Cinemal: Films and animals, majesty and mystery

Engagement with artistic practice and engagement with the natural world both require your full attention.

Giovani Aloi:This is Giovanni Aloi and this is a new podcast for the Art After Nature book series. At a time of unprecedented ecological crisis and cultural change, Art After Nature explores the epistemological questions that emerge from the expanding environmental consciousness of the humanities. Authors featured in this series engage with the recent ontological turn, appending anthropocentrism, in order to grapple with the dark ecological fluidity of nature cultures. The anthropogenic lens of inquiry emphasizes an ethical focus for grounding the modern human politics of our era. Within this framework, art theory, practice and criticism are reconfigured as intersecting platforms upon which current philosophical trajectories can be mapped.

Giovani Aloi:The series engages with the politics and contradictions of the Anthropocene in order to problematize recent and influential disciplines such as animal studies, posthumanism and speculative realism through art writing and art making. Our books, published in the Art After Nature series, fostered through multidisciplinary accessibility and diversity, and each volume aims to provide readers with the opportunity to creatively engage with new and alternative discourses at the intersection of art, science and philosophy.

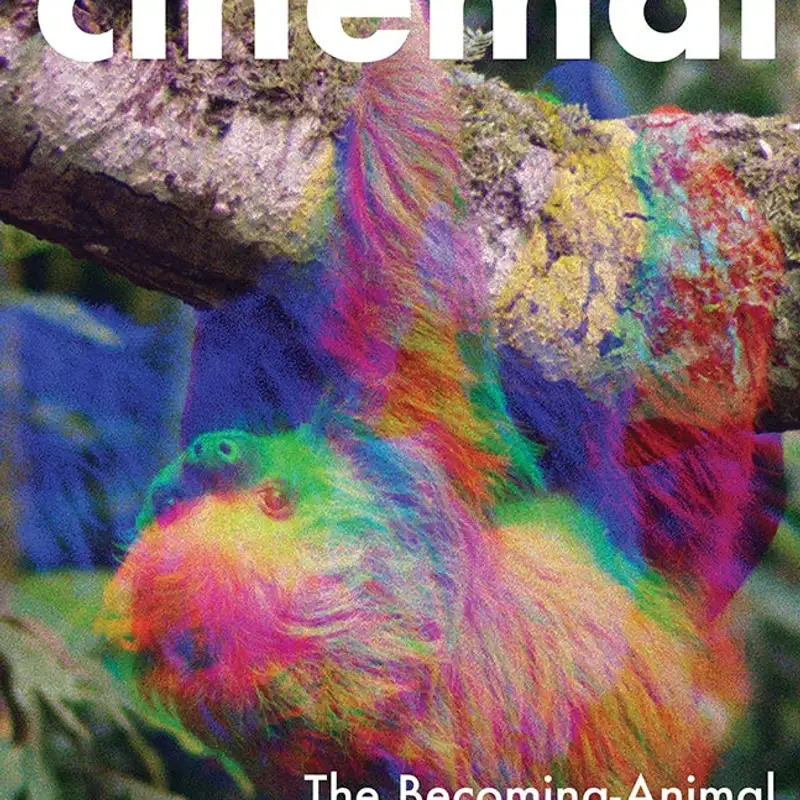

Caroline Picard:This is Caroline Picard and today we are here to discuss the latest book in our series, The Becoming Animal of Experimental Film by Tessa Laird. A foray through the wilds where experimental films and animals collide. Like the flash of a tropical bird's iridescent wing, cinema can be furtive and intensely beautiful and it can leave a viewer craving more. Cinnamal is Tessa Laird's passionate inquiry into the ways that films mimic the majesty, mystery, and movements of animals. Her field notes from countless hair raising encounters with films in their natural habitat.

Tessa Laird:Imagine this. You find a feline familiar under the veined velvet of taro leaves. She unfurls slowly like a tiger lily, her emblematic flower, orange and spotted as she is. You begin to understand that a familiar is your bridge to the world of animal magic, animal logic, animal language. Your familiar is all animals, not just those of her own species.

Tessa Laird:In this feline, you catch glimpses not just of yourself as you mirror each other, but of a host of nonhuman animals, including butterflies, majestic orange with black veins, the monarch, which is the tiger lily, if not the miniature tiger of the sky. Then again, when you apprehend her tiny bouquet of a face, you find it's not a cat, but an owl who gazes back at you with saucer shaped incredulous eyes, not to mention the mousy breath of the huntress. The cat I'm trying to conjure here was known to me as Kira, two thousand and two to 02/2019, and I share the images of her that run through the projector of my mind because she was and remains a lure for me toward animal becomings and ecological thinking. Keira was a flesh and fur feline, not a film, but I consider her a cinemal because in the metacinema of my mind, she's all montage, perpetually becoming other, leading me toward more capacious and relational ecologies. Her nervous glancing, her vibratory vigilance remind me of a meerkat on lookout duty.

Tessa Laird:Her tawny fur, sprightly gait, bushy red tail, and whiskery pointed features belong to the fox. Curled up, she's a snail with the speckled shell that gives her and her almost always female feline kin their name, tortoiseshell. What territory does the mottled map of her fur trace? She could even be reptilian with that party colored coat that mimics the scales of a diamondback in some lights, or a rattler who sleeps coiled, but when irritated, vibrates the tip of her tail in warning. When riled, she hisses like a snake and bares her fangs.

Tessa Laird:In the undergrowth of the garden, she's a sleek, stippled koi, a marriage of sunlight and shadow hiding under lotus leaves. She's also the spirit of the spotted leopard, a tiny tiger, or perhaps it's the tuftey faced cheetah she resembles most.

Giovani Aloi:Wonderful. Thank you so much, Tessa, for starting our podcast for the publication of your book Cinema with such a poetic passage. I couldn't help but think all the way through that this gives me so much more than Derrida ever gave me in The Animal That Therefore I Am and that fleeting appearance of a cat that flickers only momentarily into the flesh and fur that you mentioned to become a literary animal, perhaps far too quickly. I never have come to terms with how Derrida's cat became so emblematic and so powerful in animal studies and yet so void and so kind of missing the mark. So I don't know if this was your intention necessarily, but it really feels like you're making up for a massive animal studies shortcoming.

Giovani Aloi:Tell me how this came about and how may it relate to Derrida, if at all.

Tessa Laird:That's so interesting, Giovanni. I never actually thought about it that way, but I have thought about Derrida and his cat quite a lot. And I guess I was just being lured by the animal, and that's what I'm trying to do in the book. And I guess that's what Donna Haraway talks about when she sort of says Derrida missed his opportunity, you know, because he didn't actually connect to the animal or make an attempt to connect with the animal. That's what I've been trying to do both in life, but then once, you know, especially once the animal has gone from my life to process, you know, what was that?

Tessa Laird:What happened there? Who was that being? And what has she taught me? I dedicate the book both to Keira and to Corinne Cantrell, the Australian filmmaker who actually just passed away at the age of 96, and to Corinne's cat, Nim Nims, who I never met. She was long gone before I met Corinne, but she was also a tortoiseshell cat, and she was also still very much on Corinne's mind and in the films of the cantrells and in the paintings of their son, Ivor Cantrell.

Tessa Laird:And so it sort of felt like I felt like there was this triad, if you like, of influences, the cats, Corin, the filmmaker, and I felt that I had to sort of acknowledge them all three together as this kind of nexus of forces, if you like, forces of nature and forces of creativity.

Caroline Picard:There's a part in your book where you talk about Derrida's, I think the word is, philogocentrism. I don't know if I'm pronouncing it properly. And it's sort of like, I think you describe how you're building on that cat essay, but then also breaking from it. It's interesting to me that within this triad also of your work, you're addressing the animal, very attentive to language and wordplay, but then also incorporating cinema and film. I would love to hear you also talk more about how that stool, that three legged stool, emerged for you or how you thought about building it.

Tessa Laird:Well, guess I really have to acknowledge Derrida because he created the hybrid word animo. Although I've also heard that Elaine Sisu actually the first person who did that, but it's hybrid word that combines animal and mot, M O T, word in French. And this hybrid being is kind of like the animal in literature and the animal in philosophy, and it inhabits the texts. And it sort of is both trapped by those texts and enlivens those texts. And so I was kind of really intrigued by this figure that Derrida had created.

Tessa Laird:But at the same time, I was watching all these experimental films at the Cantrell's place where because they refuse to digitize their films, they insist that they be shown in their original format. So I was literally sitting in their basement watching these films on the original celluloid and at the same time reading animal studies texts and sort of thinking, how are these things related, if at all? And suddenly it came to me that there was this also hybrid being that inhabited the film, and that was I decided to call it cinema, which is, you know, sort of cinema with the animal tail, if you like, at the end. And as soon as I thought that, I sort of thought, well, it's not that I'm looking at animals on screen and thinking about cinematic animals, but I'm thinking about the film itself as a lively entity. Perhaps the film itself is an animal or becomes animal at some point.

Tessa Laird:And if so, how does that happen? And what what are the characteristics of the film that prompt me to compare it to animal characteristics? And I kind of made a little checklist in my mind, you know, when I see these kind of flashes of color that you might see, you know, in a bird, kind of performing some sort of dance or the peacock, you know, shaking its eye spots. It might be when there's an actual kind of rupture, like a scratch, perhaps a literal scratch on the film. It might be when there's kind of endless repetition and you think about, say, a birdsong where the same phrase is repeated over and over and over again, or it might be when there is a kind of, again, a rupture to that kind of repetition when there's a heart rending cry or something that sort of takes you outside of yourself.

Tessa Laird:So I had these thoughts when watching and experiencing film that there was some kind of becoming animal of the film, but then also, I suppose sympathetically of the viewer when experiencing that. And my hope in all of this is that by experiencing these kinds of artworks, we are brought back to ourselves and reintroduced to our own animal natures, and we kind of get away from this nature culture divide or human non human divide. And I think that what's most valuable about these kinds of films is that they bring us back to our own true natures in some way.

Giovani Aloi:Yes, absolutely. I think that's the part of the project that when you pitched it a few years ago now to Carolyn and I, really fascinated us. It was an interesting opportunity for me as well to reconnect a little with animal studies, which is a field that I haven't really felt very connected with over the past ten years. And I was wondering, I have, I think it's like two questions into one, is like, I would like to continue a trajectory that we've already taken related to language and the poetic language that you deploy so beautifully throughout the book. I think it's so great that not only you can navigate your theoretical frameworks and academic lenses with integrity and rigor.

Giovani Aloi:But you also have written a beautiful book that it's very enriching as a read. And there is something about the way you deploy language throughout that I think tries to accomplish something more than the average academic book that theoretically wants to pin down butterflies on a board tends to do. But there's also a question, I think, broader question related to animal studies. So I wanted to know how you see the book fitting into a broader scholarship of animal studies in terms of the trajectory that the field has taken over the past ten years and how this specific linguistic turn that you have decided to employ fits into that? To me, it's a little bit like a hopeful future model for animal studies.

Tessa Laird:Wow, that's high praise. I mean, for a start, I come from an art background. I went to art school. I spent a lot of time being an art critic. I'm always thinking about how I can write about something that is often nonverbal in a way which doesn't pin down the butterfly, as you just said, but actually kind of releases it into the world or even multiplies the butterflies.

Tessa Laird:I'm really concerned for my language to actually, maybe not just so much emulate the works that I'm talking about, but to be infused with some of their energy and beauty and power or even surprise. And in terms of what it can add to animal studies or what it does differently, I feel like there has to be a kind of a marriage of the ethics and the aesthetics. And, you know, that's what I'm sort of interested in. Guatari calls it, you know, the ethico aesthetic paradigm. And this idea that you can't really have a successful politics if you don't address issues of the sensory engagement with the world and some sort of joyous imperative.

Tessa Laird:Otherwise it's just gonna kind of fail. Nobody will want to come to your party. So for me it's really important that the writing enact the thing that practice what it preaches, if you like. And there's a few models there for me. One is that, Michael Taussig used the phrase four legged writing, which I love, and he uses it in contrast to what he calls agribusiness writing, which is kind of like the writing of academia, but it's also tied into this literal monoculture that's blanketing the planet.

Tessa Laird:There's that phrase that Vandana Shiva uses monocultures of the mind and it's kind of what's happening every time you're expected to explain something in academic jargon and completely forgetting about what language is and what language can do. Another model is Brian Masumi, in his book about what animals teach us about politics and elsewhere has talked about languages being the thing that the human animal excels at or expresses itself through, and that paradoxically language is where we can become animal. You know, we can find our animal selves in this tool that we wield, which is language. And it's a matter of doing that in an expressive way, which actually enhances our engagement with the world rather than pinning it down.

Caroline Picard:For some reason, it also makes me think a lot about movements, like in your opening passage about the cat, like part of why your cat becomes such an individual personality is because of the way you're using your writing. And then also there is nevertheless a way where your experience of the cat's strangeness, let's say, your language allows us to see how the cat slips into different emanations of other animals. You describe also how color is associated with movement. And so there is something very much alive about this presence, I guess, for lack of a better word.

Tessa Laird:Yeah, well, I guess movement and metamorphosis and transformation, they're all things I'm really interested in. A few things there. One is that New Zealand Modernist Artist Lin Lai is quite a force in the book, even though I tried to minimize it because I wanted it to be about contemporary artists. And he was born in 1901 and died in 1980. But he's still very much a part of it because I grew up in New Zealand.

Tessa Laird:I watched his films at art school. He was kind of a pioneer of scratch film and direct painted film directly on the celluloid, and he also made kinetic sculptures. He kind of said, you know, I want to make an art of movement, and I don't want to represent movement. I want my art to move. And so this is why he was really, attracted to kinetic and moving image as his sort of media.

Tessa Laird:But in addition to lie and movement, I'm sort of really interested in this idea of animism and animation, maybe literally in some cases. Eisenstein has lots of interesting things to say about Disney and what animation actually is, and, you know, he kind of surmises that it is the sort of, the remainder of of animism in our contemporary life. This is how it comes out. And I really wanted to not just talk about animals, but about lively forces in across the gamut of of of nature and cultures, and to think about the liveliness of all things, including so called inanimate things. And so there's also a chapter about spirits, for want of a better word, about the sixth sense and the unseen and the ineffable and how they might show up on screen.

Tessa Laird:And I feel like that's, again, like on a continuum. It's not as though there's a kind of a cutoff point between the spiritual and the material worlds, and especially not when you're looking at something like film. All of film is a kind of specter. There is a lot of scholarship about the animal specter, you know, especially a kira lipid. With that and with the kind of specter of animal death, it makes sense to also include the undead in the lively, if that makes sense.

Tessa Laird:So movement, transformation, and openness to fluctuating states was also something I was really interested in.

Giovani Aloi:And Tessa, I was thinking more broadly about questions related to representation, abstraction, realism, and how objectification or freedom from objectification might play in the context of those modalities. I was thinking about very early conversations about objectification and representation in the context of animal studies, like specifically Steve Baker and his consideration of becoming animal as an opportunity to free the animal from the objectification of classical representation and symbolism. So I was wondering how conceptions of cinema might play into that paradigm.

Tessa Laird:One of the things I found myself bucking against a little bit was the idea of realism, because personally I feel that I'm more interested in the kind of vocabulary of surrealism, which is not to say that I don't value documentary approaches, but I don't see that there's a way to truly represent the reality of the animal experience from a human perspective. And I think it's probably more valuable when we try to bridge the gap, if you like, between human and animal experience with a more kind of imaginative searching way of entering another person's or another being's sensorium, often very different to our own. So I guess what I appreciate is perhaps those moments when I'm not witnessing a representation of an animal but I'm perhaps witnessing a representation of reality as it might be experienced by that animal. Maybe I'll give an example. A very short film by the Cantrells called Articulated Image, which is a very rapid frame rate cut of movement over a pot plant on a stairwell and that's all it is.

Tessa Laird:But when watching that film I felt that I was inhabiting the body of a skink or a small lizard and don't ask me why but that's the kind of thing that came into my mind. It was the time signature signature and the frame rate of that film. That's what it did for me in a way which I don't think I would have felt had I been watching a kind of realistic documentary film about a lizard. And so I feel like there's something about using our filmic language and maybe our verbal language too, to inhabit the interiority of what it means to be animal rather than representing them from the outside. And I think that's one of the key takeaways of Deleuze and Guattari's concept of becoming animal.

Tessa Laird:It's very much against representation. And I feel that realism is still sort of falling into that trap of being a realism for humans. I would say a neurotypical humans at that. So I'm really interested in troubling, what do we get to call realism in the first place and who says so? That makes me think too about how, where the metaphor is

Caroline Picard:in a way. I don't know if you would agree with this, but it's almost as though by introducing cinema or film as the animal And you talk about the celluloid skin, for instance, and there's all these different the performance of color on screen and how it's sort of transportive. But it's interesting to imagine that if we are able to conceive of and fully consider film itself as a type of animal, then that might actually change the way we are capable of engaging with the otherness of animals more broadly.

Tessa Laird:Yes, absolutely. On metaphor, there's a wonderful word that Akira Lipit came up with, which is animetaphor. And it's another hybrid word and it's a kind of animal metaphor, but it's also anti metaphor. It's kind of like the embodying and the actualization of something rather than it's being a metaphor, which is something I'm very interested in. But at the same time, metaphors can be very seductive and juicy and I'm sure the book is absolutely riddled with them.

Tessa Laird:And I think maybe that's part of it too, which is the idea of being playful and being able to take things when you need them and want them and also problematize them at the same time. So I guess I've had my fun with metaphors at the same time as trying to prod myself and others to move beyond metaphor as well.

Giovani Aloi:What ethical dimensions do you think cinema brings to the map of animal studies for practitioners, for theorists, of course, given your sensitivity to language as well, but also I'm thinking representationally approaches that might be preferred in comparison to others based on your mapping.

Tessa Laird:The idea of attunement is quite important to me and having a sort of sympathetic resonance or vibration with animal life, which can't be purely theoretical and has to be somehow felt. So that the ethics, as I said, has to have a kind of aesthetic dimension and that's the way in which it becomes a lived reality rather than a kind of theorem. So that's, I think what I'm bringing to the table as a kind of reminder that engagement with artistic practice and engagement with the natural world both require your full attention and your full sensory engagement and commitment. It makes me think also about the various figures and voices and philosophers that you draw in. You have this wonderful, I want to

Caroline Picard:say like pantheon of presence, whether they are animals or films or philosophers. And I guess I wondered, because there is so much movement through, how you considered integrating everybody and bringing everybody to the table. And like, when did you know when to introduce certain figures? If that makes sense. Because they feel very handy.

Caroline Picard:They feel very, like, present to you because I think they occur, for lack of a better word, very naturally in the flow or the course of your writing. It seems to me that it might be difficult to choose from a writer's perspective when to call on one versus another.

Tessa Laird:I would say it's completely intuitive. There's absolutely no logic to it. The whole book has really grown out of an intuitive inquiry and some of it is happenstance as well. I mean, I didn't know anything about Baptiste Maurizot, but somebody sent me his book about tracking wolves and it became very important to my thinking. And there's appearances by people like Alexis Pauline Gumbs and her wonderful book, Undrowned, about marine mammals.

Tessa Laird:And these seem to me ways in which people are addressing animals directly. They clearly also come from very philosophical or very political backgrounds and the way that they've managed to weave animal encounters through their texts has been really inspiring and foundational for me. But also I talked to the artists themselves, the filmmakers themselves, because they embody such a wealth of knowledge. For example, the artist Shrewana Spong, I read her PhD and it really opened up for me not only how her films operate but how film in general operates. It was a very inspiring text for me.

Tessa Laird:So I feel that I'm led by the films themselves, but the films come with a whole raft of voices that they're drawing upon and that I can draw upon too. And of course, everything that I'm reading at the time feeds into that. Maybe it is kind of like actually making a montage sequence. It's sort of operating with all of these inputs, but finding a way, you know, in which you can make a rhythm or a pattern. And pattern I think is maybe one of the guiding principles of the whole book that there are these little refrains and repetitions that pop up here and there.

Tessa Laird:I see the whole thing as a kind of essay on dappled light. It's all about light and shadow and the recurrence of certain images and tropes.

Giovani Aloi:Since we're talking about the work as a writer, thinker, I was interested in learning more about your process and how the challenges that you faced in assembling all these voices and also works of art. You know, this type of book is complex to put together because of all these partners, collaborators, like virtual collaborators that come textually to keep you company and yet sometimes might want to stay longer than you expected. You have to negotiate space. Somebody becomes too prominent. There were also, I remember, moments in which we wanted to negotiate certain contemporary voices, perhaps more than other classical animal studies, voices during the round of reviews.

Giovani Aloi:So what were the challenges you faced into putting this together to make sure that it speaks to animal studies of today and beyond? I think it's a great the book is a great contribution to animal studies, because I see it as by far exceeding the field of animal studies itself. I think it reaches well beyond.

Tessa Laird:My biggest challenge is always how to stop trying to put everything in and that's kind of what I ended up doing anyway. But I absolutely hate getting rid of things. I always feel like it's cutting off an arm. You know when you're talking about relationality it's like well where does one thought end? It could go on and on and on.

Tessa Laird:So for me it's always about you know when to stop and what to get rid of and that's always hard And it's not for me difficult at all to see all these wonderful connections between things. They just come naturally. And so I feel probably looking back at it, there's probably still too much in the book. As you know, I could have gone into more depth, like I'm always telling my students, less breadth, more depth, but I myself can't practise what I preach. And I do so love the ways in which things connect.

Tessa Laird:But I had some good feedback along the way and there were many, many provocations. One of the earliest ones I remember, I thought was really interesting, was a Romance language speaker saying you can't call the book cinema because that means, you know, bad cinema and it has all these negative connotations. And I thought that's true but that's exactly how the animal's been portrayed for so long and that's how the animal often comes into film as some sort of malevolent entity. So I felt like I had to kind of run with it and reclaim that and say, well, there's a maul at the tail of every animal quite literally and we can't be running away from that, we have to embrace it. And there's been many, many moments where I've had to reconsider something and think about what it means for the book as a whole, but at the same time my default is to keep things and incorporate things and argue for their necessity rather than to leave them out altogether.

Tessa Laird:This makes me want

Caroline Picard:to go back to this idea that Giovanni brought up as a counterpoint of how often scholarship and scientific thought wants to like pin the butterfly and how that is set in contrast with the type of movement which is also as we've discussed your writing sort of exemplifies. So I guess I'm interested in how you think about or one thinks about the ethics of movement and aliveness in writing? Or like if you allow the aliveness of your subject, for lack of a better word, to come through in the writing, does your sense of ethics or scholarship also have to adapt?

Tessa Laird:I feel like the ethics is in the approach and they're indivisible. The method is a way of enacting the ethics and making it visible and live. I really don't believe you can argue for a relational view of the world without practicing that relationality in your writing because if you fall into a kind of academic jargon while you're trying to talk your way out of that worldview, it's not going to work. You have to walk the talk, which actually maybe that's what four legged writing is. It's the body coming into the text.

Tessa Laird:And then I hope the readers will take it to the next step, which is continuing with the walking metaphor. I mean, I don't want this to be an endpoint, you know, what happens to the reader after reading this text. Maybe they feel empowered or emboldened in their own creative practice or in their writing or even just in their relationships with the natural world, with animals, with how they experience light and shadow, dappled light through the leaves. Is that a cinematic experience? Maybe it is.

Tessa Laird:So I want there to be some kind of movement beyond the book as well, movement into the world. One of the

Caroline Picard:things you talk about in your book, Tessa, is how film as a medium is also kind of dying out. And you sort of compare it with animals, you know, during the sixth great extinction. And I was thinking about the digitization of film, but then also the pressure to AI optimize our language. That seems like another push towards monoculture, which is really interesting to me.

Tessa Laird:Absolutely. I guess I haven't mentioned anything about AI in the book and I've kind of resisted talking about things like virtual reality. And these are probably precisely the things, you know, that I should be addressing because this is what's happening right now. But at the same time, I feel like as we're charging into this new unknown with all these new technologies, we're really turning our back on technologies that we've had and they are like dying species. This was actually something that Corinne and Arthur Cantrell have talked about is that they were sort of the last handful of people using analog film at a time when video had completely taken over and they remained steadfast and true to their medium, but they felt like they were a dying species.

Tessa Laird:And now that Corinne has passed and there are some films and canisters that have not been digitized that may melt away with time, it's kind of scary to think about that, you know, at a time when we're in the sixth great extinction event as well, which is far more terrifying, the fact that we're losing species at a massive rate. But I feel like these things are somehow entwined. The fact that I don't think we have enough respect or care for true diversity and instead we seem hell bent on creating modes of turning knowledge and experience into a kind of vast arena of homogeneity and sameness and the reproduction of more and more of the same. And I'm really interested in the preservation of pockets of a true sort of singularity in resistance to that, you know, resisting the urge to pick things up just because they're new and because you think that you need to be like everybody else by utilizing these tools and instead celebrating what genuine diversity remains both in the natural world and in our artistic and literary production. Yeah, I think it's very important to fiercely safe safeguard what remains.

Giovani Aloi:I think this is a wonderful place to end our conversation. Thank you so much, Tessa, for joining us today. It's been a pleasure talking to you and we look forward to seeing cinema traveling across the world.

Tessa Laird:Thanks so much, Tessa. I really appreciate it. Thank you. Thank you both.