then, as I do now, that we cannot dismantle white supremacy if we don't understand very deeply how it operates and the structures through which it defines and asserts itself. So for me, housing is one of the most pervasive and pernicious of those structures because it can seem so benign. And the ways whiteness asserts itself through architecture and material culture related to houses is so subtle yet powerful and persistence that for me it demands that we examine it and we examine whiteness through it. So I define whiteness as a racial category that had a fairly significant degree of fluidity throughout the twentieth century and remains in flux today, but that has been static in the ways it consistently aligns with modes of dominance and supremacy that are linked to the most traumatic, devastating, and harmful aspects of this nation's past and present.

Dianne Harris:There are scholars today who would define the construct that is whiteness as a pathology. And because of its ties to the trauma and harm I just mentioned, and if we were to be honest about the past at all, we have to see it that way. It's important to understand it in relation to architecture because the built environment is one of the most powerful structures through which white supremacy circulates and persists. But one of the things I'm fairly insistent on in the book and that I hope readers take away from the book is the fluidity of whiteness. The ways in which it has, on the one hand, morphed and changed and moved over time to accommodate different historical forces, and the subtleties of of history and those forces while at the same time remaining static, as I said, in its dominance and in its force toward domination.

Dianne Harris:Right? That that's always kind of at the, forefront of what whiteness seeks to be. I try to help students understand, you know, as as all of us who work with students and try and try to help them have a more nuanced and rich and full and accurate sense of race and racism. That race is a category, that it that has shifted over time, a set of categories, that it's a construct, that skin color is not always nor, is it consistently what race has been about, but that skin color is the manifestation of the structural forces that come to play through those constructs that make up racism and race and whiteness. I actually spend a good deal of time in the beginning parts of the book walking readers through that because I just couldn't be sure that any of, the readers who I imagined to the audience would have been familiar when I wrote the book with that work.

Dianne Harris:One of the things that's really interesting to me right now, and we can talk about this a little bit more later too. When I was writing that book and even up to the point where it was published, the words white privilege were not really in particularly wide circulation. I think it's fair to say they now are, and that's a remarkable shift in in our culture that deserves some attention, I think, and is getting some attention. So, the book, I don't think, has much to do with that at all, but, but it's interesting to to think about that change that's happened in that in the intervening eight years.

Mabel O. Wilson:Yeah. No. I I think that's absolutely right. I mean, I think that's one of the innovative dimensions both of your, you know, of the the book's content, but also of the the method by which you under undertake it and to really scrutinize whiteness. Because often in architectural scholarship, people would focus on, for example, the failure of modernist housing, writing it, right, race as blackness.

Mabel O. Wilson:Right? That, you know, there's some sort of clearly so so, you know, social failure, you know, that results in the inability of the housing to sort of accommodate a certain kind of of social life, in fact. And so race always often gets, you know, associated with blackness and whiteness sort of remains transcendent and and transparent. You know? And those let's say the the histories can go to the archives of a Yamasaki.

Mabel O. Wilson:It can go to the archives of a Chicago Housing Authority. Right? And and write those narratives. And I think, you go to other sources. And so can you you maybe share a bit about the kind of methodology of what you you look at and and why it's important?

Mabel O. Wilson:And I think why it's important in part is because I think one of the things that's clear, you know, is that institutions are significant in how they shape racial discourse. Right? And the ways in which then individuals live that. And and I think you find these archives with really remarkable content. So so yeah.

Mabel O. Wilson:Can you can you share more about the the method of writing?

Dianne Harris:Sure. And, you know, as a lead into that, it's interesting to think about when you mentioned, you know, the example of public housing and high you know, high rise public housing, for example, and the ways that that's been considered in terms of race. One of the things I would say, you know, when I started out earlier saying that there wasn't much in architectural history that had to do with race and architecture when when I was writing this book, I would nuance that by saying that when architectural historians have written about race before Little White Houses and and before your work, and I wanna really importantly point to your work, Mabel, as a real inspiration from my own, with, you know, Negro building coming out very shortly on on the heels of of the White houses and and having wide influence on so many. And we'll talk about that in a minute too. But when architectural historians were writing about race, they were doing it in spaces that they understood to be overtly racialized.

Dianne Harris:So, you know, a so called ghetto, a barrio, a reservation, a Chinatown. And in those instances, there were particular methods for doing that. You know, if it was high rise housing, you could probably go to an architectural archive if you're an architectural historian and find plans and drawings and documents pertaining to that. Harder to do, but, in the context of, say, a Chinatown or, an American Indian reservation, but scholars of the so called vernacular, world have been doing that for some time and and sort of finding a wider range of of collections and and evidence on which to base that work and doing superb work in that in that way. But what I was trying to do was to show through this book that all of the built environment is about race, whether or not we understand it to be that way because the spaces that have been considered to be not raced are white spaces and that they are therefore racialized and are very much about race and exclusion and identity.

Dianne Harris:So I was really trying to turn that piece of architectural history on its head. I'm gonna go back a little bit when I think about the method, and especially I wanna talk a little bit also about the autobiographical aspect of the work, which is a little bit of a piece of the method. So I grew up hearing a lot of stories from my my maternal grandparents, who immigrated who were Jewish, who immigrated from Germany to The United States about houses. And I heard about them in at least two ways. One was that my grandfather was an electrical engineer who specialized in high fidelity sound systems and had his own retail store, on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles in the '19, forties and fifties and into the sixties.

Dianne Harris:It was called Weingarten Electronics, and he did high end custom installations of stereo systems, into architect designed homes. And he was fascinated with architecture from the time he was a young man in Germany and was fascinated by what he saw and heard about and learned about happening in the Bauhaus. He was a passionate fan of our of of mid century modernism. And, so he would tell us stories whenever we visited about the architects he worked with. And so my my older sister, who is an architect, and I especially, grew up hearing those stories and being very, very influenced by them.

Dianne Harris:And and he he really enjoyed working with with the architect. He worked with Richard Neutra, with Quincy Jones, with John Lautner in Los Angeles and had wonderful stories to tell about them. So there were those stories just about architecture that were interesting in modernism. But there were also the less frequently told stories because I think my grandparents were in some ways, sort of typical in their their optimism about what The United States promised them as immigrants. And so they tended to focus on all the positive things in their lives.

Dianne Harris:My grandfather and grandmother would sometimes talk about their search for housing when they arrived in California. And I understood over years because they didn't talk very much about the kinds of exclusionary practices that kept them from readily finding houses in that time. I only found out later as an adult about some of the challenges they faced in finding housing. And, so, of course, in the book, I spend a good deal of time focusing on their their ordinary post warehouse that they ended up purchasing toward the end of the nineteen fifties, in the San Fernando Valley in an area that was not, exclusive, for for Jews. So I wanted to tell their story not because it was unusual, but because it was so common at that time.

Dianne Harris:And I knew telling it would help me set set the stage for the detailed granular study of residential segregation that I hope to tell. But I also imagine their story would resonate with many other Jews who might have similar immigration stories in their families and with others whose families have immigrated and experienced similar struggle struggles with with unfair housing. And it seemed to me that telling their story did at least two things. First, it helped me provide some nuance to questions about race and space. And and this is something that seemed very, very important to me as as I was writing the book.

Dianne Harris:In The US context and and as I wrote in the book, I felt it was important to shape a narrative that would help readers understand the race beyond any single binary. And that seemed especially important since I imagined my primary audience to be architectural historians who might not have had much familiarity as I said earlier at that time with theories about race and whiteness. So my intention by including the story of my Jewish immigrant grandparents in their home was to remind readers of the of the many folks who are excluded from the housing market by racial racial covenants, by redlining practices, by real estate steering, and so on whose skin was black or brown, but also those who were excluded because they were Jewish or Muslim or even in earlier days Italian or Irish, including the story of my Jewish grandparents and details of the home they were eventually able to purchase and that they cherished. They cherished this little home as a signal of their own arrival as real Americans. And and it really for them was a signal of their belonging in this country.

Dianne Harris:And they faced a lot of exclusion even after they got here and got into that house. But it helped me to tell that complex narrative of race and ethnicity defined in ways that have shifted over time, but that have also remained unfortunately static. Second, I wanted to experiment with academic and scholarly writing. I wanted the book to reach architectural historians, but I also hoped it might attract at least a small audience beyond the academy. I've always kind of wanted to do that.

Dianne Harris:I've aspired to that. I'm not sure I know exactly how to do that. And I think a lot of us as scholars struggle with that, but I'm interested in that. And I wanted it to perhaps help interested readers understand more about the ways housing and segregation happens, about the ways the lack of access to real property shapes life chances and diminishes them for folks who can't access it, and to better understand some nuances of race and racism in The United States during that period between 1945 and 1960. And I wanted to do that also because everybody lives somewhere.

Dianne Harris:You know, a residential experience is so common. And so it seemed to me that using a book like this to help more people understand how racism operates in and through the built environment was a real opportunity. So using autobiography was partly an effort to experiment with the those conventions of academic writing, which we know are pretty rigid. And it was partly an effort to engage a wider audience. So if nothing else, I do hear consistently from students, about how much they appreciate that aspect of the book.

Dianne Harris:I think everybody likes to read a story. I do. And I also love to write. So that part was quite frankly just a really enjoyable aspect of the project for me and one that held a lot of personal meeting meaning, and and just joy. I don't think it's an appropriate approach for every or even for most projects.

Dianne Harris:I don't think we always need to insert ourselves into the narrative of the scholarship. But I do think it it it does important work in little white houses for the reasons that I have mentioned. Methodologically, there were some interesting challenges for this book because architects mostly haven't written about race explicitly. You know, it's every now and then and, you know, a project I've worked on recently where you'll find an architect who scrawled something really racist in the margins of a document or more than one document. But that's not very common, in my experience.

Dianne Harris:So understanding the ways whiteness whiteness and its dominance was shaped in the housing market, as an absolutely de facto assumption meant looking at different kinds of sources and developing an ability to decode more commonly used sources. It really meant often doing the opposite of what we're trained to do. As architectural historians or art historians, we're trained to look to look carefully at what we can see. I think those of us who work on race develop an ability to look for what has been consciously and sometimes not consciously erased, suppressed, buried, but that is always there running through it as a kind of resonant current if you look for it. I had to learn to decipher what I came to think of and to write about as codes for whiteness that were both textual and visual or material to understand the underlining meanings of ubiquitously and consistently deployed rhetoric about cleanliness, spaciousness, privacy, order, mobility, words like that that came up over and over again in the literature on these houses.

Dianne Harris:And then to just really analyze them and to look at how those those terms played out in terms of who the presumed audience was for these houses. If you look carefully at these houses, and I've talked I don't really talk about this in the book so much, but it was one of the things that prompted me to think about kind of codes and spatial dynamics of houses and how the houses tell us who they're for. I kept thinking about, again, my grandparents' house and how their postwar home didn't have a place for them to keep their extra set of kosher dishes. They didn't keep kosher, but we had family members who did, and there was no place in the house to do that. My grandmother had to keep them out in the garage.

Dianne Harris:Or her built in countertop range, it was a stovetop, and the the oven was separate, which is very common in post war houses. And her range had four burners, on two on each side of a griddle and, you know, it was called a pancake griddle. Well, my grandmother didn't make pancakes. She made matzo brei. And, you know, so every time she used her pancake pancake griddle, though, as a German Jewish immigrant who probably hadn't made pancakes much before, her house reminded her that she wasn't quite its intended occupant.

Dianne Harris:And I think about that a lot. How do our house houses tell us, you know, who they were intended for when they were designed and built? And it's usually not for anybody who wasn't a white Christian American. So all of those things were were interesting to try to think about those codes and the different ways we can look at those houses. Finally, I'd say a a key challenge of the book was that I wanted it to have a national scope, and there was no single archive for the kinds of houses I was writing about.

Dianne Harris:And in fact, they're you know, for most of the really ordinary houses I was looking at, they were they were builder houses. They were often made by builders who didn't have any kind of affiliation with any kind of a big build. They weren't Kaufman and Broad, for example. Right? As we would think of it now, they were just, you know, small time builders.

Dianne Harris:So the questions I was asking can't actually be answered in most architectural archives anyway. So that may meant thinking differently about how I might find answers to the questions I found most compelling. And in the end, I'll have to say I did find some helpful evidence in a couple of architects' archives. The archives of the architect a Quincy Jones was really useful, but mostly for the clip files, not so much for the houses themselves, where I found really odd and interesting things. There's something called the Small Homes Council archive at the University of Illinois that, with that was a a a research council, a research center at the School of Architecture there where they got a lot of did a lot of grant funded work on building ordinary small houses.

Dianne Harris:So it was useful. And then for the chapter on television, the NBC archive that's located at the University of, Wisconsin in Madison, was enormously helpful. But I mostly had to hunt in a lot of strange places to find answers to questions. And so, you know, I used government documents. I used novels, films, trading stamp collection catalogs, redemption catalogs, popular and shelter magazines, lots of those.

Dianne Harris:They're their own kind of archive for this work. Photographers' archives, advertising records, All these became essential parts of the story I needed to to tell. So an interesting an interesting kind of treasure hunt in many ways.

Mabel O. Wilson:Yeah. I mean, I think that's what's so rich that each chapter has its own sort of archival bend and that you can sort of sense the degree to which. And and I think this is important that media, right, that these magazines that, you know, that they were circulating this. But these these magazines were also backed up by institutions, that there were, standardization in, you know, organizations that were promoting certain things, that there were associations of architects who were engaged. It was the Museum of Modern Art was also engaged in building, you know, American taste in that post war period.

Mabel O. Wilson:And so while and and and that's the thing that I appreciate is that you oh, you think these are just throwaway things. Right? It's this month and, you know, house beautiful. But, actually, you know, you they they they were institutional constructs that are that are constructing a national narrative, particularly in that post war period as immigrants are coming into the country. We're having civil rights struggles that, you know, that that these are also sites in which America is being imagined and also contested.

Mabel O. Wilson:And that's sort of what I appreciate and how the chapters really do unfold.

Dianne Harris:Oh, thanks. I mean, I that's a it's an interesting point. And I think, you know, one of the things that was so interesting to me about thinking about shelter and popular magazines as their own archive is that, as you said, it's easy to take them at face value and really important not to. And to think about especially in that period when magazines like House Beautiful, which today is not, you know, it's not a particularly influential magazine at all. But in the nineteen fifties and into the nineteen sixties, it was a very influential magazine when it was under the leadership of a particular editor, Elizabeth Gordon.

Dianne Harris:And there was a at that time, I think much more today. I mean, much more to than today because it almost doesn't exist now. A kind of interesting set of interactions between the profession of architecture and a kind of, you know, even well known sort of, you know, what we call might call high style architects and these popular shelter magazines. You know, they were in conversation with each other because the architects understood two things, I think. One was that merchant builders cared what was in those popular magazines and shelter magazines because readers wanted what was in them.

Dianne Harris:And so there was a kind of interesting constant circulation and flow of information and feedback, a kind of a feedback loop that went from the profession to the editors of those magazines to the readers and back again and and then circulating in and among the merchant builders and the building trades who are, you know, creating a lot of these houses. And so they became much more influential than they are today. And even, you know, one of the sources that I relied on a lot was, Popular Mechanics, which had a huge influence and was, you know and may maybe does still, but to a different kind of audience and around different kinds of issues than it did then. So, yeah, very interesting archive of its own.

Mabel O. Wilson:Yeah. And I and I think in particular, there was a show recently that sadly just closed at the Jewish Museum called the Modern Look, you know, that looked at the impact of European emigres, artists who are coming into The United States. And one of the places they found work was in the New York publishing industry and fashion magazines and and and shelter magazines. And it was just really remarkable to see these avant garde techniques of photographing objects, places, and peoples being deployed in these men. So aesthetically, they were really sharp and quite interesting, You know, but we often don't see that.

Mabel O. Wilson:We see the fine art production, but we actually don't see how they're engaging, in everyday life. And that would include people like also Gordon people like Gordon Parks were also a part of that. And so there were these dialogues amongst all of these these creatives that just aren't necessarily taking into account in, let's say, the canons of art history or architectural history or design history for that matter.

Dianne Harris:Absolutely. And then, you know, one of the things that I I talk about a little bit in the book too is, you know, the extent to which the presumed audience, of readers for those was a white audience and that the ways that that gets reinforced representationally throughout the the genre of these sheltered popular magazines. And thinking about them compared to what existed for, say, a a black audience, which would have been Ebony more than Jet. Jet wasn't really the venue for, you know, Ebony was the large format kind of glossier, more more heavily illustrated, journal. And to be sure, there are features on housing in Ebony over the same period of time, but they're quite different.

Dianne Harris:And, because the, masthead in Ebony, you know, the the kind of statement when you opened the the magazine was that it was to portray the brighter side of Negro life, housing wasn't gonna be part of that. You know? Housing was not actually at that moment readily available new housing to to blacks in America. And so it would been would have been hard to feature that in in the at the kind of scale and scope that it was featured in the the shelter magazines intended for white audiences. What you do find in Ebony, and others have written about this, people like Andy Weese, for example, in his his book about African American suburbs, is, you know, more houses for prominent black figures in American life.

Dianne Harris:You know, a doctor, an astronaut, someone who has attained a level of fame and wealth so that they could build their own home in a in a suburb, where they knew that they would be welcomed and safe, for example. Just an interesting point of comparison when you think about those two sources for the project or multiple sources for the project.

Mabel O. Wilson:Yeah. I mean, I think, you know, thinking about audiences, I think, sort of critical. And maybe to shift a little bit to think about and and and discuss, like, what was the response to the book initially, and its impact on the field? Because not that many books get a second printing. Right?

Mabel O. Wilson:In this way, also, you know, with with years past. So there was something about, I think, the book that you can say was was ahead of its time.

Dianne Harris:Yeah. Thank you. I mean, I'm happy to say I think now it's been really favorable. You know, reviews of the book were overwhelmingly favorable. I can think of one where somebody was kinda not happy with it.

Dianne Harris:But, for the most part, really favorable, and I think it's been especially impactful for students and for a younger generation of scholars from whom I hear pretty frequently. I think younger scholars were really ready for this work, and I really think they're the ones who are gonna carry its questions forward in important ways. You know, I know from my own private Google citation scholars page that it's very widely cited and, you know, it seems to kind of pick up as time goes on actually as it gets kind of more well known by scholars. It's been great to see the ways the book has been taken up by scholars from a a wide range of disciplines, because I see the book cited, for example, by ethnic studies scholars, sociologists, geographers, and by scholars in in Jewish studies and communication, material culture studies, media studies, gender and women's studies, and, of course, you know, historians as well as those who study architecture landscapes. And that was really a goal.

Dianne Harris:I really wanted it to be a book that would help scholars in other fields see the importance of the built environment for these issues. Because, you know, one of the things, Mabel, you and I have talked a lot about is the extent to which for some reason, the built environment is seen as something that is just not a significant cultural force in the way, for example, a piece of writing on a document in an archive can be. And I find that so strange in a certain way because the built environment is everywhere in our lives. It shapes our experiences every day in, you know, a thousand myriad ways that we are mostly not conscious of, but that is profoundly important for the ways we conduct ourselves for what we have access to, for what we don't have access to. I just that that piece of it to me just felt incredibly important and ever more so now, you know, in that kind of national moment of reckoning around race that we're in.

Dianne Harris:So seeing the work being taken up by such a wide range of audiences has been enormously gratifying. But it's also been exciting to know that some nonacademic reading groups have selected the book and have found it a good source or starting point for talking about whiteness since it again, it connects to something that everyone has experienced, which is residential life. You know? That's just something that everybody knows. So it's a it's an entree.

Dianne Harris:If you if you have a group of people who wanna explore white privilege, the way white supremacy works, starting with something that we all know every day, the place we live, where it's whether it's a house or an apartment. It's a great way to start thinking about and talking about these really complicated and difficult issues.

Mabel O. Wilson:Yeah. Can you can you talk about also specifically on architecture? Like, what what was it its impact, do you think, on how architects were considering this question of racial thinking?

Dianne Harris:Oh, it's so funny that I left that out.

Mabel O. Wilson:Yeah. Because I also think that that is the brilliance of the book because it's it's interdisciplinarity, but it also teaches, you know, particularly historians of architecture, as you said, to to look at what, you know, that might be overlooked. That that isn't necessarily seen or even considered relevant.

Dianne Harris:Yeah. So I think in architectural history I mean, it's really hard for me to say. I hope that it's had an impact in architectural history. I think it has. I know that it's included on a lot of course syllabi, which is great.

Dianne Harris:To me, that's the impact I'd rather have any day than knowing that it's cited in a bunch of other books. Having students read it means everything to me, because I think that's really impact. I am hesitant to say that it's Little White Houses that has done this. I think it's Little White Houses and a constellation of publications that came out around the same time or just afterwards. Your book, Negro Building.

Dianne Harris:More recently, Charles Davis's book, that I'll talk about in a minute, you know, the race and modern architecture book that just came out. And certainly, I wanna, also say that the work of the incredibly important and influential work of someone like Del Upton, who was writing about race and landscape, people like John Michael Vlach, who helped us understand the plantation in new ways. I mean, there have been scholars working on Rebecca Ginsberg, whose work on, apartheid and and houses in Johannesburg. These are all have all been incredibly influential. Texts and I would even go back to a book that's been so influential for me, James Borchardt's, alley life in Washington DC, which was written a long time ago and talk about a book ahead of its time.

Dianne Harris:I mean, that was a really brilliant book. So certainly people have been writing about race and architecture for some time, but it it would be hard to say that it was any kind of a real current, until very, very recently. And I remember, in fact, the first time, I think it was, in the early two thousands, there was a special issue of the journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, and I was asked to write something about social histories of architecture. And I wrote something about critical studies of whiteness and the built environment, and I was very conscious as I did that that it would be the first time that those words were published in the Journalist Society of Architectural Historians ever, and that nobody had been thinking really about whiteness studies and the built environment, or writing about it until then. So, you know, I don't want it to claim too much for the book, and I I really think that it's a constellation of efforts and of scholarship that have really kind of made a difference in the last five to seven years.

Dianne Harris:But I'm thrilled to see that, you know, for example, at the annual meetings of the Society of Architectural Historians, there are multiple sessions now having to do with race and architecture. There are roundtable sessions. There are events that happen outside of the annual meeting that the Society of the vernacular architecture forum has been supporting this work for a very long time. So I I think what the book did in terms of changing architectural history is, that it contributed at a moment when more was about to happen, when the field was starting to be ready to have those conversations in ways that it not only hadn't been before but was resistant to. That resistance is still there.

Dianne Harris:There it is very, very much still there, and it runs it runs deep. But I have enormous hope in this new generation of scholars that are coming up, who are really interested in these issues and who understand them to be central to our understanding of the built environment. In terms of the profession of architecture, I know less about how the book if the book is known among architects. I just don't know. I'm not in practice.

Dianne Harris:I'm not teaching design studio. I'm not I haven't been embedded in an architecture or design school for quite a while. My guess is not so much. And that's where I would love to have it see it have an impact because I think it's with the people who produce and plan and design the built environment that change needs to happen, probably more than anywhere else. So I'm not sure how that will happen, but but, I think it will happen when design schools decide that they need to go through the kind of culture shifts that we think, you know, they are just now starting to wake up to.

Mabel O. Wilson:But you have, recently, and this was a conversation we had at Dunbar Oaks that you showed. I mean, this also brings in, you know, that these weren't just minor builders and corporations, companies making these suburbs, but figures like Frank Lloyd Wright were actively engaged in, you know, certainly with Broadacre City, but also the work that you you study and sort of thinking about these things. So it's it's it isn't far a field. This is actually a central question to modernism in that moment. And and and could you talk a little bit about, you know, which which kind of speaks to work that you're you're engaged in now, actually?

Dianne Harris:Yeah. So, you know, thinking about what what I might write a little bit differently, given current debates, you know, what what I might think about differently. And you're absolutely right. I mean, I think that the it's interesting because I didn't know, you know, obviously, about the right work, the Franklin Wright rights work, that I just have been working on, with Broadacre City when I wrote this book. I did know that merchant builders like the Levitts were looking at Frank Lloyd Wright's work and in funny and interesting ways trying to incorporate some of his design, stuff into their mass produced housing, which is kind of interesting.

Dianne Harris:So, you know, but what I'm trying to was just trying to signal is that I not so much that I don't think there's much to be learned by looking at what arc you know, sort of well known architects have done, and thinking about these issues, but just that I don't know quite as much about where and how practice people in professional practice are thinking about these matters yet. I hope they will. So thinking about what I might do differently with the book, as I mentioned when I started working on the book in the late nineteen nineties, there were less than probably a handful of architectural historians, you know, whose work focused explicitly on race, as I said. And none that I could really point to who had considered scholarship, on whiteness like that developed by historians like David Roediger. But I think it's fair to say that the audience I imagined is the primary one for the book would not have been much aware of the key scholarship on race or critical race theory, for example.

Dianne Harris:So I spent time sketching out those histories and theories for the for those readers. I'm not sure how much of that has yet changed in terms of awareness of those theories and that literature among, you know, many, many scholars of the built environment. But what has changed is a dramatic shift over the last couple of years in the field of architectural history in terms of a more widespread realization of the gaps in the literature in our field. They're really more like chasms than gaps. And I'm I'm incredibly excited to see a new generation of scholars stepping in and up to address new questions that center race in their work.

Dianne Harris:Books like your own, the edited collection you worked on with Irene Chang and and Charles Davis, Race and Modern Architecture, and Charles' book, Building Character. I think all of these are making a real difference in just the last eighteen months. They're selling briskly. They're really, opening the eyes of designers and historians, I think, to new ways of thinking. But also, you know, the recent reconstructions exhibit that you curated taught me a lot.

Dianne Harris:There's a good deal more I think to be written, that I learned, by thinking about the reconstructions exhibit about where black folks were living their hopes and dreams, about black joy and about Afrofuturism. My book focused pretty much on exclusion and on the ways whiteness worked then and now as a dominant force that seeks supremacy, domination, and exclusion. And I felt then as I do now that explicating that in detail and in the most granular level was important if that process was to be fully understood so that it could be dismantled. But if I were writing the book today, I would have included at least a bit more about the agency of black people and other people of color to forge communities, vibrant neighborhoods, freedom colonies, and more. That's that's a piece of the book that's really missing.

Dianne Harris:And at the same time, I would perhaps spend more time if I were writing the book today trying to better elucidate the ongoing impacts that have led us to this post George Floyd moment. That might be too much for one book to try to do. There's a lot to do in that book as there is in any book. But I do think we're in a a really different moment than we were in when the book came out in 2013, just, you know, seven, eight years ago. You know, we could ask how, for example, we might think about housing when we consider, as I believe we must do, questions about reparations.

Dianne Harris:That's not something that I included, but it could be a really interesting interesting new prologue for the book if it were to be rewritten.

Mabel O. Wilson:Yeah. I mean, as you know, I I grew up in a little White House in, suburban well, not quite suburban New Jersey, but, and it's a it's an interesting story actually about it. You know, there was a builder who built the neighborhood, you know, he was actually a Jewish builder. And so they are those stories that I think have have yet to be told. But also, you know, like if someone, yeah, somebody your, your book is on a book club's list, for example, and somebody's thinking about reading like, okay, I'm gonna pick this up.

Mabel O. Wilson:You say, and you know presciently in the, the epilogue that it's a mistake to presume that that discrimination doesn't exist in the housing market and that the market is actually fair, an open market. And so how, you know, how might this be a kind of lens to understand, like, what's going on to help people connect the dots because often more often than not, they see this as a current circumstance and maybe don't see the larger historical frame as to why things even today are are the way at which which they're they're constructed.

Dianne Harris:Absolutely. I mean, I think that the line in the books that the fight for fair housing is not over, and it sure as heck isn't over. You know, there's an enormous amount of work to do on fair housing, and we heard about it in the last presidential election from some candidates a candidate, not as much as I would have liked to have heard us hear from others. It's astonishing to me the extent to which fair housing is not a current topic of conversation considering the kind of bonkers housing market, that we're experiencing right now, the extent of homelessness and housing precarity in that we saw before the pandemic, let alone now in this ongoing pandemic situation. And the deep understanding we have, there's no no way we can say that we don't know the extent to which address is linked to productive life chances.

Dianne Harris:We know exactly the connections between where one lives and what one's opportunities are. To just have a dignified life, of of opportunity, the kind of life and opportunity that we believe everyone should have in an equitable, fair, just society. I would love to see, Little White Houses in this next part of its life become a jumping off point for the connection to an entire syllabus of of fair housing as part of a, you know, courses on just futures, equitable futures. Because to me, housing and understanding its deep history at every level, it's great to know about redlining. It's great to know about what happened after redlining.

Dianne Harris:There's some fast fantastic literature on that that's come out in the last few years. I mean, I can't say enough about the work that Keanda Yamada Taylor has put out that I mean, that book is spectacular. Her Race for Profit book is spectacular and so important. Richard Rothstein's book on redlining, which has reached a really wide audience. Very thankful for the audience that it's reached.

Dianne Harris:But I think we have to understand housing at every level we can possibly understand it. And if we're gonna really understand what has undergirded the ability for this country to very purposefully not see the ways housing discrimination has been enacted over decades and decades and decades of time. If we're gonna try to undo it in any way or advance conversations about fair housing.

Mabel O. Wilson:Well, thank you, Diane. I think this has been a really, incredible conversation, literally revisiting little white houses. So thank you for for the work, and and thank you for the, I think, this important contribution across so many fields. And I'm very excited that, you know, you know, more people are going to to be be reading it.

Dianne Harris:Thank you, Mabel. This has been such a pleasure and a delight as always, and I look forward to being in dialogue with you anytime I can possibly be in dialogue with you. So I learn from you every time we talk. So thank you so much for this. It's been great.

Dianne Harris:And thank you to the University of Minnesota Press for all they've done, with the book and for the second printing. Really, really glad that it'll be out there for a while.