Christopher Isherwood’s California lectures: with James J. Berg, Chris Freeman, and Claude Summers

These lectures were essentially lost to history or filed away deep in an archive until you publish this book.

Claude Summers:My becoming interested in Isherwood really had to do with the fact that Ted and I saw so much of ourselves in A Single Man.

James J. Berg:Christopher Isherwood kept so much, and Don Bacardi kept it pristine that there's so much there.

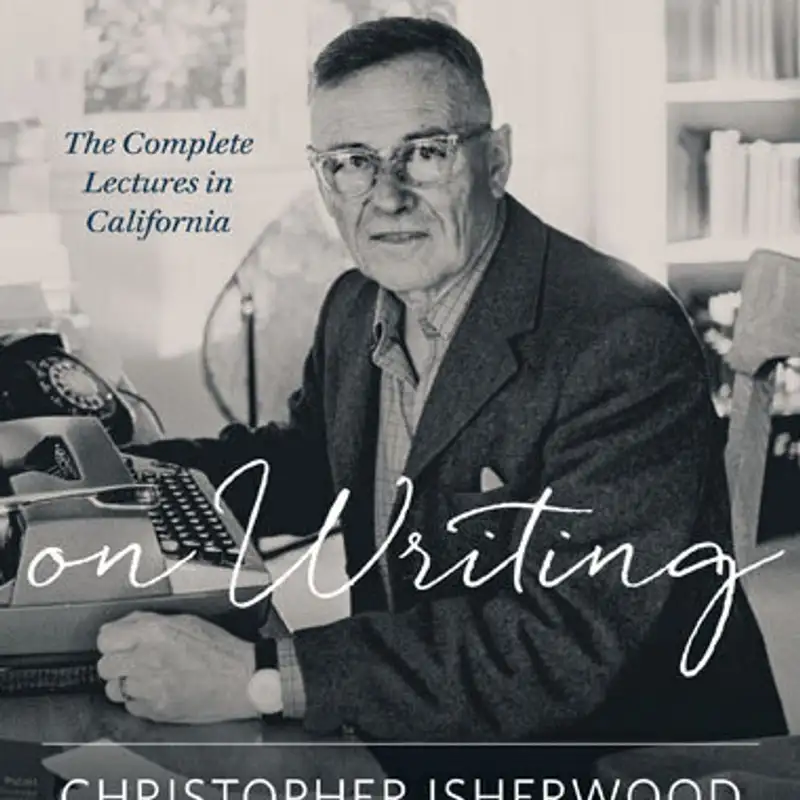

Chris Freeman:Hello, and welcome to our conversation about Christopher Isherwood on the occasion of the new and expanded edition of Isherwood on writing coming out this fall from the University of Minnesota Press edited by James Berg with a forward by Claude Summers. I'm Chris Freeman, and I'm here with both Jim and Claude to have a conversation about Christopher Isherwood, Isherwood on writing, and other exciting related issues. Jim Berg and I have been working on Christopher Isherwood for quite a long time. My best calculation is the same amount of time from the time that Christopher Isherwood moved to Los Angeles and then published Single Man, about twenty five years. And Claude Summers has been working on Isherwood, even longer than that.

Chris Freeman:Jim Berg is also a developmental editor who works with academic authors, helping them to bring their work to publication, and he and I have collaborated on several books about issue with including the issue with century, which won the Lambda Literary Award back in February. Claude Summers is Emeritus professor from University of Michigan Dearborn and is a real pioneer in gay and lesbian studies, although he started his work as a renaissance and seventeenth century scholar. But in the late seventies, he was working on Christopher Isherwood already and had, in fact, been one of the cofounders of the gay and lesbian caucus for the modern language association in the early nineteen seventies. And we'll be talking about that a little bit today because Isherwood was one of their first keynote speakers. So I wanna start, Jim, by asking you to tell us a little bit more about the Isherwood on writing book as an archival project and then what's new in this expanded edition.

James J. Berg:Okay. Great. Thanks, Chris. I first saw mention of Isherwood's lectures in the biography he wrote of his parents, Kathleen and Frank, which was published in the early nineteen seventies. As I say in the book, I marked that passage long before I wrote a word about Isherwood.

James J. Berg:Then when the Huntington Library in California acquired Isherwood's papers many years later, I was one of the lucky first scholars to see what was actually in the collection. And I found cassette tapes and transcripts of many of the lectures. I was awarded the first Christopher Ischwood Fellowship at the Huntington to research a project on the lectures and was given a grant from the Minnesota Humanities Commission to publish with University of Minnesota Press. Minnesota, at that time, had started publishing paperback editions of Isherwood's novels, and the director, Doug Armato, has done a great job of nurturing Isherwood's legacy and scholarship. So for this new edition, part of the interest is simply that this is the first time the book has been in paper, but it also includes some material that came to light after the original publication, including two lectures from 1965 at at the University of California Los Angeles in which he talks about a single man and a meeting by the river.

Chris Freeman:And, of course, now we recognize that a single man is arguably the most important book that Isherwood wrote. So having this new material really is, noteworthy.

James J. Berg:Yeah. And he, he talks a little bit about how the book came to be and what his intentions were for the book. And I think some of that is kind of surprising, even for those of us who have read A Single Man a number of times, they've read a lot of the scholarship about it. He tells a story that we've heard that you and I, Chris and Claude, you probably have heard before about how he started writing A Single Man and it was originally gonna be called The English Woman. Says he was recently very much taken with Willa Cather's work.

James J. Berg:To be specific, he says, my mortal enemy, a lost lady, the song of the lark, and the professor's house. And then he says, and in the way that one always longs to do something one can't, I thought how wonderful to write a very calm, sort of clear, uncomplicated, exceedingly simple story about a character, a single person and her life. And then he starts writing, an English woman and then changes focus to be about an English man, the George character as we know him now. And he talks about George as a person representing an almost laboratory specimen of middle age. He began to think what an interesting thing middle age is and how peculiar and how most people think it's a period of calm in a very beautiful, in a rather boring way as long as one doesn't have anything to do with it.

James J. Berg:When as a matter of fact, it's probably the most protean of all ages. That's to say part of the time when it's absolutely senile and at other moments monstrously juvenile. And it's a great age for committing indiscretions of all kinds. This came to me with considerable force because the night before, I'd happened in the middle of the night to go swimming in the ocean, which led to various situations which are neither here nor there. I love that that linking of his personal life to the the very famous and provocative scene of George swimming with his student Kenny in the ocean.

Chris Freeman:The ill advised swim in the ocean when he nearly drowns and or freezes to death because it's almost Christmas.

James J. Berg:Right.

Claude Summers:It it was an ill advised swim, but it was also, a baptism of the surf. And I think that that turns out to be well considered, in terms of what what happens afterwards. It is so marvelous to have these new comments that Isherwood made about a single band. Because as you say, we've come to see it as really Isherwood's masterpiece. And somehow, without this new material, that last lecture in the first edition cuts off so abruptly.

Claude Summers:And having the new edition just adds immeasurably to it. So, I am so happy that that that has been added to it.

James J. Berg:Yeah. It's so fascinating to hear him talk. And we'll share an audio clip later of him giving his what he called his last lecture. There are a couple of other points about a single man that he talks about that are pretty key to the book, but also key to the book's audience. Right?

James J. Berg:So he talks about his character, George, as a homosexual, which is pretty significant in 1964. And he talks about, you know, George being very involved in his own life as a middle aged man and to a certain degree, with the business of being And he uses the phrase other than the others, which you may recognize from the German days of the nineteen thirties. And he's very isolated from the others. And he goes on to say, that's why he's a homosexual. He's a foreigner and he also belongs to another kind of culture in some way.

James J. Berg:That's, of course, part of being a foreigner. He also has, by virtue of being homosexual, the added artistic advantage that even the death of the person that he was most attached to is sort of socially unacceptable. I mean, he can't have an accepted place in society even as a widower, so to speak. But on the other hand, he is in fact accepted by society and this is, of course, the paradox of social life and is even quite looked up to and is regarded as a sort of serious person and as a possible source of wisdom. I find his asides so fascinating sometimes.

James J. Berg:And he says, I still feel considerable satisfaction over this book, but perhaps that'll pass. And then the last thing that I'll share is about one of the major questions that's that readers have at the end of the book is whether, spoiler alert, George dies. And this is what he says. The book is written on a very familiar concept of a day equaling a lifetime. And in a certain sense, you have the ages of man all revealed in one.

James J. Berg:And since all life ends in death, there has to be a death included. Now some people have said it would have been much better to have had a symbolic death. But what I did in fact was to have a kind of optional death because I phrase this very carefully in such a way that I do not actually say that he actually died on that particular night or even that he was going to die. And I think that's the most we have from Isherwood at this time, about what is, as we've said, his most significant work perhaps and especially his most significant American work.

Chris Freeman:And for me, this comes down to the different levels of what we know about Christopher Isherwood. We know from the lectures certain things. And, Jim, these lectures were essentially lost to history or filed away deep in an archive until you publish this book. So to me, they're absolutely essential lens into Isherwood's kind of theories of writing, but also he talks a lot about what he has read, his approach to reading. He talks a little bit about politics, being a member of the ACLU, and things like that.

Chris Freeman:And, of course, he does not talk a lot about being gay. And, you know, another place where we know so much about Isherwood that we didn't know, you know, a few years ago from the archive is from his diaries. So for example, in the, lectures, he doesn't really talk much about Virginia Woolf, but we know from the diaries that missus Dalloway was a key, source or inspiration, I guess you could say. Claude, you've been working on Isherwood since the late nineteen seventies, and we knew almost nothing about him except what he had published and a few interviews. So how is it for you to look back and think about when you first wrote you wrote a monograph on him that was published around 1980.

Chris Freeman:Isherwood was still alive. So how is it for you to think about how much more we know now than we knew then?

Claude Summers:I mean, we obviously know much, much more, thankfully, to writing on Isherwood, among other things. But I was very fortunate in that my late husband who died, just a year ago, so still pretty raw. But, he had corresponded with Isherwood when we first met in the nineteen sixties. And on several occasions, we then were invited to visit Chris and Don in Santa Monica One Year after I think it would have been 1972 after the MLA, which was held in San Francisco, we came down. And, of course, they were charming, charming people, and Isha would talk so freely about himself, that we were really sort of surprised.

Claude Summers:Although at the time I was writing the book, there wasn't as much nearly as much scholarship as there is now. There had been a book by Alan Wild, which was a very good book. I mean, it still is a very good book. There was Carolyn Heilbron's little writers and their work pamphlet, which which was good. What I found so interesting about working on Isherwood is that it was the first time I had worked on a living writer.

Claude Summers:So I was aware that there were, in some ways, it's much easier to write about a dead writer because they can't, they're not gonna say anything about it. It was interesting that issue would, he was scrupulous about not wanting to say anything that would influence any of my writing about him. And at one point while I was writing about it, I had mentioned, something about a character in Goodbye to Berlin. And I'd sent him a copy of that, and he wrote back. He says, well, this is all very good, but, that character was dead.

Claude Summers:And I said, no. And I think he had confused what he had written to what he had experienced in Berlin. And I I thought, well, that's interesting. He, I think it was Bernard or or the person who's referred to as the communist party leader in goodbye to Berlin. So, anyway, I enjoyed that kind of interaction with him, which, of course, would not have been possible with my with Christopher Marlowe, whom I worked on at at the beginning of my career.

Claude Summers:But it was true, and I and Jim makes the point in his in the introduction about how unsettled Isherwood's reputation was there. There was still a lot of resentment from British writers about Isherwood and Auden, and, and he hadn't gotten the kind of of scholarly, investigation that that he deserved. That was just beginning, and I'm just so happy that I was in on that. Although my my becoming interested in issue would really had to do with the fact that it, it was an act of love. Ted and I saw so much of ourselves in A Single Man that that, is really why I wanted to to write the book.

Claude Summers:But in any case, I was aware, you know, obviously, that that issue would was becoming by the way, something about the book that I think is interesting or the reception of the book was that it sold very, very well in hardback. So cheap hardback as they were then, maybe $10, but it sold very, very well. And Unger, thought that that was going to be a harbinger that it would sell much better in paperback. So they issued a paperback right away, but it did not sell well in paperback. And I think the reason for that is that Isherwood, at that point, was more of a cult figure.

Claude Summers:He had devoted followers who were gonna buy the hardback, but there wasn't as much of the residuals after that because the the hardback fulfilled the need then. So I I thought that said something about his status at the time that he had people who probably many of the people who came to the lectures who would've bought anything about Isherwood, who really wanted to know about him, but it wasn't gonna extend too much away from that them. The other thing about, Isherwood was that he had not received the kind of attention that I was hoping to provide at that point. Alan Wiles' book was so good, but it it was marketed exclusively to an academic audience, whereas my book was, also, marketed to a more general audience.

Chris Freeman:Claude, can you tell us about reading Single Man for the first time? That was such a landmark book in retrospect.

Claude Summers:It was a landmark book in my life too because, as I mentioned, my, late husband, Ted, we had just moved in together in 1963. And as I said, he he had so many Isherwood books, including the Auden Isherwood plays and the travel book and, things like that. I had just finished my freshman year. Ted was a graduate student. I just finished my freshman year, and I I had read, Goodbye to Berlin.

Claude Summers:I think that was the only, novel of his I had read. But we had heard in '64 of the publication of A Single Man, and we were so eager to get it that we actually read alternating passages to each other because we wanted to to end it at the same time. That was just an extraordinary experience for us, I think, and we always actually, when we got married, part of the ceremony was a reference to two passages, from a single man, the passage about Mrs. Trump and, and and the other passage about that that thing about the two of them together, each absorbed in their books, but always aware of their presence.

Chris Freeman:And so I think that gets me to one thing I wanted to ask you about from your forward, Claude, to Isherwood on writing, which is you talk about the difficulties of the gay movement, right, and and its public perception, especially, the unspoken assumption in the early sixties that homosexuality was not a topic to be mentioned in polite society. And I think we see that in the lectures still. And I believe in the excerpt that Jim is going to share with us in a moment, we'll get a little tiny bit of a glimpse of that. But can you take us into your thinking about talking about homosexuality in the sixties? Issuerood didn't publicly come out until Kathleen and Frank, which was published in '71.

Chris Freeman:So ten years earlier is when he's giving these lectures.

Claude Summers:That is the great paradox. On the one hand, it was an absolute open secret about Ishu and being gay because he wrote about it so often. And he wrote about it very differently from other writers, you know, even all the conspirators or the memorial or goodbye to Berlin or the last of mister Norris. He had different ways of approaching them, but they were not sensationalistic. You know, it was sort of comic in The Last of Mister Norris.

Claude Summers:It was not associated with the, quote, Christopher Isherwood character, but readers certainly would have known that his interest in homosexuality was quite different from most writers. But at the same time, he could not speak openly about it in relation to himself in these lectures, partly because, homosexuality was such a a fraught topic at the time. I mean, you know, Ted and I was at were as open as as we could be, and all of our friends in the literary circles we we were involved in knew that we were gay. And we knew that they knew that we were gay, But it would have been considered impolite for them to make that assumption clear that we really only talked about being gay with other gay people at the time. That gradually was breaking down.

Claude Summers:But at the time, we were using some of the same, euphemisms and so forth that Isherwood uses in his in his lectures, you know, talked a lot about individualism, talked a lot about, nonconformity. But they were really coded words for ways of talking about, homosexuality.

Chris Freeman:And you're talking about your friend. Right? Your friend.

Claude Summers:Exactly. My friend, Don McCarty, has has issue with says says at one point in the lectures. And and it wasn't simply I mean, there were real consequences too we need to remember. I mean, people you could get fired from even a university professorship. You could get fired for all sorts of of ways.

Claude Summers:Gay people were really under attack, especially in the fifties and very early sixties. Things got better in that decade, and luckily, it was able to culminate for Chris in being able to write in 1971 and Kathleen and Frank that, that he was gay. But those were difficult days to to to speak openly. And as I think I said in the foreword, homosexuality is so important to his work that you have to talk about it. But he talked about it in these roundabout ways until finally at I and I think the the passage that, Jim's going to play that he he somehow is freed at last.

Chris Freeman:Right. Well, you know, it's interesting. When I teach single man to, you know, undergraduates at the University of Southern California, one of the things I asked them is, do you think Kenny knows that George is gay? Do you think George's coworkers and colleagues know that George is gay? I kind of think probably not, actually.

Chris Freeman:You know, like, the secretary's in the English department or whatever. You know, he would want them to think he's a bachelor Englishman, and Kenny's just very curious about George's life.

James J. Berg:Right. And being an Englishman is enough of a othering for him in his own life that he passes under that umbrella of eccentricity. Right?

Chris Freeman:Yep. That's right. Exactly.

Claude Summers:And in addition, I think this Englishness is very interesting because there there used to be a joke. You know? He's not gay. He's just English. And that allows, someone like George to be eccentric, and people don't necessarily think that he's gay.

Chris Freeman:Very British. So, Jim, why don't you, set up for us, especially the context of this, audio clip that you're gonna share with us from one of the lectures. It's so great that we have some recordings, you know, because it really takes us into the room.

James J. Berg:Yeah. And his voice is so distinctive and, you know, and so so very British and eccentric.

Chris Freeman:And he's such a good speaker.

James J. Berg:He's a he's a really good speaker when he has, you know, planned remarks. And this is, an example of one of his planned, talks. So this is Christopher Isherwood delivering the honors convocation at the University of Southern California in 1974. It's very close to the transcript that we published in Ishiwad on writing called The Last Lecture. And by the time he gives this talk, he's working on Christopher and his kind and his retelling of his life in England and Germany in the nineteen thirties.

James J. Berg:And so this is after he's come out in Kathleen and Frank a little bit before he gives his famous talk to the Modern Language Association. He begins by talking about how he sees writers as outsiders, and that's a pretty prevalent theme in the lectures overall. And then he says that being an outsider is not the same as being a minority. And then he goes on to claim, membership in a minority group, and he says he is a homosexual.

Christopher Isherwood:Doctor Greenlee, ladies and gentlemen, the title of my, remarks this evening is my last lecture. A long time ago in 1961 when I was teaching at Santa Barbara, One of my colleagues, Doctor. Douwe Sturman, had the idea that everybody from time to time should give a last lecture. That is to say, the last remarks that he would make if he knew that this was the last lecture. I've never given this lecture since that time, and what I'm going to say tonight will be quite different, but I did try to do it at the Librero Theatre sometime in 1961.

Christopher Isherwood:Of course, if one goes on doing it, it becomes a form of Russian Roulette. And finally, it is the last lecture. I don't know how much, often tonight I'm going to try it. Quite obviously a last lecture should be short, and, it should be a sort of report on experience, that this particular individual has had of life, life, and so I'll try to run through a whole lot of things that occurred to me, in a kind of scrambled order. Of course, as a writer, I am like other writers to some, obviously to greater or less degree, an outsider in the sense that one withdraws, as it were, from a sense of community while one is actually doing the writing and the the kind of focusing on the on the material, whatever it is.

Christopher Isherwood:And in this sense, one always feels, when one's writing, and this of course applies to the other arts, that one is not trying to be folksy. One is not trying to say what the other people want you to say. One is trying to say the most individual thing you can possibly think of to say, because if you don't do that, you will not give anything that is the least original. Your only hope is to be, as personal as possible. What stuns you after saying some of these things is that people write to you and say, how did you know that about me?

Christopher Isherwood:And you find out that what you thought was your innermost secret is actually something that an enormous number of people share with you, which is reassuring. Being an outsider in this sense, however, is not the same at all as being being a member of a minority. It so happens that I belong to one of the minorities, the least popular one. I'm a homosexual, and, I've, of course had to face up to this situation throughout my whole life, and have thought about it a good deal. But what I'm going to say applies to all minorities, more or less.

Christopher Isherwood:The great thing that keeps occurring to me again and again is this, we members of any minority, of course, are fighting for legal rights of some kind. We want to have less discrimination against us in one way or another, and that's perfectly legitimate in my opinion. However, I sometimes think that we really legitimate in my opinion. However, I sometimes think that we really should not try, we really should not expect, everybody to love us. I think it would be very much better if, one understood that there are people who simply don't like you.

Christopher Isherwood:They have a prejudice. Now, of course, in a one to one relationship you can overcome that, but in general I think one should relax about it because I would very much rather that people voice their prejudice in a kind of verbal way behind one's back than they arrive one day drag you out of the house and take you to a concentration camp. So, the other thing which is also, distressing to me, but is true, is that the minorities do tend to be in competition with each other, and this sometimes prevents us from being from pulling together as much as we should.

James J. Berg:That's the last lecture, the first few minutes of it.

Chris Freeman:And he first gave that in 1961. That's the thing that kinda blows my mind because these are the issues that in 1962 when he was writing Single Man I think we know from the diaries, he started Single Man around February of nineteen sixty two. He allows George, especially in the classroom, but also in the highway driving scene, to voice these thoughts about minorities and majorities, about competition, about, you know, what would later be coalition building. That, of course, is the key to any kind of minority rights movement is you have to have more numbers and more support. So it's fascinating that he was thinking at a very sophisticated and ahead of his time kind of way.

Chris Freeman:Claude, does that strike you? You lived through these times. Does that strike you also when you hear those kind of remarks of being ahead of his time?

Claude Summers:Well, I do, but I I don't think he gave this last lecture in '61 or '2. I think isn't this from about '72?

James J. Berg:This recording is from '74.

Chris Freeman:This would be new material, Jim, for the earlier version. Right? So this is Right. This is not the text from '61. This is the text from '74.

James J. Berg:Right. And this points up, you know, very clearly what Claude talks about in the preface about Ishwad hanging back from saying things openly to his audience in his first iteration of these lectures. And then finally coming around to saying it openly and talking about it openly, in the nineteen seventies after he's come out in print and after he's, you know, been working on Christopher and his Kind, which is gonna be a big a really big splash. You know, and what he said, it comes back to what I said at the very beginning of our conversation here. He wrote in Kathleen and Frank that these talks he gave were practice runs for the real true autobiographies that he was going to write in the late sixties and early seventies.

James J. Berg:So, what became, Kathleen and Frank, Christopher and his kind, and my guru and his disciple. He's working through in the lectures the issues that he brings up in those, autobiographies.

Chris Freeman:Right. And he can, I guess, talk about those things in fiction in single man, but he's not really ready to talk about them in nonfiction as himself at that time? Jim, just looking at the table of contents for issue wood on writing, part one is called a writer and his world. So that was that series of speeches talks. The second part is the autobiography of my books.

Chris Freeman:So it is kind of part of the important sequence of Isherwood's self revelations. Claude, does that make sense to you to think of it that way?

Claude Summers:Absolutely. I think you're exactly right. The time had caught up with issue or or the the time had changed enough by the nineteen seventies with, Stonewall. Suddenly, the gay movement was not just a fringe movement. It was a little more mainstream.

Claude Summers:It's also, attracting a lot of pushback as well. But by the seventies, the world had changed enough that that Isherwood was able to be more open. And he, I think, came to relish his role as a kind of courage teacher, as this figure who who wasn't particularly interested, I think, in policy or things like that. But he knew that he had a role to play, and he was happy to do it. This wonderful passage that we just heard seems to me to be the doing that.

Claude Summers:You know, I think this is a very important evolution in Isherwood's life and in his works because he is thinking in terms of Christopher and his kind as well. That was one of the things when he addressed the MLA in the next year in in '75. I don't remember exactly what he said, and I hope somehow that lecture is has been preserved somewhere. But it was very similar to that. And he was courageous.

Claude Summers:He was funny. He was a person who had reached the point where he felt he could say what he wanted to say. That is the plenary address he gave at the MLA that year. It was very important to the gay and lesbian caucus, and he had reached a point where his his reputation was such that we were able to convince the MLA that that he should be invited to speak about his work. He he was doing on a larger stage what he had done, at the convocation at at USC.

James J. Berg:Yeah. He makes a joke in one an interview, about his talk at the MLA. The interviewer says something about how significant his talk was, and he suggests that the talk itself wasn't so significant. It was that the MLA had sat still for it.

Claude Summers:Well, they they did more than sit still.

James J. Berg:I mean, I think that's one of the benefits of the talks is that you hear him in a way where he's so very self deprecating and just sort of deflecting praise and deflecting his own. And and we know from his diaries that he has a very solid understanding of his own identity, of his own worth, and he he doesn't have any kind of insecurity in that way in terms of the quality of his work, but in public. And he just is so self deprecating. But the other thing that I wanted to say about that clip is just that chilling, chilling line about being woken up in the middle of the night and put into a concentration camp. This is something that he knows quite well from his own, life in Germany before the Nazis came and had the rise of the Nazis.

James J. Berg:And it's only about thirty or thirty five years before this is exactly what Jews and gays were experiencing in Berlin and throughout Europe.

Chris Freeman:Why he left?

James J. Berg:Right. And his own lover, Heinz, was arrested and put in a concentration camp. And it wasn't until Christopher and his kind that he wrote directly about it. Remember, he wrote about it in a fictional way and gave it to another character in down there on a visit. In a male female couple where the yeah.

James J. Berg:Voldemort comes to, England is turned away, and that is directly out of his experience with Heinz and is told from a memoir perspective in Christopher and his kind. And it's just such a, horrifying echo of the kind of rhetoric that we're hearing today in The United States about LGBTQ people and how the Christian right in this country have been attacking us, in so many states and in so many ways.

Chris Freeman:It's interesting what he says about people having prejudice and that not everybody's going to like you, especially in the context of what, you know, people refer to as cancel culture these days. I think there's so much that's far reaching in these lectures. And, again, for me, the great value of these lectures is that they're not the same as the diaries. They're not the same as the nonfiction. So it really is heretofore mostly unknown information, and it's very rare to get information on a writer who died, what, forty years ago to get this kind of treasure trove of material.

Chris Freeman:It's a tribute to, you know, Don Bacardi and the Issue Wood Foundation and the Huntington for this incredible archive that we still, I feel like, have not mined for all the treasure that's in it. Jim, do you wanna give us a couple of just closing thoughts about working in the archive and sort of what you are most proud of or think is most significant about issue with on writing and especially this new expanded edition?

James J. Berg:Well, working in archives is something that you don't get a lot of training in in graduate school, at least you and I didn't. And one of the things that you find is that it's just good fun. And you find stuff in it that you weren't looking for, that you were looking for. It's what a friend of mine once referred to as the paradox of shopping. Research is an activity which may or may not result in any findings.

James J. Berg:So the fun of it is there. And you're right, the archive, because Christopher Isherwood kept so much and Don Bacardi kept it pristine, that there's so much there. What I found I found stuff that was very, very fragile like cassette tapes. Remember them? That had been sitting, you know, in a file in a box in Santa Monica with the salt air for decades and was able through, a grant to preserve some of those on CDs.

James J. Berg:Remember CDs? That's the kind of stuff that it seemed like nobody had seen since the archive was turned over to the Huntington. It's such a wealth of material, and the best thing about it was finding Isherwood's own words, either in prints or on tape, and helping to bring those to a broader public. And Isherwood on Writing has had a really strong record of sales, in libraries and around the country. And I think this new paperback edition is gonna really do well.

James J. Berg:But I also wanna give a shout out to somebody I didn't know at the time who found in the archive after I had thought I put this piece to bed that had found this material. And as Claude pointed out, the lecture ends so abruptly that you just figured there was another page at least somewhere. And I think it had been misfiled or hadn't yet been filed or sorted when I was there. And so it points out that particularly for humanities scholars that there is a community of scholarship and that we benefit more from cooperation and collaboration than we do from working, by ourselves even if the image of the humanities scholar is by yourself in a library with a book. But there's definitely more value and more fun, I think, to the work if you're doing it with somebody that you trust and you can bounce ideas off of and who can find stuff that you didn't find.

Chris Freeman:We've certainly had that experience over a few books ourselves, haven't we, Jim?

James J. Berg:Over a couple of decades.

Chris Freeman:Yes. Indeed. Well, I want to thank Claude Summers for giving us his time from New Orleans this morning, afternoon, I guess, for him. And, Jim, it's always wonderful to hear you talk about your work on Isherwood, our work together, but also I'm so proud of you for this. It's such an important book, and I think this new material really does bring us even closer to single man as the singular accomplishment that it is.

Chris Freeman:So it's great that the University of Minnesota is supporting you to bring out this new material and to bring it out in paper, and I think maybe as an ebook also, I hope. So I think that's it for us. Thank you, Claude. Thank you, Jim. Thank you, University of Minnesota Press.

Chris Freeman:Thank

Christopher Isherwood:you.